In part 1 of this article, I blogged about leaving iOS when I traded my iPhone for an Android-powered HTC Sensation 4G, and how I came to detest Android in spite of its theoretical superiority to iOS and came back to the iPhone.

Part 1 talked about the particular handset I had, the T-Mobile version of the Sensation, a phone with such ill-conceived design, astronomically bad build quality, and poor reliability that at the end of the year I was on my third handset under warranty exchange–every one of which failed in exactly the same way.

Today, in Part 2, I’d like to talk about Android itself.

When I first got my Sensation, it was running Android 2.3, code-named “Gingerbread.” Android 3 “Honeycomb” had been out for quite some time, but it was a build aimed primarily at tablets, not phones. When I got my phone, Android 4 “Ice Cream Sandwich” was in the works, ready to be released shortly.

That led to one of my first frustrations with the Android ecosystem–the shoddy, patchwork way that operating system updates are released.

My phone was promised an update in the second half of 2011. This gradually changed to Q4 2011, then to December 2011, then to January 2012, then to Q1 2012. It was finally released on May 16 of 2012, nearly six months after it had been promised.

And I got off lucky. Many Motorola users bought smart phones just before the arrival of Android 4; their phones came with a written guarantee that an update to Android 4 would be published for their phones. It never happened. To add insult to injury, Motorola released a patch for these phones that locked the bootloader, rendering the phone difficult or impossible to upgrade manually with custom ROMs–so even Android enthusiasts couldn’t upgrade the phones.

Now, this is not necessarily Google’s fault. Google makes the base operating system; it is the responsibility of the individual handset manufacturers to customize it for their phones (which often involves shoveling a lot of crapware and garbage programs onto the phone) and then release it for their hardware. Google has done little to encourage manufacturers to backport Android, nor to get manufacturers to offer a consistent user experience with software updates, instead leaving the device manufacturers free to do pretty much as they choose except actually fork Android themselves…which has led to what developers call “platform fragmentation” and to what Motorola Electrify, Photon and Atrix users call things I shan’t repeat in a blog as family-friendly as this one.

But what of the operating system itself?

Well, it’s a mixed bag of mess.

When I first got my Android phone, I noted how the user interface seemed to have been designed by throwing a box of buttons and dialogs and menus over one’s shoulder and then wired up wherever they hit. System settings were scattered in three different places, without it necessarily being obvious where you might find any particular setting. Functionality was duplicated in different places. The Menu button is a mess; it’s filled with whatever the programmer couldn’t find a better place for, with little thought to good UI design.

Android is built on Linux, an operating system that has a great future on the desktop ahead of it, and always will. The Year of Linux on the Desktop was 2000 was 2002 was 2005 was 2008 was 2009 was 2012 will be 2013. Desktop aside, Linux has been a popular server choice for a very long time, because one thing Linux genuinely has going for it is rock-solid reliability. When I was working in Atlanta, I had a Linux Gentoo server that had accumulated well over two years’ continuous uptime and was shut down only because it needed to be moved.

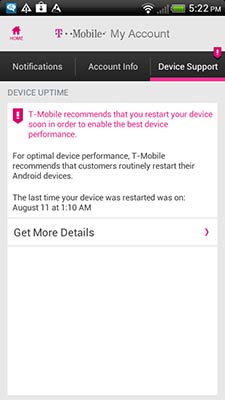

So it is somewhat consternating that Linux on cell phones seems rather fragile.

So fragile, in fact, that my HTC Sensation would pop up a “New T-Mobile Service Notice” alert every week, reminding me to restart the phone. Even the network operators, it would seem, have little confidence in Android’s stability.

It’s a bit disappointing that the one thing I most like about Linux seems absent from Android. Again, though, this might not be Google’s fault directly; the handset makers and network operators do this to themselves, by taking Android and packaging it up with a bunch of craplets of spotty reliability.

One of the things that it is really, really important to be aware of in the Android ecosystem is the way the money flows. You, as a cell phone owner, are not Google’s customer. Google’s customer is the handset manufacturer. You, as as a cell phone owner, are not the handset manufacturer’s customer. The handset manufacturer’s customer is the network operator. You are the network operator’s customer–but you are not the network operator’s only customer.

