[Note: This entry originally started out as an answer on Quora.]

So apparently there’s a dude named Russell Brand. I will admit, Gentle Readers, that I don’t know who he is, except that apparently he does standup comedy and such, and apparently his YouTube videos have been demonetized after he was accused of sexual assault.

Now, I will freely confess to knowing somewhere between zip and fuckall about him, his life, or the accusations. That’s not actually what this essay is about. Instead, I’d like to dive into the murky world of social media, monetization, and the ethics we as a society choose to live by.

I wrote the first version of this essay when a Quora user asked if YouTube has the legal right to demonetize Brand as ‘punishment’ for being accused of assault. Which is completely the wrong question. Punishment is something one does as retribution for an offense. Punishment is about the person being punished. YouTube doesn’t care about him, it cares only about its own brand. He’s not being removed so that YouTube can punish him, he’s being removed because not removing him hurts Google’s cash flow. (Google, naturally, owns YouTube.)

Does YouTube have a legal right to do this? Yes.

Does YouTube have a moral right? Well…that gets complicated. Buckle up, long essay is loooooong.

The legal part is straightforward, so I won’t spend a lot of time on it. When you create a YouTube account and click I Agree, you have signed a legally binding, court-enforceable contract with Google. That contract gives Google the absolute, unlimited, unilateral right to demonetize you or kick you off their platform for any reason or no reason. YouTube’s servers are private property owned by Google, they are not a public forum or a public space, and you are not the customer, their advertisers are the customer.

In the eyes of the law, this is what clicking “I accept” means. If you don’t like the contract, don’t sign. (Image: Scott Graham)

Legally and morally, you have no right to use YouTube or its servers. You are granted a limited, revokable permission to use private property belonging to Google under certain conditions, and that permission can be withdrawn at any time for any reason.

Legally, it’s open and shut. Nothing to see here, move along.

Ethically?

I think an argument can be made that it’s ethically dodgy. Trouble is, the ethical argument isn’t the one people are making.

First off, anyone who tells you “First Amendment my constitutional rights!” in any discussion about social media is an imbecile, and you can safely disregard any ignorant bleatings that issue forth from their pie-hole. You have no Constitutional right whatsoever to use someone else’s stuff for free.

“But it’s a public forum!” No, it isn’t. Shut up, you’re embarrassing yourself. It’s a private server, owned by a corporation and maintained at that corporation’s expense. You have no right to be there.

“But it gives big tech companies too much power!” And? And so? People who own communications media have always had that much power. Social media is, in fact, way more democratized than newspapers or television stations, and guess what? You have no right to march into a television studio and demand they broadcast whatever you want them to on the six o’clock news, or to demand that Time Magazine publishes your manifesto on toothbrush design.

Google data center. This is private property. You have no right to use this for free.

Magazine printing press. This is private property. You have no right to use this for free. (Image: Bank Phrom)

People who own media set the rules for what that medis will carry. That’s the way it’s always been, that’s the way the Founding Fathers intended it to be (many of them were media owners themselves!), and government regulations telling media owners they have to carry your stuff is an infringement on their First Amendment rights.

The actual ethical argument is way, way more subtle, and it’s not about the Constitution, it’s about the kind of society we want to live in.

So liberals and conservatives, as part of the tedious ongoing culture war designed to distract attention from the fact that the conservative party in the US no longer has a party platform or legislative agenda, have latched onto this idea of “cancel culture” as a stick to beat each other with.

Ironic, since liberals and conservatives both do it. It’s just that when they do it, they’re imposing their ideology by force on other people, but when we do it, we are making society safer by choosing to spend our money in ways that promote the ideals we want to see.

It’s asinine because all the folks engaging in this argument, left or right, are liars. They may see themselves as genuinely good people, but they’re still liars. And the thing about seeing yourself as a good person is, you stop watching yourself. You stop asking yourself ethical questions. Once you’ve accepted that you’re a good guy, it follows that what you’re doing must be right, because you’re a good guy, and good guys do the right thing. It’s written on the tin!

