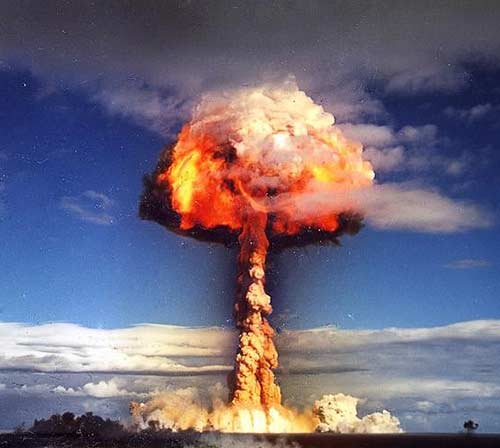

When all the world’s armies are assembled in the valley that surrounds Mount Megiddo they will be staging a resistance front against the advancing armies of the Chinese. It will be the world’s worst nightmare – nuclear holocaust at its worst. A full-out nuclear bombardment between the armies of the Antichrist’s and the Kings of the East.

It is during this nuclear confrontation that a strange sight from the sky will catch their attention. The Antichrist’s armies will begin their defense in the Jezreel Valley in which the hill of Megiddo is located. […] At the height of their nuclear assault on the advancing armies something strange will happen.

Jesus predicted the suddenness of His return. He said, “For just as lightening comes from the east, and flashes even to the west, so shall the coming of the Son of Man be” (Matt. 24:27). And again He said, “…and then the sign of the Son of Man will appear in the sky, and then all the tribes of the earth shall mourn, and they will see the Son of Man coming in the clouds of heaven with power and great glory” (Matt. 24:30).

–Sherry Shriner Live

Believers must be active in helping to fulfill certain biblical conditions necessary to usher in the return of Christ. Key to this plan is for Gentiles to help accomplish God’s purpose for the Jews. […] Jesus is saying that His Second Coming will not take place until there is a Jewish population in Jerusalem who will welcome Him with all of their hearts.

— Johannes Facius, Hastening the Coming of the Messiah: Your Role in Fulfilling Prophecy

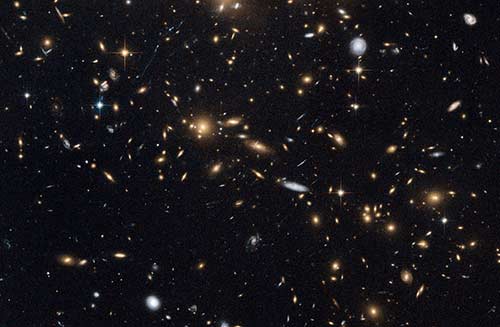

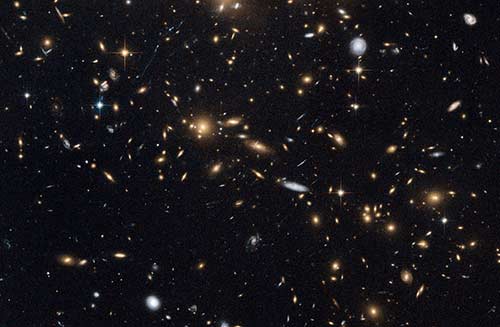

There is a problem in astronomy, commonly referred to as the Fermi paradox. In a nutshell, the problem is, where is everyone?

Life seems to be tenacious and ubiquitous. Wherever we look here on earth, we see life–even in the most inhospitable of places. The stuff seems downright determined to exist. When combined with the observation that the number of planetary systems throughout the universe seems much greater than even the most optimistic projections of, say, thirty years ago, it really seems quite likely that life exists out there somewhere. In fact, it seems quite likely that life exists everywhere out there. And given that sapient, tool-using life evolved here, it seems quite probable that sapient, tool-using life evolved somewhere else as well…indeed, quite often. (Given that our local galactic supercluster contains literally quadrillions of stars, if sapient life exists in only one one-hundredth of one percent of the places life evolved and if life evolves in only one one-hundredth of one percent of the places that have planets, the universe should be positively teeming with sapience.)