Because of this, the handset maker and the network operator will seek additional revenue streams whenever they can. If someone offers HTC money to bundle some crap app on their phones, HTC will do it. If T-Mobile decides it can get more revenue by bundling its own or someone else’s crap app on your phone, it will.

Not only are you not the customer, at some points along the chain–for the purposes of Google ad revenue, say–you are the product being sold. Whenever you hear people talking about “freedom” or “openness” in the Android ecosystem, never forget that.

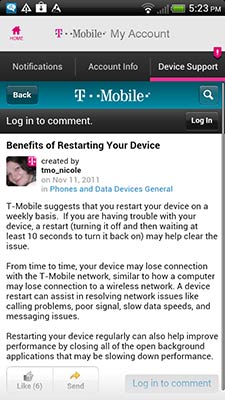

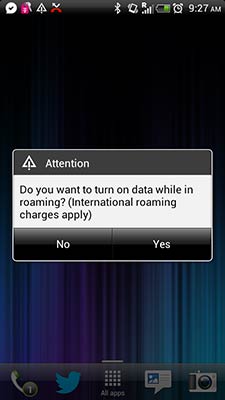

I sometimes travel outside the US, mainly to Canada these days. When I do that, my phone really, really, really wants me to turn on data roaming.

There are reasons for that. When you roam, especially internationally, the telcos charge rates for data that would make a Mafia loan shark blush. So Android agreeably nudges you to turn on data roaming, and here’s kind of a sticking point…

Even if you’re connected to the Internet via wifi.

It pops up an alert constantly, and by “constantly” I really do mean constantly. Even when you have wifi access, it pops up every time you switch applications, every time you unlock the phone, and about every twenty minutes when you aren’t using the phone.

Just think of it as Google’s way to help the telcos tap your ass that revenue stream.

This multiple-revenue-streams-from-multiple-customers model has implications, not only for the economics of the ecosystem, but for the reliability of your phone as well. And even for the battery life of your phone.

Take HTC phones on T-Mobile (please!). They come shoveled–err, “bundled”–with an astonishing array of crap. HTC’s mediocre Facebook app. HTC Peep, HTC’s much-worse-than-mediocre Twitter client. Slacker Radio, a client for a B-list Internet radio station.

The presence of all the various crapware that comes preloaded on most Android phones, plus the fact that Android apps don’t quit when they lose focus, generally means that a task manager app is a necessary addition to any Android system…which is fine for the computer literate, but less optimal for folks who aren’t so computer savvy.

And it doesn’t always help.

For example, Slacker Radio on my Sensation insists on running all the time at startup, whether I want it to or not:

Killing it with the task manager never works. Within ten minutes after being killed, it somehow respawns, like a zombie in a George Ramero movie, shambling after you no matter how many times you shoot it:

The App Manager in the Android control panel has a function to disable an app entirely, even if it’s set to launch at startup. For reasons I was never able to understand, this did not work with Slacker. It was always there. Always. There. It. Never. Goes. Away. You. Can’t. Hide. From. It.

Speaking of that “disable app” functionality…

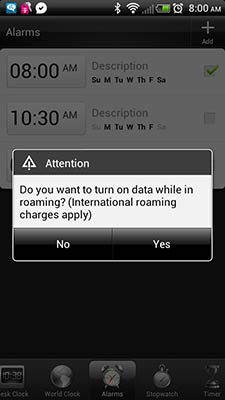

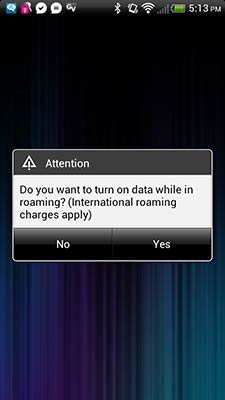

Oh, goddamnit, no, I don’t want to turn on data roaming. Speaking of that “disable app” functionality, use it with care! I soon learned that disabling some bundled apps can have…unfortunate consequences.

Like HTC Peep, for instance. It’s the only Twitter client for smartphones I have yet found that is even worse than the official Twitter client for smartphones. It loads a system service at startup (absent from the Task Killer screenshots above because I have the task killer set not to display system services). If you let it, it will download your Twitter feed.

