| Part 1 of this saga is here. | Part 8 of this saga is here. |

| Part 2 of this saga is here. | Part 9 of this saga is here. |

| Part 3 of this saga is here. | Part 10 of this saga is here. |

| Part 4 of this saga is here. | Part 11 of this saga is here. |

| Part 5 of this saga is here. | Part 12 of this saga is here. |

| Part 6 of this saga is here. | Part 13 of this saga is here. |

| Part 7 of this saga is here. |

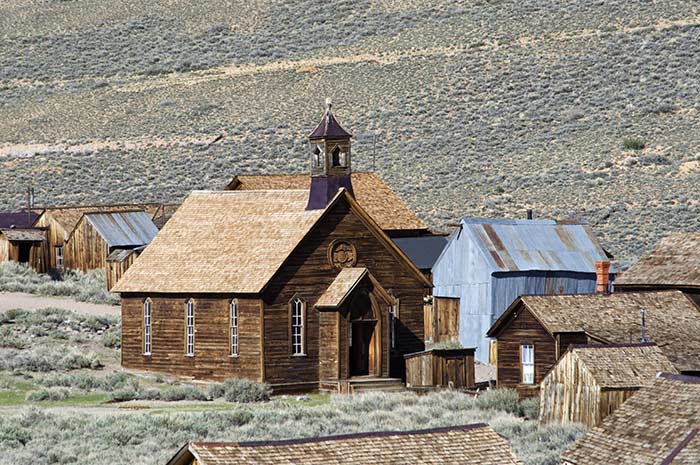

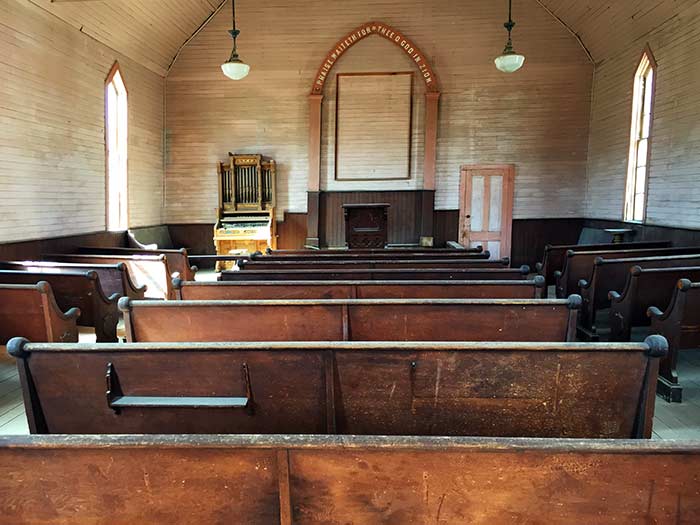

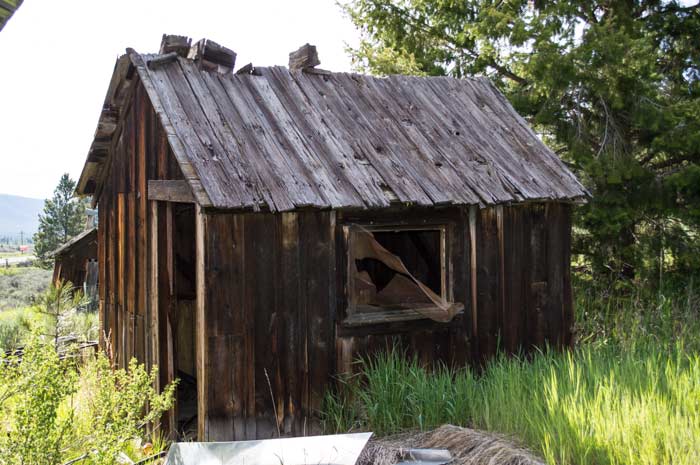

Bodie, California was a Victorian-era gold mining town high in the mountains between California and Nevada. The Victorians weren’t very big on human rights, or treating workers well, or sex, or just about anything else, but there is one thing they liked very much, and that was technology.

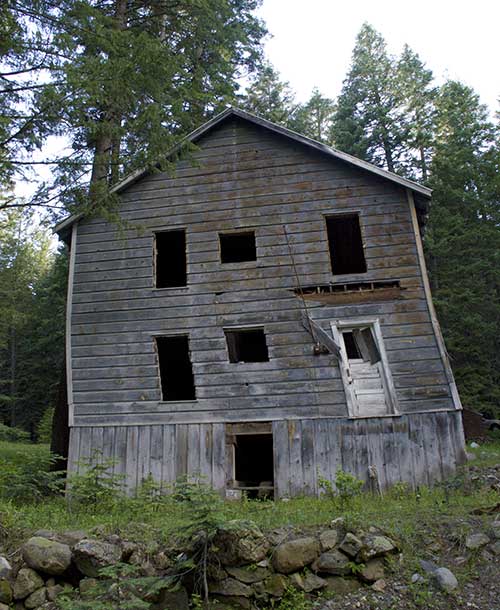

At some point, today’s cutting-edge tech will look as hopelessly antiquated as the detritus littering the ruins of Bodie. But tech always starts somewhere, and the Victorians were all for embracing the bleeding edge, especially where it making money.