These aren’t stars. They’re galaxies. Where is everyone? (Image: Hubble Space Telescope)

These aren’t stars. They’re galaxies. Where is everyone? (Image: Hubble Space Telescope)When you’re sapient and tool-using, radio waves are obvious. It’s difficult to imagine getting much beyond the steam engine without discovering them. Electromagnetic radiation bathes the universe, and most any tool-using sapience will, sooner or later, stumble across it. All kinds of technologies create, use, and radiate electromagnetic radiation. So if there are sapient civilizations out there, we should see evidence of it–even if they aren’t intentionally attempting to communicate with anyone.

But we don’t.

So the question is, why not?

This is Fermi’s paradox, and researchers have proposed three answers: we’re first, we’re rare, or we’re fucked. I have, until now, been leaning toward the “we’re rare” answer, but more and more, I think the answer might be “we’re fucked.”

Let’s talk about the “first” or “rare” possibilities.

The “first” possibility posits that our planet is exceptionally rare, perhaps even unique–of all the planets around all the stars everywhere in the universe, no other place has the combination of ingredients (liquid water and so on) necessary for complex life. Alternately, life is common but sapient life is not. It’s possible; there’s nothing especially inevitable about sapience. Evolution is not goal-directed, and big brains aren’t necessarily a survival strategy more common or more compelling than any other. After all, we’re newbies. There was no sapient life on earth for most of its history.

Assuming we are that unique, though, seems to underestimate the number of planets that exist, and overestimate the specialness of our particular corner of existence. There’s nothing about our star, our solar system, or even our galaxy that sets it apart in any way we can see from any of a zillion others out there. And even if sapience isn’t inevitable–a reasonable assumption–if life evolved elsewhere, surely some fraction of it must have evolved toward sapience! With quadrillions of opportunities, you’d expect to see it somewhere else.

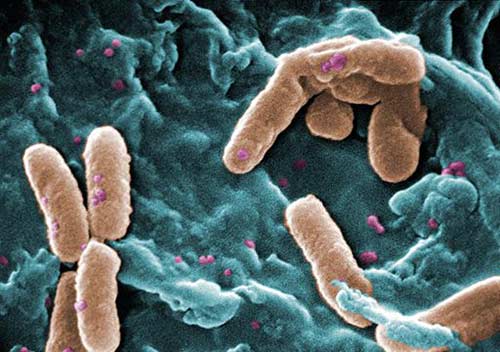

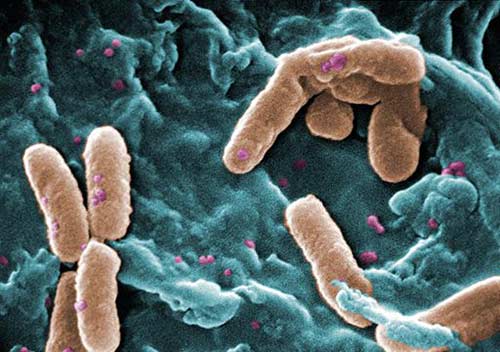

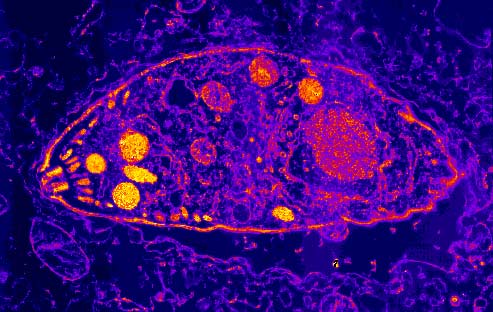

The “we’re rare” hypothesis posits that life is common, but life like what we see here is orders of magnitude less common, because something happened here that’s very unlikely even on galactic or universal scales. Perhaps it’s the jump from prokaryotes (cells without a nucleus) to eukaryotes (cells with a nucleus, which are capable of forming complex multicellular animals). For almost the entire history of life on earth, only single-celled life existed, after all; multicellular life is a recent innovation. Maybe the universe is teeming with life, but none of it is more complex than bacteria.