And download your Twitter feed.

And download your Twitter feed. It does not cache any of the Twitter messages you read; every time you start its user interface, it re-downloads the whole thing again. The result, as you might imagine, is eyewatering amounts of data usage. If you aren’t one of the lucky few who still has a truly unmetered data plan, think twice about letting Peep have your Twitter account information!

Oh, and don’t try to disable it in the application control panel. If you do, the phone’s unlock screen doesn’t work any more, as I discovered to my chagrin. Seriously.

The official Twitter app isn’t much better…

…but at least it isn’t necessary to unlock the damn phone.

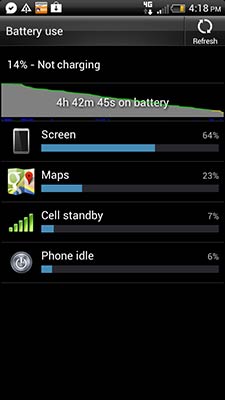

All this crapware does more than eat memory, devour bandwidth, and slow the phone down. It guzzles battery power, too. One of the default Google apps, Google Maps, also starts a service each time the phone boots up, and man, does it hog the battery juice…even if you don’t use Maps at all. (This screen shot, for instance, was taken at a point in time when I hadn’t touched the Maps app in days.)

You will note the battery is nearly exhausted after only four hours and change. I eventually took to killing the Maps service whenever I restarted the phone, which seems to have improved the HTC’s mediocre battery life without actually affecting Maps when I went to use it.

Another place where Android’s lack of a clear and consistent user interface–

AAAAARGH! NO! NO, YOU PATHETIC FUCKING EXCUSE OF A THING, I DO NOT WANT TO TURN ON DATA ROAMING! THAT’S WHY I SAID ‘NO’ THE LAST 167 TIMES YOU ASKED! SO HELP ME, YOU ASK ME ONE MORE TIME AND I WILL TIP YOU STRAIGHT INTO THE NEAREST EMERGENCY INTELLIGENCE INCINERATOR! @$#%%#@!

Sorry, where was I?

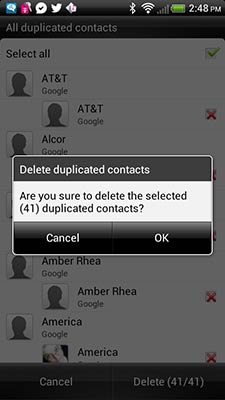

Oh, yes. Another place where Android’s lack of a clear and consistent user interface is its contact management, which is surely one of the more straightforward bits of functionality any smart phone should have.

Android gives you, or perhaps “makes you take responsibility for,” a level of granularity of the inner workings of its contact database that really seems inappropriate.

It makes distinctions between contacts which are stored on your SIM card, contacts which are stored in the Google contact manager (and synced to the Google cloud), and contacts which are stored in other ways. There are, all in all, about half a dozen ways to store contacts–card, Google cloud, T-Mobile cloud, phone memory card. They all look pretty much the same when you’re browsing your contacts, but different ways to store them have different limitations on the type of data that can be stored.

Furthermore, it’s not immediately obvious how and where any particular contact is stored. Things you might think are being synced by Google might not actually be.

And worse, you can’t, as near as I was ever able to tell, export all your contacts at once. Oh, you can export them, all right; Android lets you save them in a .vcf file which you can then bring to another phone or sync with your computer. But you can’t export ALL of them. You have to choose which SET you export: export all the contacts on your SIM card? Export all your Google contacts? Export all your locally-saved-on-the-phone-memory-card contacts?

When I was in getting my second warranty replacement phone, I asked the technician if there was an easy way to take every contact on the phone and save all of them in one export. He said, no, there really isn’t; what he recommended I do was export each group to a different file, then import all those files to my Google contact list, and then finally delete all the duplicates from all the other contact lists.

It worked, but seriously? This is stupid user interface design. It’s a user interface misfeature you might not ever encounter if you always (though luck or choice) save your contacts to the same set, but if for whatever reason you haven’t, God help you.

