I’m typing this in Springfield, Missouri, where I’ve just returned from visiting several places that do not yet exist, and won’t exist for nearly two thousand years.

Lemme back up a bit.

My Talespinner and I are writing a novel. Specifically, we’re writing a rather chonky (~160,000 word) far-future, post-Collapse magical realism literary novel called Spin, set in the Dominionate, a sort of quasi-Catholic/Calvinist theocracy that extends through much of the center of what is now the United States.

We are, as I write this, about 90,000 words in, and we were having difficulty nailing down a crucial bit of timing, when our protagonist is forced by an encounter with the Inquisition to head off-road through what is now rural Missouri, trying to reach the city of Kanzit, the capital of the Dominionate and home to a character she hopes can save her.

We’ve looked at maps and Google Earth, measured distances, made calculations, and finally my Talespinner was like “You know what? Fuggit. Ima follow her path and see how long it would take.”

About this time, I received a letter from Oregon Revenue, informing me I’d made an error in my 2022 state income tax (cue heart attack)…and that I’d overpaid by $208 (whew!). So I found a plane ticket for $206, and said “You know what, Ima go with you.”

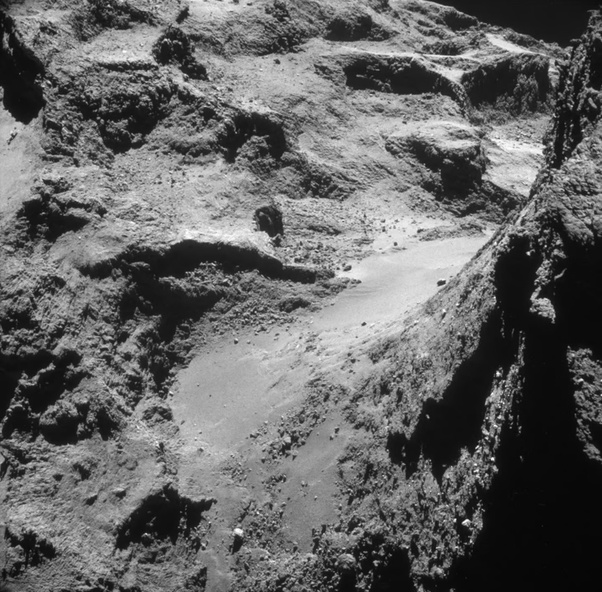

We started following the footsteps of our protagonist from modern-day Stockton State Park, a park on a small peninsula jutting into Stockton Lake.

In two thousand years, after the Great Collapse, sea level rise, and two smaller collapses, this will become the small village of Half-Circle Cothold, where our protagonist Aiyah Spinner was born and raised.

On this spot, right here, will be a church and Mother’s Cloister two millennia from now. From this very spot, Aiyah will begin her journey toward Kanzit, built on what was once Kansas City, a journey that will absolutely not go as she expects.

From here, her plan will be to cross the bridge into Bridgegate, heading toward Brightchurch and from there, Kanzit itself, following the ancient roads still maintained and used after all these years.

Ah, Brightchurch.

If Kanzit is the head of the Dominionate, Brightchurch is its heart, a walled city that hosts Brightchurch Cathedral, the Temple of a Thousand Lights, one of the wonders of the future world, destination of an endless river of pilgrims. Brightchurch Cathedral, its windows shining like God’s grace itself every moment of every day and night, thanks to thousands of oil lamps fed from a cunning engineering marvel that distributes oil through a vast system of tubes and pipes, driven by pumps powered by human and animal muscle, tended by an army of novices, awe-inspiring beyond imagination. (The idea for Brightchurch Cathedral came from a pen and paper role-playing game I ran for a time a few years back, expanded and incorporated into the world of the Dominionate.)

Brightchurch Cathedral will one day stand on this spot, right here, in present-day Nevada, Missouri.

(Honestly, I would never for a moment want to live in the Dominionate, but I nevertheless wish I could see Brightchurch Cathedral. It’s truly a magnificent, incomprehensibly beautiful place.)