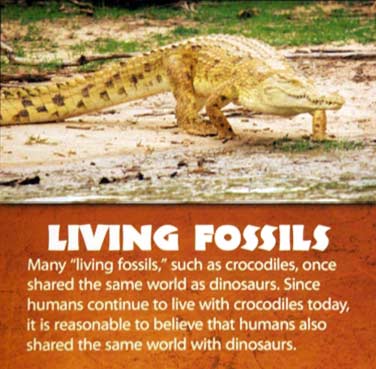

Depressing thought: The universe has us and these guys in it, and that’s it.

Depressing thought: The universe has us and these guys in it, and that’s it.The third hypothesis is “we’re fucked,” and that’s the one I’m most concerned about.

The “we’re fucked” hypothesis suggests that sapient life isn’t everywhere we look because wherever it emerges, it gets wiped out. It might be that it gets wiped out by a spacefaring civilization, a la Fred Saberhagen’s Berserker science fiction stories.

But maybe…just maybe…it won’t be an evil extraterrestrial what does us in. Maybe tool-using sapience intrinsically contains the seeds of its own annihilation.

K. Eric Drexler wrote a book called Engines of Creation, in which he posited a coming age of nanotechnology that would offer the ability to manipulate, disassemble, and assemble matter at a molecular level.

It’s not as farfetched as it seems. You and I, after all, are vastly complex entities constructed from the level of molecules by programmable molecular machinery able to assemble large-scale, fine-grained structures from the ground up.

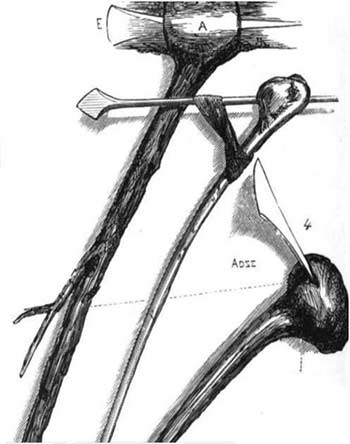

All the fabrication technologies we use now are, in essence, merely evolutionary refinements on stone knives and bearskins. When we want to make something, we take raw materials and hack at, carve, heat, forge, or mold them into what we want.

Even the Large Hadron Collider is basically just incremental small improvements on this

Even the Large Hadron Collider is basically just incremental small improvements on thisThe ability to create things from the atomic level up, instead from big masses of materials down, promises to be more revolutionary than the invention of agriculture, the Iron Age, and the invention of the steam engine combined. Many of the things we take for granted–resources will always be scarce, resources must always be distributed unequally, it is not possible for a world of billions of people to have the standard of living of North America–will fade like a bad dream. Nanotech assembly offers the possibility of a post-scarcity society1.

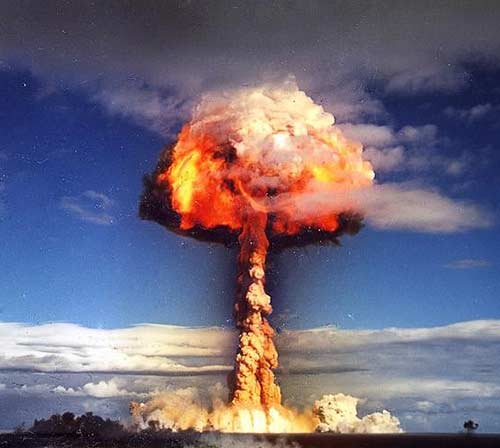

It also promises to turn another deeply-held belief into a myth: Nuclear weapons are the scariest weapons we will ever face.

Molecular-level assembly implies molecular-level disassembly as well. And that…well, that opens the door to weapons of mass destruction on a scale as unimaginable to us as the H-bomb is to a Roman Centurion.

Cute little popgun you got there, son. Did your mom give you that?

Cute little popgun you got there, son. Did your mom give you that?Miracle nanotechnology notwithstanding, the course of human advancement has meant the distribution of greater and greater destructive power across wider and wider numbers of people. An average citizen today can go down to Wal-Mart and buy weapon technology that could have turned the tide of some of the world’s most significant historical battles. Even without nanotech, there’s no reason to think weapons technology and distribution just suddenly stopped in, say, 2006, and will not continue to increase from here on.

And that takes us to millennialist zealotry.

There are, in the world today, people who believe they have a sacred duty, given them by omnipotent supernatural entities, to usher in the Final Conflict between good and evil that will annihilate all the wicked with righteous fire, purging them from God’s creation. These millennialists don’t just believe the End is coming–they believe God has charged them with the task of bringing it about.