Yes, I can see why you might want to have separate contact lists, stored and backed up separately. No, that does not excuse the lack of any reasonable way to identify, sort, and merge those contact lists. C’mon, Google engineers, you aren’t even trying.

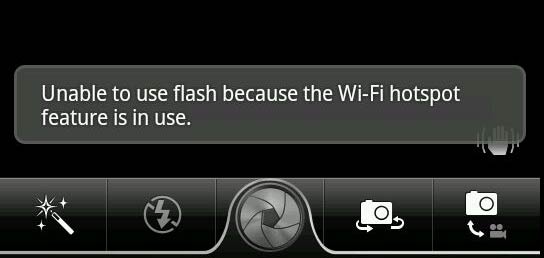

And speaking of brain-dead user interface design, how about this alert?

What the fuck, Google?

Okay, I get it, I get it. WiFi sharing uses a lot of battery power. The flash uses battery power. Android is just looking out for my best interests, trying to save my battery…

…but don’t all the Fandroids carry on about how much better Android is because it doesn’t force you to do what it thinks is best for you, it lets you decide for yourself? Again I say, what the fuck, Google?

So far, I have complained mostly about the visible bits of Android, the user interface failings and design decisions that demonstrate a lack of any sort of rigorous, cohesive approach to UI design.

Unfortunately, the same problems apply to the internals of Android, too.

One early design decision Google made in the first days of Android concerns the way it handles screen redraws. Google intended for Android to be portable to a wide range of phones, from low-end phones to full-featured smartphones, and so Android does not make use of the same level of GPU acceleration that iOS does. Instead, it uses the CPU to perform many drawing tasks.

This has performance and use implications.

User interface drawing occurs in an application’s main execution thread and is handled primarily by the CPU. (Technically speaking, each element on the screen–buttons, widgets, and so on–is rendered by the CPU, then the GPU handles the compositing.) That means that applications will often block while screen redraws are happening. On HTC Sense, for instance, if you put a clock on the home screen and then you start switching between screens, the clock will freeze for as long as your finger is on the screen.

It also means that things like populating a scrolling list is far slower on Android than it is on iOS, even if the Android device has theoretically better specs. Lists are populated by the CPU, and when you scroll through a list, the entire list is redrawn with each pixel it moves. On iOS, the list is treated as a 2D OpenGL surface; as you scroll through it, the GPU is responsible for updating it. Even on smartphones with fast processors, this sometimes causes noticeable UI sluggishness. Worse, if the CPU is interrupted by something else, like updating a background task or doing a memory garbage collect, the UI freezes for an instant.

Each successive version of Android has accelerated more graphics functions. Android 4 is significantly better than Android 2.3 in this regard. User input can still be blocked during CPU activity, and background tasks still don’t update UI elements while a foreground thread is doing so (I was disappointed to note that in Android 4, the clock still freezes when you swap pages in HTC Sense), but Android 4’s graphics performance is way, way, waaaaaaay better than it was in 2.3.

There are still some limitations, though. Because UI updates occur in the main execution thread, even in Android 4, background tasks can still end up being blocked while UI updates are in effect. This actually means there are some screen captures I wanted to show you, but can’t.

One place where Android falls down compared to iOS is in its built-in touch keyboard. Yes, hardcore geeks prefer physical keyboards, and Android was developed by hardcore geeks, which might be part of the reason Android’s touch keyboard is so lackluster.

One problem I had in Android 2.3 that I really, really hoped Android 4 would fix, and was sad to note that it didn’t, is that occasionally the touch keyboard just simply does not work.

Intermittently, usually once or twice a day, I would bring up an app–the SMS messenger, say, or a notepad, or the IMO IM messenger, and I’d start typing. The phone would buzz on each keypress, the key would flash like it does…but nothing would happen. No text would be entered.

And I’d quit the app, and relaunch it, and everything would be fine. Or it wouldn’t, and I’d quit and relaunch the app again, and if it still wasn’t fine, I’d reboot the phone, and force quit Google Maps in the task manager, and everything would be fine.

I tried very hard to get a screen capture of this, but it turns out the screen capture functionality doesn’t work when your finger is on the touch keyboard. As long as your finger is on the keyboard, the main execution thread is busy drawing, and background functions like screen grabs are blocked.

