Group sex. It’s arguably one of the most common sexual fantasies that exists, right up there with the one about your French teacher, a paddle, and a giant pot of honey. It’s also one of the most fraught: How do I find people who want to have a threesome? What happens if I’m with a partner who’s more into the third person than into me? What if I get jealous? What if my partner gets jealous? What if there’s Drama? What if I feel left out?

I’m a huge fan of group sex. I lost my virginity in an MFM threesome (something I talk about in my memoir The Game Changer), and in the time since I’ve had far too many threesomes (and quite a lot of foursomes, and a few fivesomes, and some elevensomes, and at least one fifteensome) to count.

Group sex is hella fun, though like any kind of sexual activity it’s not everyone’s cup of tea, and that’s okay. If group sex is something that interests you, it can be hard to know where to get started and how to stack the deck in favor of a good experience for everyone. That’s what this guide is for.

What is group sex like? Fun. I’ve consistently found it to be amazing. First, though, I’ll talk about what it’s not like.

What group sex isn’t

It’s not (usually) like what you see in porn flicks or Hollywood movies. The other folks involved are people; unless you’ve hired a pair of sex workers, they’re not there just to be part of a male wank fantasy.

I’m afraid I have some bad news for the straight dudes in the audience: When you’re having sex with two (or more) women, they’re not there just for you. It’s not all about you and your pleasure. A typical threesome wank fantasy is about two women who make out or have sex with each other just to get the dude hot, but secretly they both need the D.

That’s not likely to be how it happens. Maybe they’re both straight. Maybe they’re both bi and more into each other than him. Like I said, I’ve had a threesome with a bi woman and her lesbian girlfriend; we both paid attention to the bi woman, but her girlfriend and I had no contact at all. It was all about the bi woman, not all about me.

In fact, threesomes with two men are about as common as threesomes with two women–and no, you don’t need to be bisexual to have a threesome. Three men can have a threesome, as can three women. If you’re a straight guy, you also need not feel threatened by the presence of another penis in the room. As many women as men fantasize about threesomes, and often, women quite fancy the notion of two men paying attention to her as much as men like the idea of two women paying attention to him.

Which brings up another point: unless you’ve explicitly negotiated otherwise, you can’t assume it’s a free-for-all. You don’t get to do whatever you want with both of the other folks involved. Everyone is going to come to group sex with their own limits and boundaries. If you ever want to have a second threesome, pay attention to those boundaries! Yes, people are getting naked and sweaty. No, that doesn’t (necessarily) mean you get to have sex, or perform any particular act, with either or both of them. They have the right to say what you may or may not do with their bodies. (And so do you, by the way. You are never obligated to have sex with someone just because they’re involved in sex with someone else. I am straight, so when I have threesomes involving another guy, he and I don’t touch. That’s fine. Your body, your rules.)

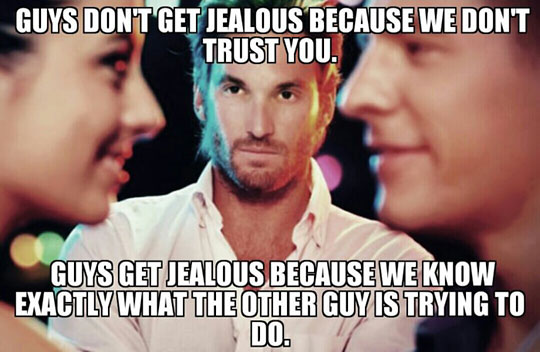

Finally, a lot of folks naively assume “if I’m with someone and we both have sex with the same third person, we won’t feel jealous because we’re both there!” Wrong. Jealousy is about insecurity, and it’s possible to feel insecure even when you and your partner are having sex with the same lover. The best time to get a handle on that is before you invite someone else into your bed, not after.

What group sex is

Fun. Lots and lots of fun. Threesomes can happen in a wide range of configurations with a wide range of activities that go way beyond the stereotypical porn shoot or wank fantasy. They offer virtually unlimited ways for three people to come together and explore.

There’s something delicious about having two sets of hands and lips and tongues on your body that’s just amazing. It’s fun to be the one receiving that attention, but it’s also fun to be participating in giving someone else that kind of pleasure.

It’s cozy. Three people all wrapped up together is really nice. It’s incredibly intimate, both physically and emotionally. I remember a situation where I, one of my girlfriends, and my FWB all spent the night together. We had lots of sex and fell asleep all tangled up together, but you know what the most fun part was? The next morning when we woke up and showered together. The three of us barely fit in the shower stall, and all of us were still sleepy and a bit giddy from the night before, and it was incredibly warm and cozy and intimate.

