I’m a little surprised, whenever I think about it, that human beings were able to successfully treat, much less cure, any disease whatsoever prior to…oh, I don’t know, about 1977 or so.

Seriously, whenever one picks up a history book or (God forbid) a book on medical technology, it seems that before the advent of Star Wars all we had were superstition, stone knives, and dried tiger penises. In fact, even to this day, many people’s sum total understanding of basic biology scarcely extends beyond stone knives and dried tiger penises–but I didn’t come here to talk about the alt-medicine crowd.

Instead, I came here to talk about Boston. Err, not Boston itself, you understand, but our journey toward that fabled (and by now near-mythical) Xanadu, where my friend Claire had been accepted to a university or a Thunderdome or something. By this point, it was all getting a bit blurry, what with the heat and the prairie dogs and the Jesus of Wheat and all.

When we next set out, with Erica driving and me trying with only modest success to deal with a client’s crisis of some sort about something or other, the temperature was already nudging toward the triple digits. Frankly, I’m sometimes a bit surprised that any human being successfully survived summer in the Midwest prior to the invention of air conditioning. We had determined days before to make a stop at the Glore Psychiatric Museum in St. Joseph, Missouri. We had a book which called it one of the 50 “most unusual museums in the United States.” I’m not quite sure who made that list or on what criteria it was based, but the Museum of Spam (the quasi-meat product, not the email full of Nigerian princes and penis pills) is on the list, and that’s good enough for me.

The Glore Psychiatric Museum is housed in what’s left of Missouri State Lunatic Asylum No. 2–yep, that was its official name. Now, I’ve seen a number of Hollywood films involving a small number of friends who happen to be traveling alone across the country. All of them recommend stopping for a time in the ruins of an old lunatic asylum, so stop we did.

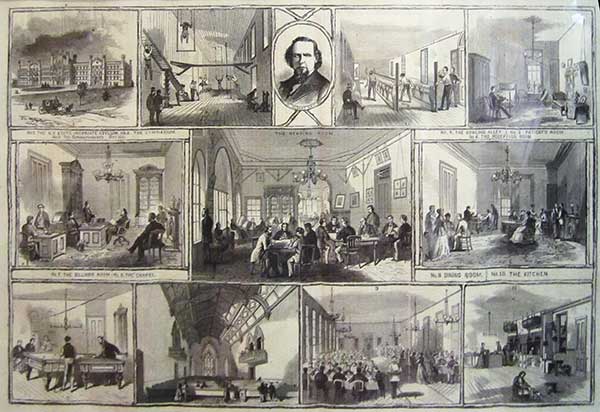

The first thing one sees upon entering the museum is this old newspaper illustration, apparently dating back to the time of the asylum’s founding, which depicts life in an insane asylum as a rather proper Victorian affair replete with formal tea and, I don’t know, Badminton games or something. “I say, old chap, after our noonday repast, would you fancy a stroll through the park, followed by a rousing cricket match?” “That sounds delightful, dear fellow, but I rather think we should postpone the afternoon meal until after our sport.” “After our sport? I say, are you mad?” “Quite so, old sport!”

We ventured farther in, where we were met by a cheerful gentleman who assured us that no psychotic, supernatural offspring of crazed serial killers bent on bloody vengeance had been seen ’round the grounds in almost a fortnight, so we were confident that our stay would be pleasant and free of the bother one normally can expect from such things.

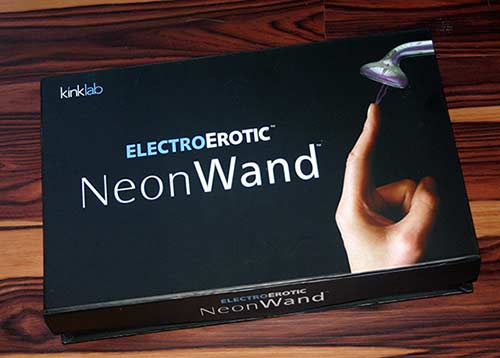

It doesn’t take very long to realize that anyone unwise enough to be crazy prior to the age of Pac-Man was in for rather sorry treatment at the hands of his fellow man. The museum has a floor full of devices which had previously been used to “treat” mental illness, and to my (admittedly untrained) eye, rather a lot of them looked indistinguishable from the sorts of devices the Inquisitors might use. Take these gadgets, for example:

The chair on the left was used to calm patients by restricting their mobility. Sometimes, apparently, for weeks. The gizmo on the left was designed to confine a person in a very small box which would then be spun ’round at high speed until the unfortunate occupant passed out or threw up, or both–presumably on the premise that a vomiting mental patient is better than a mental patient who…um, isn’t vomiting, or, err, something. The precise details of the therapeutic modality are beyond my grasp of the art.