Speaking of the touch keyboard, there’s one place iOS really shines over Android, and that’s telling where your finger is at on the screen.

That’s harder than it sounds. For one, the part of your finger that first makes contact with the screen might not be where you think it is; it’s not always right in the middle of your finger. For another, when your finger touches the screen, it’s not just a single x,y point that’s being activated. Your finger is big–when you have a high-resolution screen, it’s bigger than you think. A whole lot of area on the touch screen is being activated.

So a lot more deep programming voodoo goes on behind the scenes to figure out where you intended to touch than you might think.

The keys on an iPhone touch keyboard are physically smaller on the screen than they are on an Android screen, and Android screens are often bigger than iOS screens, too. You’d think that would mean it’s easier to type on an Android phone than an iPhone.

And you’d be wrong. I have found, consistently and repeatably, that my typing accuracy is much better on an iPhone than an Android phone, even when the Android phone has a bigger screen and a bigger keyboard. (One of my friends complains that I have fewer hilarious typos and bizarre autocorrects in my text messages now, since I switched back to the iPhone.)

The deep voodoo in iOS appears to be better than the deep voodoo in Android, and yes, I calibrated my touch screen in Android.

Now, you can get third-party keyboards on Android that are much better. The Swiftkey keyboard for Android is awesome, and I love it. It’s a lot more sophisticated than any other keyboard I’ve tried, no question.

But goddamnit, here’s the thing…if you pay hundreds of dollars for a smart phone with a built-in touch keyboard, you shouldn’t HAVE to buy a third-party keyboard to get good results. Yes, they exist, but that does not excuse the pathetic performance of the stock Android keyboard! It’s like saying “Well, this new operating system isn’t very good at loading files, but that’s not a problem because you can buy a third-party file loader.” The user Should. Not. Have. To. Do. This.

And even if you do buy it, you’re still not paying for the amount of R&D that went into it. It’s a losing proposition for the developer AND for the users.

My new iPhone included iOS 6, which feels much more refined than Android on almost every level.

I would be remiss, however, if I didn’t mention what a lot of folks see at the Achille’s heel of iOS: its Maps app.

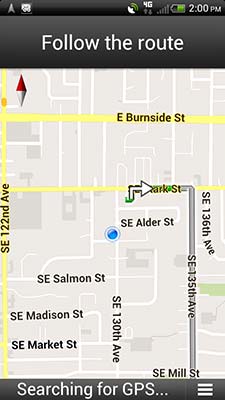

Early iPhones used Google Maps, a solid piece of work that lacked some basic functionality, such as turn-by-turn directions. When I moved to Android, I wrote about how the Maps app in Android was head, shoulders, torso, and kneecaps above the Maps app in iOS, and it was one of the best things about Android.

And then Android 4 came along.

I don’t know what happened to Maps in Android 4. Maybe it’s just a problem on the Sensation. Maybe it’s an issue where the power manager is changing the processor clock speed and Maps doesn’t notice. I don’t know.

But in Android 4, the cheery synthesized female voice that the turn-by-turn directions used got a little…weird.

I mean, it always was weird; you should hear how it pronounces “Caesar E. Chavez Blvd” (something Maps in iOS 6 pronounces just fine, actually). But it got weirder, in that it would alternate between dragging like a record player (does anyone remember those?) with a bad motor and then suddenly speeding up until it sounded like it was snorting a mixture of helium and crystal meth.

It was a bit disconcerting: “In two hundred feet, turn llllllllllleeeeeeeeeeffffffffftttttttt oooooooooonnnnnnnnn twwwwwwwwwwwwweeeeeeeeeeennnnnnnnttttyyyyyyyy–SECONDAVENUEANDTHENTURNRIGHT!” There was never a rhyme or reason to it; it never happened consistently on certain words or in certain places.

Now, Maps on iOS has been slammed all over Hell and back by the Internetverse. Any mapping program is going to have glitches (Google places a street that a friend of mine lives on about two and a half miles from where it actually is, in the middle of an empty field), but iOS apparently has a whole lot of very silly errors.

I say “apparently” because I haven’t personally encountered any yet, knock on data.