I’d far rather be trapped all night in a dark basement with someone who questions his own moral worth than someone utterly convinced he’s on the side of the angels, hands down.

But I digress.

The actual ethical issue is the issue of mob rule: the tyranny of torch and pitchfork.

A crowd of “good people” (Image: Hert Niks)

Why does Google revoke YouTube monetization for someone who’s been accused of something bad? Because if they don’t, advertisers will harm their revenue.

Why would advertisers harm their revenue? Is it because the corporations buying the ads are all fed from the milk of human kindness, motivated above all things by the desire to bring justice to the world?

Ah HA ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha nope.

It’s because advertisers fear an angry backlash if they don’t.

Why do advertisers fear an angry backlash if they don’t?

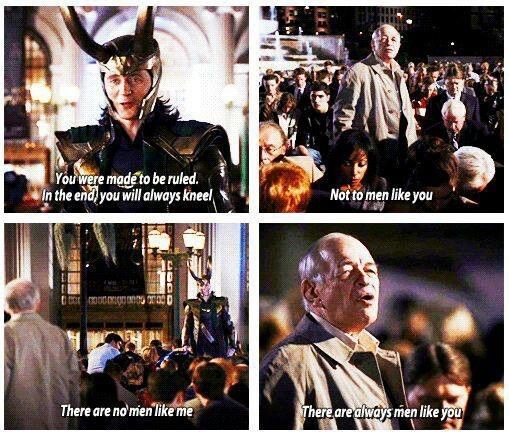

Because the Internet allows people to come together in flash mobs to punish the transgressors on a moment’s notice, and punish those standing next to the transgressors, and punish those who are insufficiently righteous in their zeal against the transgressors, and those who stand next to those who are insufficiently righteous in their zeal against the transgressors, and those who are peripherally associated in any way with anyone associated with the transgressors.

And these Internet flash mobs are fast. Much faster than the speed of Truth or Reason. In fact, in many corners it is considered morally wrong to suggest that maybe people ought to slow down to the speed of reason.

Just like Google has the right to decide you can’t use its servers for free for any reason or no reason, you have the right to decide you won’t buy Happy Pawz Cat Litter™ for any reason or no reason…including that you saw an ad for Happy Pawz Cat Litter™ on a YouTube video about cello tuning and you hate cello music. Or you don’t like the person in the video, or the person who made the video, or the person the video is about. Whatever. Your money, your rules.

And you have the right to tell other people “I really don’t care for Happy Pawz Cat Litter™ and I don’t think you should buy it either.”

So far, so good.

The place it runs off the rails is when “I won’t support X for reason Y” becomes “I will make sure nobody supports X for reason Y, and anyone who disagrees with me is Clearly Evil and must be punished too.”

In other words, it’s about locus of control. I will control how I spend my money: totally okay. I will control how you spend your money: Abusive, bullying, and toxic.

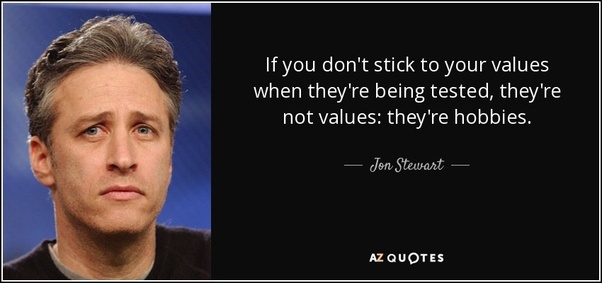

This is often framed as a liberal vs conservative thing. It’s not. It’s an authoritarian vs self-detemining thing.

No matter how pure your intentions or righteous your cause, if you deprive others of the ability to disagree with you, you are a bully.

And that’s the greatest secret of the Internet: it empowers bullies in ways no other technology ever has.

This, but electronically, is the ethical issue (image: egoitz)

Russel Brand may well be a terrible person. If you don’t want to support him, that’s cool. If you believe nobody should support him, that’s cool. If you believe Google shouldn’t give him money for his YouTube content, that’s cool.