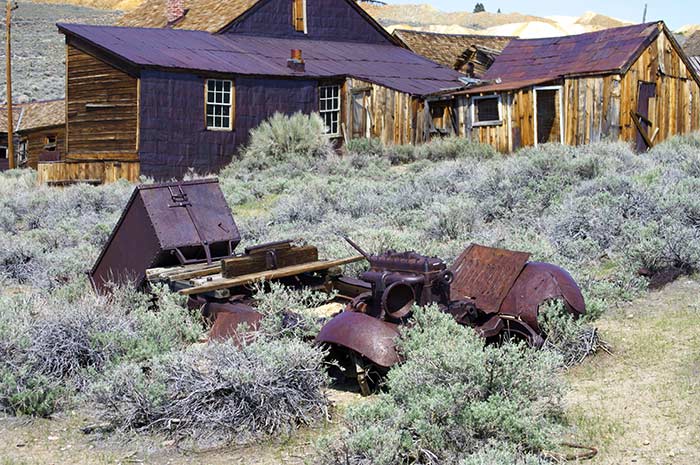

One of the many places Bodie kept up with the state of the art was transportation. When the town was founded, horses and stagecoaches were the order of the day, but that changed as the automotive arts gained ground. Today, the ruins of ancient cars lie scattered all over what’s left of the town.

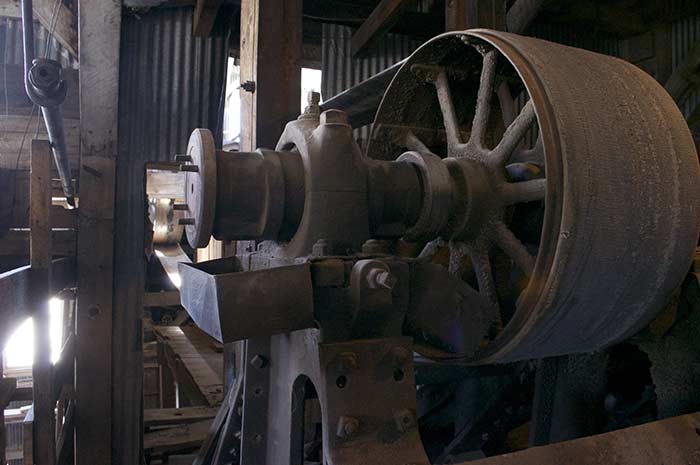

The residents of Bodie were willing to adopt any new technology that offered to make their lives better or, more to the point, more productive. They may not have had a sewer system, they may have dug their wells directly downstream of their outhouses, but they were on top of mechanization as soon as it was out of beta.

And the trend of abandoning old tech where it lay and replacing it with new didn’t end with mining or stamping machines. The derelict wrecks rusting quietly into the hills span years of the automaker’s art.

They also used whatever worked. In the winter, snow in Bodie could get two stories deep. If that made it most practical to let the horseless carriages get buried and break out the sleds in winter, that’s what they did.

Some of the abandoned cars look personal; others look like working vehicles.

There’s a certain sleek beauty to the lines of this one, I think.

Compare that to the severe utilitarianism of this (possibly horse-drawn?) ore cart.

But they weren’t technofetishists. Their approach to technology was relentlessly, brutally practical. If it worked, they used it. As many of the vehicles dotted about Bodie are old tech as new.

This is a different relationship to technology than many of us have today. They wanted things that worked, not things that were new. If it helped them get gold out of the ground, they used it, and that was that. It’s hard to imagine that utilitarian a mindset today. “New iPhone? Why? My phone makes calls just fine.”

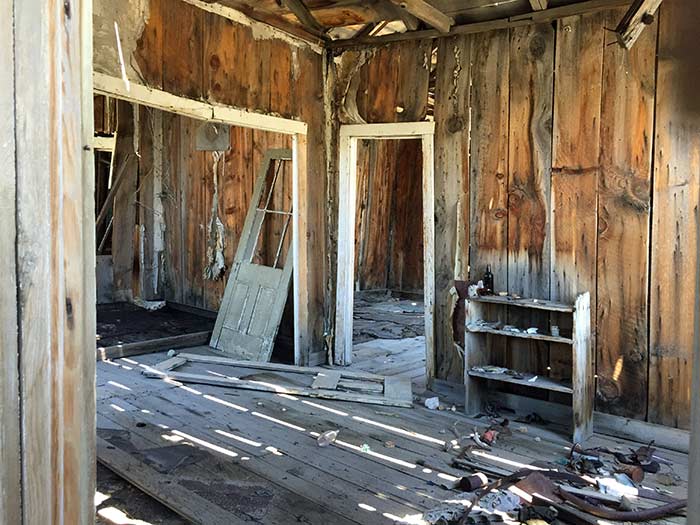

One of the creepiest and most splendid things about Bodie is the fact that when the gold left, so did the people, sometimes with such abruption it seems as thought they forgot to pack.