It was perhaps inevitable that Apple should eventually roll their own app (if by “roll their own” you mean “buy map data from Tom Tom”), because Google refused to license turn-by-turn mapping to Apple, so as to create a product differentiation point to make bloggers like me say things like “Wow, Google’s Android Map app sure is better than the one on iOS!” That was a strategy that couldn’t last forever, and Google should have known that, but… *shrug* Whatever. Since Google lost the contract to supply the Maps app to Apple, they took a hit larger than their total Android revenue; if they want to piss it away because they didn’t want Apple to have turn-by-turn directions, I think they really couldn’t have expected anything else.

In part 3 of this thing, I’ll talk about T-Mobile, and how they’re so hopelessly dysfunctional as a telecommunication provider they make the North Korean government look like a model of efficiency.

Like this:

Like Loading...

But it isn’t just the grandeur of the natural world. Beauty lurks in every corner. It hides in a tumbler filled with colored glass stones on a restaurant table.

But it isn’t just the grandeur of the natural world. Beauty lurks in every corner. It hides in a tumbler filled with colored glass stones on a restaurant table.

Premise 1 is a very common one. “There is no morality without God” is a notion those of us who aren’t religious never cease to be tired of hearing. There are a number of significant problems with this idea (whose God? Which set of moral values? What if those moral values–“thou shalt not suffer a witch to live,” say, or “if a man also lie with mankind, as he lieth with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination: they shall surely be put to death,” or “whatsoever hath no fins nor scales in the waters, that shall be an abomination unto you”–cause you to behave reprehensibly to other people? What is the purpose of morality, if not to tell us how to be more excellent to one another rather than less?), but its chief difficulty lies in what it says about the nature of humankind.

Premise 1 is a very common one. “There is no morality without God” is a notion those of us who aren’t religious never cease to be tired of hearing. There are a number of significant problems with this idea (whose God? Which set of moral values? What if those moral values–“thou shalt not suffer a witch to live,” say, or “if a man also lie with mankind, as he lieth with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination: they shall surely be put to death,” or “whatsoever hath no fins nor scales in the waters, that shall be an abomination unto you”–cause you to behave reprehensibly to other people? What is the purpose of morality, if not to tell us how to be more excellent to one another rather than less?), but its chief difficulty lies in what it says about the nature of humankind.

The Culture novels are interesting to me because they are imagination writ large. Conventional science fiction, whether it’s the cyberpunk dystopia of William Gibson or the bland, banal sterility of (God help us) Star Trek, imagines a world that’s quite recognizable to us….or at least to those of us who are white 20th-century Westerners. (It’s always bugged me that the alien races in Star Trek are not really very alien at all; they are more like conventional middle-class white Americans than even, say, Japanese society is, and way less alien than the Serra do Sol tribe of the Amazon basin.) They imagine a future that’s pretty much the same as the present, only more so; “Bones” McCoy, a physician, talks about how death at the ripe old age of 80 is part of Nature’s plan, as he rides around in a spaceship made by welding plates of steel together.

The Culture novels are interesting to me because they are imagination writ large. Conventional science fiction, whether it’s the cyberpunk dystopia of William Gibson or the bland, banal sterility of (God help us) Star Trek, imagines a world that’s quite recognizable to us….or at least to those of us who are white 20th-century Westerners. (It’s always bugged me that the alien races in Star Trek are not really very alien at all; they are more like conventional middle-class white Americans than even, say, Japanese society is, and way less alien than the Serra do Sol tribe of the Amazon basin.) They imagine a future that’s pretty much the same as the present, only more so; “Bones” McCoy, a physician, talks about how death at the ripe old age of 80 is part of Nature’s plan, as he rides around in a spaceship made by welding plates of steel together.

But I wonder…would a post-scarcity society necessarily be Utopian?

But I wonder…would a post-scarcity society necessarily be Utopian? One such society might be the Aztec empire, which spread through the central parts of modern-day Mexico during the 14th century. The Aztecs were technologically sophisticated and built a sprawling empire based on a combination of trade, military might, and tribute.

One such society might be the Aztec empire, which spread through the central parts of modern-day Mexico during the 14th century. The Aztecs were technologically sophisticated and built a sprawling empire based on a combination of trade, military might, and tribute.