Christian millennialists long for nuclear war, which they believe will trigger the Second Coming. Some Hindus believe they must help bring about the end of days, so that the final avatar of Vishnu will return on a white horse to bring about the end of the current cycle and its corruption. In Japan, the Aum Shinrikyo sect believed it to be their duty to create the conditions for nuclear Armageddon, which they believed would trigger the ascendancy of the sect’s leader Shoko Asahara to his full divine status as the Lamb of God. Judaism, Islam, and nearly all other religious traditions have at least some adherents who likewise embrace the idea of global warfare that will cleanse the world of evil.

The notion of the purification of the world through violence is not unique to any culture or age–the ancient Israelites, for example, were enthusiastic fans of the notion–but it has particularly deep roots in American civic culture, and we export that idea all over the world. (The notion of the mythic superhero, for instance, is an embodiment of the idea of purifying violence, as the book Captain America and the Crusade Against Evil explains in some depth.)

The notion of the purification of the world through violence is not unique to any culture or age–the ancient Israelites, for example, were enthusiastic fans of the notion–but it has particularly deep roots in American civic culture, and we export that idea all over the world. (The notion of the mythic superhero, for instance, is an embodiment of the idea of purifying violence, as the book Captain America and the Crusade Against Evil explains in some depth.)

I’m not suggesting that religious zealots have a patent on inventive destructiveness. From Chairman Mao to Josef Stalin, the 20th century is replete with examples of secular governments that are as gleefully, viciously bonkers as the most passionate of religious extremists.

But religious extremism does seem unique in one regard: we don’t generally see secularists embracing the fiery destruction of the entire world in order to cleanse os of evil. Violent secular institutions might want resources, or land, or good old-fashioned power, but they don’t usually seem to want to destroy the whole of creation in order to invoke a supernatural force to save it.

Putting it all together, we can expect that as time goes on, the trend toward making increasingly destructive technology available to increasingly large numbers of people will likely continue. Which means that, one day, we will likely arrive at the point where a sufficiently determined individual or small group of people can, in fact, literally unleash destruction on a global scale.

Imagine that, say, any reasonably motivated group of 100 or more people anywhere in the world could actually start a nuclear war. Given that millennialist end-times ideology is a thing, how safe would you feel?

It is possible, just possible, that we don’t see a ubniverse teeming with sapient, tool-using, radio-broadcasting, exploring-the-cosmos life because sapient tool-using species eventually reach the point where any single individual has the ability to wipe out the whole species, and very shortly after that happens, someone wipes out the whole species.

“But Franklin,” I hear you say, “even if there are human beings who can and will do that, given the chance, that doesn’t mean space aliens would! They’re not going to be anything like us!”

Well, right. Sure. Other sapient species wouldn’t be like us.

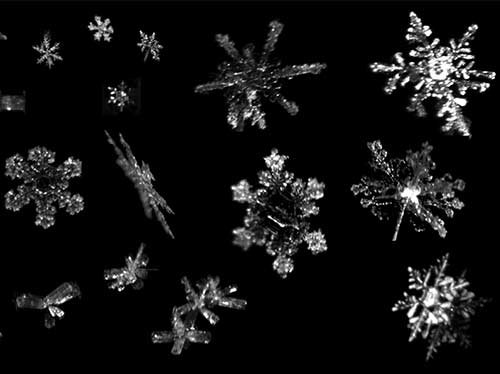

But here’s the thing: We are, it seems, pretty unremarkable. We live on an unremarkable planet orbiting an unremarkable star in an unremarkable corner of an unremarkable galaxy. We’re probably not special snowflakes; statistically, the odds are good that the trajectory we have taken is, um, unremarkable.

Yes, yes, they’re all unique and special…but they all have six arms, too.

Yes, yes, they’re all unique and special…but they all have six arms, too.

(Image: National Science Foundation.)Sure, sapient aliens might be, overall, less warlike and aggressive (or more warlike and aggressive!) than we are, but does that mean every single individual is? If we take millions of sapient tool-using intelligent species and give every individual of every one of those races the ability to push a button and destroy the whole species, how many species do you think would survive?