If you believe everyone else must think as you do, that’s not cool.

People really struggle with this, because at the end of the day, bullying feels good. There’s a reason it’s such an enduring part of the human experience. And bullying in the name of a virtuous cause? That feels awesome. It feels righteous. You’re Striking A Blow Against Evil! You’re making the world a better, more just place!

You can build utopia if only you can foce everyone to harass, shun, and exclude the people you think should be harassed, shunned, and excluded! Why won’t people see that we will all become more egalitarian and empowered if everyone would just do as I say??? What is wrong with them?

So that’s the world Google lives in: if they monetize the wrong people, there’s a real chance their advertisers will be harassed. I mean, think what happened when radio stations continued to play the Dixie Chicks when the torches and pitchforks crowd started the crusade against them—managers of radio stations were stalked, their families received rape and death threats.

Building Utopia by finding the right people to threaten and bully, amirite?

Now, I will admit I have a dog in this fight. I woke up a while back to discover that a person posing as a journalist had put up a website where a bunch of people claiming to be exes of mine—some exes, some not, some people I’ve never been in the same room with except in passing at a convention or something—were claiming to have been abused by me. It’s a…weird and unsettling experience to have people saying that more exes have come forward with tales of abuse than the total number of exes you have.

Anyway, as a result of that, owners of indie bookstores have been harassed for hosting book events with my co-author and me. People close to me have been threatened. A BBC reporter wrote a book on polyamory, and ended up being harassed after someone started a rumor that I actually wrote the book and used his name. He used to do a podcast; that ended when his co-host was harassed to the point she didn’t feel safe associating with him any more. Even though you can look up his name and yes, he’s actually a well-known and well-established British reporter…who is, in fact, not me.

And most bizarre of all, someone started an Internet rumor that I secretly run a polyamory conference put on by a British non-profit in London, and as a direct result, people scheduled to speak at that conference received a barrage of death threats in a coordinated campaign so serious, the non-profit canceled the conference. A conference that (it shouldn’t be necessary to point out but I’ll say it anyway) I do not run, profit from, or in any other way have connection with—as is easily verifiable because it is, err, run by a British nonprofit, and like all British nonprofits, its managers, members, and finances are all public record.

Not that pitchfork mobs are known for, you know, doing their research.

So I have firsthand experience with this kind of crap.

Now, absolutely none of this has anything to do with whether Russel Brand is a good person or not, whether Russel Brand is guilty or not, or whether Russel Brand deserves (for whatever value of “deserves” one might use) a platform or not.

The point is, it’s totally 100% ethical to say that you won’t spend your money with anyone who supports people you don’t like. Your money, your rules.

There is an ethical issue here. The ethical issue isn’t “but the First Amendment! Freeze peach!” The ethical issue isn’t “but public forum!” The ethical issue isn’t “but Big Tech has too much power!” Anyone yapping about that can forever be ignored.

The ethics are that we live in a world where if your radio station plays music from someone that the Internet horde doesn’t like, your managers will be stalked, their families threatened with rape and dismemberment, and venues that host their concerts will receive bomb threats.

Image: Ahasanara Akter

The ethics are that we live in a world where this sort of thing is so common, and so normalized, and so rationalized, that companies would rather preemptively cut people off if it seems like there’s a possibility that the Internet horde might pick up the pitchforks and torches.

I do absolutely 100% see that as a problem. In fact, I’ll even go one step further and say it might be one of the defining social problems of the modern age, a direct consequence of populism and a sense of entitlement common on all sides of the political spectrum that says “I have the right to send rape and death threats if I think my cause is righteous and just enough—I am doing good with every rape threat I send, I am building a better society one rape and death threat at a time.”

I often wonder how someone sits down at a computer and types out an email describing how they’re going to murder someone on another continent they’ve never met, then clicks Send, dusts off their hands, and says “Today I did the right and just thing, look what a good person I am!”