The sex is amazing. There are a lot of sensations and activities that are not possible with two people that are possible with three.

If you’re a straight dude in an FMF threesome, for instance, it’s not necessarily a question of having ordinary PIV intercourse with two women, though of course that can be part of it (and it’s hella fun when it is). I’m a big fan of pegging (having a woman use a strapon on me), and in threesomes, there are all kinds of fun combinations available. I’ve been on top of one lover having PIV sex with her while another lover is behind me pegging me…that was fun! (We broke the bed.) I’ve been lying on my side spooning a lover and penetrating her while another lover is spooning me and pegging me. There are all kinds of varieties in any kind of threesome, and a little imagination goes a long way.

It’s a lot of fun when bondage is involved, too. The night before my girlfriend and my FWB and I ended up in the shower together, my girlfriend and I tied my FWB to the bed and we both took turns playing with her. On another occasion, I was tied to the bed on my back while one lover straddled me and rode me, and another lover sat on my face. The two of them made out with each other while they both took pleasure from me. As you can imagine, both experiences were really hot.

So how do you make it work? What are the rules for group sex?

In my experience, the most important rules for threesomes (or foursomes or orgies or any other group sex) are not that different from the most important rules for two-person sex. Sex is sex, after all, and it doesn’t turn into something qualitatively different for n>2. As with any sex:

- The folks involved are people, not sex toys or objects for your pleasure. Their needs and desires matter just as much as yours.

- Consent matters. This means do not do things without someone else’s consent. Do not, for example, assume you have sexual access to everyone else involved. (I have had threesomes with two women where one of the women involved self-identified as lesbian. I have had threesomes with two women where one of the women was the girlfriend of my partner. In neither case did I assume that just because there were two women there, that meant I got to have sex with both of them.)

- Set and respect boundaries. Talk about what access you will and will not allow to you. You don’t have to have sex with all the other folks just because your orientations and/or wibbly bits line up!

- Talk about and plan for sexual health. Use barriers, exchange sexual histories, or do whatever else you need to do to protect your health.

- I have found that sex of all sorts usually goes better with friends than with strangers. It is common for people new to group sex to want to try it with strangers, because they fear that having sex with people they know will make things “awkward” or induce jealousy. In my experience, though, inviting a random person into your bed goes along with inviting random communication skill, random sets of expectations, random STI risk profile, and random risk of Drama into your bed. With friends, you’ve already established a baseline, I hope, of communication and trust. Those things make sex better.

- Communication matters. If you’re feeling something you didn’t expect, communicate! If you want (or don’t want) something to happen, communicate!

- Treat the other people with respect and compassion. They are people too, remember? Treating people well is the key to having everyone have a good experience. When you treat other people well, you might get to play again!

- If you do have an unexpected response, try to deal with it with grace. It’s okay to feel unexpected things when you try something new. If you need to stop, stop, but do so calmly and without shame, blame, or drama.

- Don’t spend all your time trying to script exactly what happens or how it goes, unless scripting sex is your particular kink. Sometimes people are tempted to try to avoid jealousy by using a script. That’s unlikely to work. Jealousy is caused by insecurity and it’s hard to navigate around insecurity with rules or scripts.

Special considerations for safer sex

Group sex poses special challenges for safer sex that you might not have to think about when you’re accustomed to the more one-on-one variety. In addition to being aware of transmitting potential pathogens to your partner or receiving them from your partner, you also have to be aware of transmitting them between participants.

Some of these guidelines are common sense. If you use barriers like condoms, for instance, don’t use the same barrier with two different partners. Change condoms when moving between partners.

The same goes for use of sex toys or fingers. Be aware of who you’ve touched and with what. Cover toys and change the coverings between partners, or use toys with only one partner. Don’t put your fingers in one person’s wibbly bits and then put them in another person’s bits, if those people aren’t fluid-bonded.

Oral sex requires particular care. We don’t necessarily think of it as a vector between two folks who aren’t directly intimate with each other, but it can be. Use dental dams or condoms if you’re offering oral sex to two partners, or use mouthwash between partners. Be aware of where your bits have been, where your fingers have been, and yes, where your tongue has been.

Finding partners

Having group sex doesn’t take magic superpowers or arcane pickup secrets you learn from the seedier corners of the Internet. It does, however, help to let go of conventional attitudes about sex. We are all, throughout our lives, inculcated with a lot of baggage around sex, and some of that baggage makes it really hard to have threesomes.