Perhaps the solution to the Fermi paradox is not that we’re first or we’re rare; perhaps we’re fucked. Perhaps we are rolling down a well-traveled groove, worn deep by millions of sapient species before us, a groove that ends in a predictable place.

I sincerely hope that’s not the case. But it seems possible it might be. Maybe, just maybe, our best hope to last as long as we can is to counter millennial thinking as vigorously as possible–not to save us, ultimately, but to buy as much time as we possibly can.

1Post-scarcity society of the sort that a lot of transhumanists talk about may never really be a thing, given there will always be something that is scarce, even if that “something” is intangible. Creativity, for instance, can’t be mass-produced. But a looser kind of post-scarcity society, in which material resources are abundant, does have some plausibility.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Consider this protein. It’s a model of a protein called AVPR-1a, which is used in brain cells as a receptor for the neurotransmitter called vasopressin.

Consider this protein. It’s a model of a protein called AVPR-1a, which is used in brain cells as a receptor for the neurotransmitter called vasopressin. To quote from one of my favorite George Carlin skits: “Now, if you think you do have rights, one last assignment for you. Next time you’re at the computer, get on the Internet, go to Wikipedia. When you get to Wikipedia, in the search field for Wikipedia, I want you to type in “Japanese Americans 1942, and you’ll

To quote from one of my favorite George Carlin skits: “Now, if you think you do have rights, one last assignment for you. Next time you’re at the computer, get on the Internet, go to Wikipedia. When you get to Wikipedia, in the search field for Wikipedia, I want you to type in “Japanese Americans 1942, and you’ll  Personhood theory as an ethical framework isn’t (directly) related to abortion at all. As an ethical principle, the idea behind personhood theory is pretty straightforward: “Personhood,” and with it all the rights that we now call “human rights,” belongs to any sapient entity.

Personhood theory as an ethical framework isn’t (directly) related to abortion at all. As an ethical principle, the idea behind personhood theory is pretty straightforward: “Personhood,” and with it all the rights that we now call “human rights,” belongs to any sapient entity. The arch-conservative, Creation “Science” Discovery Institute says of personhood theory, “In this new view on life, each human being doesn’t have moral worth simply and merely because he or she is human, but rather, we each have to earn our rights by possessing sufficient mental capacities to be considered a person. Personhood theory provides moral justification to oppress and exploit the most vulnerable human beings.”

The arch-conservative, Creation “Science” Discovery Institute says of personhood theory, “In this new view on life, each human being doesn’t have moral worth simply and merely because he or she is human, but rather, we each have to earn our rights by possessing sufficient mental capacities to be considered a person. Personhood theory provides moral justification to oppress and exploit the most vulnerable human beings.”  It is trivially demonstrable, even if we can not objectively state with absolute certainty, that something is sapient, that all of us at some time or another are not sapient. A human being who is under general anesthesia would fail any test for sapience, or indeed awareness of any sort. A sleeping person is less sentient than an awake dog. I myself am rarely sapient before 9 AM under the best of circumstances. (It is beyond the scope of this discussion to ponder whether a person who is in an irreversible coma or whose mind has been destroyed by Alzheimer’s still has the same rights as any other person; whether or not things like euthanasia are ethical is irrelevant to the concept of personhood theory as I am discussing it.)

It is trivially demonstrable, even if we can not objectively state with absolute certainty, that something is sapient, that all of us at some time or another are not sapient. A human being who is under general anesthesia would fail any test for sapience, or indeed awareness of any sort. A sleeping person is less sentient than an awake dog. I myself am rarely sapient before 9 AM under the best of circumstances. (It is beyond the scope of this discussion to ponder whether a person who is in an irreversible coma or whose mind has been destroyed by Alzheimer’s still has the same rights as any other person; whether or not things like euthanasia are ethical is irrelevant to the concept of personhood theory as I am discussing it.)