Aiyah, for various reasons, never reaches Brightchurch, but instead is forced to flee overland, through what is now farmland but will be, in the age of the Dominionate, forest. We followed her path, and I’m so glad we did, because we found all kinds of treasures along the way.

Like this tiny graveyard, which isn’t on any map or on Google Maps, but lies directly in her path and some remnant of which may still exist in the time the novel is set.

As for Kanzit, while it’s much reduced and sees countless changes, some of its buildings still exist, lovingly maintained over countless years.

The administrative center of the Church and, by extension of all the Dominionate lives in what is now the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, suited by both design and location to be repurposed to the head of the theocratic government. All the various aspects of the Church except the Inquisition are administered from here.

So let’s talk about the Dominionate.

When this novel publishes, I think people will compare it to The Handmaid’s Tale. The two stories have some superficial resemblances: social collapse, a theocracy carved out of what was once the United States, falling fertility that leads to sexual subjugation of women.

But that’s where the similarities end.

Margaret Atwood has said she explicitly modeled the government and culture of Gilead on the Islamic Revolution, a cautionary tale about what might happen in a society where reactionary religious zealotry comes to power.

But when I read The Handmaid’s Tale, I came away from the story with a sense that Gilead is fundamentally unstable. On a very deep level, the society doesn’t really work for anyone. Everyone is miserable—even the people on the top of the hierarchy. Offred, certainly, and all the other Handmaids…but even the Commander comes across as fundamentally unhappy. You really can’t point to anyone in Atwood’s story and say “yeah, those folks have a pretty good life, they seem happy and self-actualized.”

Which is, I think, part of the point she’s making.

The thing that makes Spin so horrifying, so deeply disturbing, is that the Dominionate works. The society of the Dominionate has long-term stability, peace, and prosperity. Many people—most people, really—are happy. Or if not happy, at least content. There’s little violence or crime. That sets Spin in sharp contrast to The Handmaid’s Tale (well, that and the fact Spin incorporates elements of magic, and a vastly different story).

Technology in the Dominionate is limited—the thing about the modern world is that we’ve largely stripped the earth of natural resources available to anyone without a post-industrial level of technology (there are no more surface deposits of iron, copper, tin, or coal, no oil available without modern drilling techniques, and without vast and available fuel, you might be able to “mine” landfills or junkyards for metals but you will have a very difficult time indeed smelting modern steels into things you can use)—but our knowledge remains. Even without modern levels of technology, most people still have a reasonably high standard of living.

But all of it—their standard of living, their society, their peace and prosperity—rests on a foundation of subjugation of (some) women. There’s no escaping it. They hide it away, in Mother’s Cloisters administered by the Church, and it’s been normalized for so long that everyone, even the people most oppressed, accept it as natural and necessary.

That is, I believe, way more horrifying than the society of Gilead, a society that does not have peace and prosperity, a society that seems unlikely to endure for two hundred years, or honestly even for twenty.

And more horrifying still, you can make a strong argument that the oppression and subjugation of the Dominionate is necessary. Without it, humanity will likely cease to be. Squaring that circle—trying to reconcile the idea that humanity has value with the horrific bedrock strata of sexual slavery on which not just this particular society but humanity’s future rests—is the core of the novel.

Spin is by far the most challenging, most ambitious writing project I’ve ever been part of. My Talespinner and I didn’t set out to write it this way. We’d originally imagined an 80,000-word young adult novel, something far more lighthearted. About 25,000 words in, we realized that story didn’t actually worked, tore it up, sat down, re-thought the story we wanted to tell, and came up with a detailed 27-page outline for something much, much different…and much, much darker.

I am absolutely thrilled my Talespinner and I took the opportunity to make this trip, following a character’s journey two thousand years from now. Everything we saw along the way will inform the novel. We have quite a lot of rewriting to do, particularly in the first third of the book, which will be far richer and more vibrant because we did this crazy thing.

I’m also profoundly grateful that one of my Talespinner’s other lovers was able to accompany us. His presence made the trip better, but even more, as we took copious notes—I still haven’t transcribed them into the outline yet—he offered ideas and suggestions that will make the novel so much better.