In my experience, there are three approaches to trying to find group sex.

A lot of folks start out with a conventional relationship, then search for someone who will basically be an expendable fantasy fulfillment object. That can feel nice and safe. The third person is barely even a person. In fact, a lot of folks set strict rules on what that third person can and can’t do, or even set rules that it has to be an anonymous stranger from Craigslist rather than a friend or acquaintance, in the belief that this will avoid jealousy or awkwardness.

There are several problems with this approach. First, in my experience, the couples who do it are often trying to outsmart jealousy by planning and scripting a scenario they think will keep it at bay. But jealousy doesn’t come from sex. Jealousy comes from insecurity. If you see your partner enjoying someone else, and you’re sexually insecure, you will likely feel threatened and jealous even if the other person is a stranger, even if you’re having sex with that person at the same time, and even if you’re following a script. Second, sex with a stranger can feel less threatening than sex with a friend, but the problem is a random stranger brings random STI profile, random integrity or lack thereof, random baggage, and random drama to the table. Third, it encourages thinking of that person as a thing, not as a person with needs and desires.

It’s easier to take this approach than to build good tools for self-confidence, security, communication, and respect. A lot of folks take this approach because they don’t want to (or don’t know how to) build those tools, and the results are mixed. It is possible to have a good threesome with this approach, but it’s surprisingly hard. I think every threesome horror story I’ve ever heard (and I’ve heard quite a lot of them) started with this approach.

The second approach is to join a swing club or lifestyle community. This approach is really intimidating to a lot of people. There are all kinds of stereotypes about swingers, it can be hard to admit to other people what you want, and a lot of folks will say things like “sure, I want to have group sex, but that doesn’t mean I’m like all those perverts!” (Seriously, I’ve heard people say just that.)

The advantages to this approach are that it’s safe–the lifestyle community tends to have zero tolerance for abusive or disrespectful behavior, there is a strong culture of not disrupting other people’s relationships, there are meet and greets where you can get to know folks in the community in a low-pressure social setting without sex, and you’ll meet people who are on the same page about what you want. The disadvantage is that it’s intimidating at first, and if you’re still carrying around a bunch of baggage like sexual insecurity, sex negativity, or poor communication skills, you’re going to have to address those. It also can tend, depending on where you are, to favor people who are conventionally attractive. But the lifestyle community offers a structural way to get what you want on your terms.

My approach is different. I’ve never “found” a partner for a threesome by going out and looking. All the threesomes I’ve ever had have involved people I already knew. I’ve always had a social circle who are open and sex-positive, so I’ve never had to go out searching; it’s always been more like “hey, I like you, I’d like to explore bring more physically intimate with you, whaddya say?”

I’ve tried to work on myself to build strong self-esteem and security, to confront my fears and insecurities, to develop the qualities of integrity and transparency, to be able to talk about sex without fear or shame, and to let go of the idea that if my lover digs sex involving another person that means I’m not good enough or whatever.

I’ve also worked hard to understand three principles that sound obvious but aren’t:

- I can’t expect to have what I want if I don’t ask for what I want

- If I feel something bad or unpleasant that doesn’t necessarily mean someone else is doing something wrong

- Other people are real, which means their needs and desires are just as valid as mine.

Having done that, I deliberately built a social circle of open, sex-positive people. I got over feeling intimidated about going to kink or lifestyle social groups. I sought out people who have positive, healthy attitudes about sex. I worked on my own integrity.

And it really paid off. And because my social circle is made up of folks with good communication skills and positive attitudes about sex, it’s remarkably drama-free.

This approach takes the most work of the three, but it’s work you do on yourself. Being confident and secure, being open, having good communication skills, being willing to face down your fears and insecurities help you find partners, sure, but they also help you live a better, happier life.

Like this:

Like Loading...

But I am no fan of intentional dishonesty, even in small ways. The little white lie? It has effects that are farther reaching and more insidious than I think most folks realize.

But I am no fan of intentional dishonesty, even in small ways. The little white lie? It has effects that are farther reaching and more insidious than I think most folks realize. When you tell little white lies, however harmless they may seem, you are telling your partner, Don’t believe me. Don’t believe me. I will lie to you. I will tell you what you want to hear. Don’t believe me.

When you tell little white lies, however harmless they may seem, you are telling your partner, Don’t believe me. Don’t believe me. I will lie to you. I will tell you what you want to hear. Don’t believe me.