The Culture novels are interesting to me because they are imagination writ large. Conventional science fiction, whether it’s the cyberpunk dystopia of William Gibson or the bland, banal sterility of (God help us) Star Trek, imagines a world that’s quite recognizable to us….or at least to those of us who are white 20th-century Westerners. (It’s always bugged me that the alien races in Star Trek are not really very alien at all; they are more like conventional middle-class white Americans than even, say, Japanese society is, and way less alien than the Serra do Sol tribe of the Amazon basin.) They imagine a future that’s pretty much the same as the present, only more so; “Bones” McCoy, a physician, talks about how death at the ripe old age of 80 is part of Nature’s plan, as he rides around in a spaceship made by welding plates of steel together.

The Culture novels are interesting to me because they are imagination writ large. Conventional science fiction, whether it’s the cyberpunk dystopia of William Gibson or the bland, banal sterility of (God help us) Star Trek, imagines a world that’s quite recognizable to us….or at least to those of us who are white 20th-century Westerners. (It’s always bugged me that the alien races in Star Trek are not really very alien at all; they are more like conventional middle-class white Americans than even, say, Japanese society is, and way less alien than the Serra do Sol tribe of the Amazon basin.) They imagine a future that’s pretty much the same as the present, only more so; “Bones” McCoy, a physician, talks about how death at the ripe old age of 80 is part of Nature’s plan, as he rides around in a spaceship made by welding plates of steel together.

But I wonder…would a post-scarcity society necessarily be Utopian?

But I wonder…would a post-scarcity society necessarily be Utopian? One such society might be the Aztec empire, which spread through the central parts of modern-day Mexico during the 14th century. The Aztecs were technologically sophisticated and built a sprawling empire based on a combination of trade, military might, and tribute.

One such society might be the Aztec empire, which spread through the central parts of modern-day Mexico during the 14th century. The Aztecs were technologically sophisticated and built a sprawling empire based on a combination of trade, military might, and tribute.

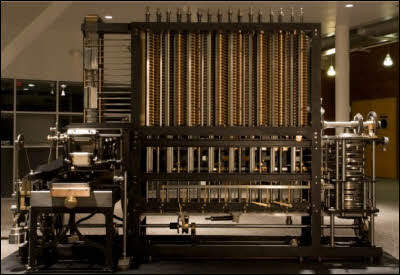

Babbage reasoned–quite accurately–that it was possible to build a machine capable of mathematical computation. He also reasoned that it would be possible to construct such a machine in such a way that it could be fed a program–a sequence of logical steps, each representing some operation to carry out–and that on the conclusion of such a program, the machine would have solved a problem. Ths last bit differentiated his conception of a computational engine from other devices (such as the Antikythera mechanism) which were built to solve one particular problem and could not be programmed.

Babbage reasoned–quite accurately–that it was possible to build a machine capable of mathematical computation. He also reasoned that it would be possible to construct such a machine in such a way that it could be fed a program–a sequence of logical steps, each representing some operation to carry out–and that on the conclusion of such a program, the machine would have solved a problem. Ths last bit differentiated his conception of a computational engine from other devices (such as the Antikythera mechanism) which were built to solve one particular problem and could not be programmed. Now, when I was in school studying neurobiology, things were very simple. You had two kinds of cells in your brain: neurons, which did all the heavy lifting involved in the process of cognition and behavior, and glial cells, which provided support for the neurons, nourished them, repaired damage, and cleaned up the debris from injury or dead cells.

Now, when I was in school studying neurobiology, things were very simple. You had two kinds of cells in your brain: neurons, which did all the heavy lifting involved in the process of cognition and behavior, and glial cells, which provided support for the neurons, nourished them, repaired damage, and cleaned up the debris from injury or dead cells.

Right now, most attempts to model the brain look only at the neurons, and disregard the glial cells. Now, there’s value to this. The brain is really (really really really) complex, and just developing tools able to model billions of cells and hundreds or thousands of billions of interconnections is really, really hard. We’re laying the foundation, even with simple models, that lets us construct the computational and informatics tools for handling a problem of mind-boggling scope.

Right now, most attempts to model the brain look only at the neurons, and disregard the glial cells. Now, there’s value to this. The brain is really (really really really) complex, and just developing tools able to model billions of cells and hundreds or thousands of billions of interconnections is really, really hard. We’re laying the foundation, even with simple models, that lets us construct the computational and informatics tools for handling a problem of mind-boggling scope.