In reality, it’s more like they didn’t bother to pack. It’s difficult to get up and down the mountain even today; in a time when the only way in our out was by stagecoach (on a toll road!), there would be little incentive to take anything with you that could easily be replaced when you got wherever you were going.

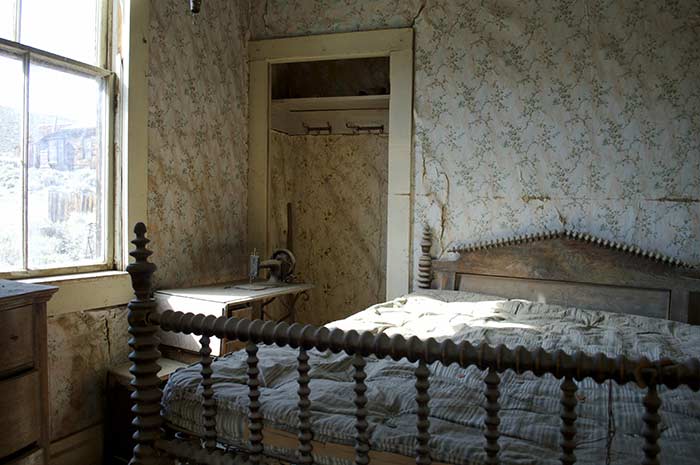

So the buildings in Bodie have rooms that look like their owners stepped out a half-century ago to pop on down to the store for milk and eggs, and never came back. It’s both unsettling and marvelous.

The cast-off child’s toy in this room is a reminder that people raised their kids here, in this inhospitable mining town with its brutal heat and bitter cold and chimneys belching mercury fumes.

Bodie had its own post office, which doubled as the postman’s living quarters.

This was someone’s home. Someone cooked meals here, sang songs here, experienced joy and sorrow here, lived here.

It’s hard to forget that countless lives played out here, from beginning to end. These people lived in an inhospitable place, in a different time, but they lived here, and they experienced the same range of feelings that you and I feel.

This was, first and foremost, a working town. The town had a blacksmith. Apparently, according to the tour guide, this was it. I have no idea what those things on the table are.

The general store looks very much like it did when the town was at its peak, at least if you ignore the film of dust that has fallen like a funeral shroud over it all.

I bet the aspirin was a guaranteed best seller.

The plaster bandages too, I reckon. Industrial accidents in the stamping mill were horrifying.

The Bodie Hotel is one of the best-preserved buildings still remaining. The sign says “meals at all hours,” and I believe it. This place probably never slept.

This room still has a bunch of toys, long abandoned, and what looks like it might be a proto-skateboard of some description.

I wonder if the child these belonged to was sad to give them up.

This room looks expensive to me.

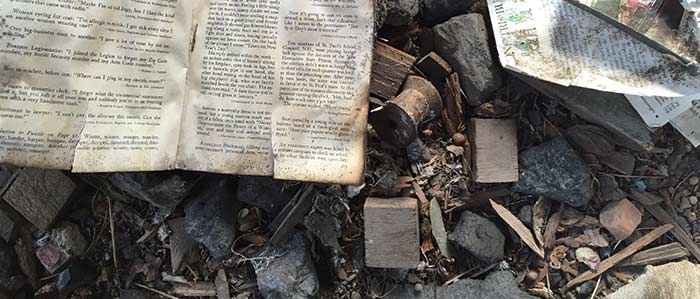

The headline is less interesting to me than the article beneath it: “Blast at magnesium plant injures 22.” There are people today who want to abolish OSHA. How short our memories are.

Bodie at its peak was home to many, many taverns. Today only one remains.

Next door to the sole remaining tavern is a gym. And you want to know something freaky? The cabin where Eve and I wrote More Than Two has that exact same model of hob.

Seriously. The exact same model. Check this out:

Freaky!

One of the guides explained that this was a “buggy,” as opposed to a “stagecoach.” There’s a big difference, apparently (and in fact the toll road into town had different tolls for buggies, wagons, coaches, and freight wagons).

We left Bodie as the sun grew low, and headed out to…well, that is a story for next time.