And the definitions of “mentally ill” were as all over the map as the treatments. In ages past, an unmarried woman who wanted children might be confined to an asylum, as might a married woman who didn’t. (True fact: the dude who invented the diagnoses of “nymphomania” included diagnostic criteria such as a fondness for chocolate and a penchant for reading works of fiction, I swear I am not making this up.)

It rather seems, all in all, that the considered opinion of the entire medical establishment over a very long span of time was that the mentally ill were just being stubborn, and merely needed a few nasty knocks about the head to get them to cut it out. This seems to your humble scribe rather like saying a legless man is simply being lazy, and all he needs is a good swift kick in the pants to get him on his feet again…though I didn’t come here to talk about the Republican party, either.

The general theme of “knock them about a bit ’til they learn to cut it out” as a treatment modality for cognitive and emotional impairment continues through quite a lot of the medical equipment on display:

Some of the items in their collection would look, I have to say, right at home here in my dungeon, and I wouldn’t mind building something like that long cage on the left…but only for people who are of sound and willing mind. I may be a mad scientist, but I’m not, well, crazy, you know? At least not like the folks who actually thought these things would do some good.

A number of other displays commemorated the sometimes colorful and occasionally fatal eccentricities of a few of the hospital’s more outstanding patients. Take this one, for example, which is just kind of weird until you know what it is, at which point it becomes weird and gross.

This bizarre work of art was made by hospital staff, not by a patient, out of the materials found in a patient’s…err, stomach. The patient in question, you see, had what would today be called obsessive-compulsive disorder, but the particular manifestation of her obsession lay in eating any little bits of sharp pointy metal things that she could get her hands on. Which, as you might expect, eventually killed her.

See? Weird and gross. I did try to warn you.

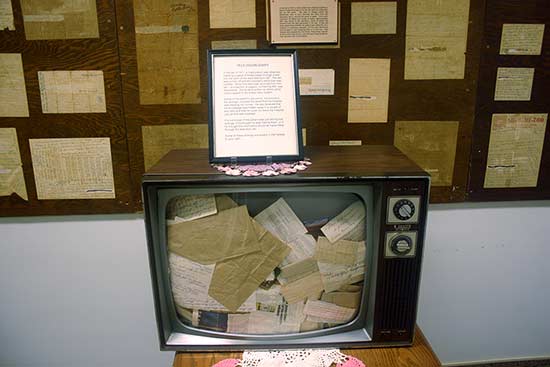

This guy, on the other hand, was straight out of the X-Files:

The story, as near as I can remember it, is that there was this dude who was completely convinced he was sane, while all the people around him thought that he was stark raving mad. He was utterly convinced that there were railroad box cars containing evidence of his sanity being kept at an undisclosed location, and he wrote about them obsessively. Somewhere along the way, he also became convinced that the television set in his room contained a secret mechanism by which he could send messages to the vague and sinister forces hiding the box cars from him, or perhaps to agents opposing those sinister forces (it’s not entirely clear to your humble scribe) so he wrote long, rambling, incoherent letters about box car numbers and train routes and railway schedules and stuff, or something, and tucked them inside the television set, until it eventually quit working.

Which, I reckon, wasn’t actually the outcome he had hoped for. It’s bad enough when a secret conspiracy has plotted to conceal evidence vital to your sanity in railway cars; it’s even worse when you can’t watch next week’s Gunsmoke on television.

This next bit is a tiny section of a huuuuuge piece of embroidery, created by hand by a patient on what I believe to be a hospital bedsheet.

We puzzled over it for quite a while. Reading it is rather like trying to track a coherent thought through a untrodden jungle the way a traditional Chinese doctor might track a tiger across the savannah, following its telltale traces in the slightest disturbance of underbrush, before shooting it in the head and drying out its penis to make phony aphrodisiacs that are sold in small glass vials from musty shops whose owners don’t really give a toss about the extinction of a noble species for the sake of superstition…but I digress.

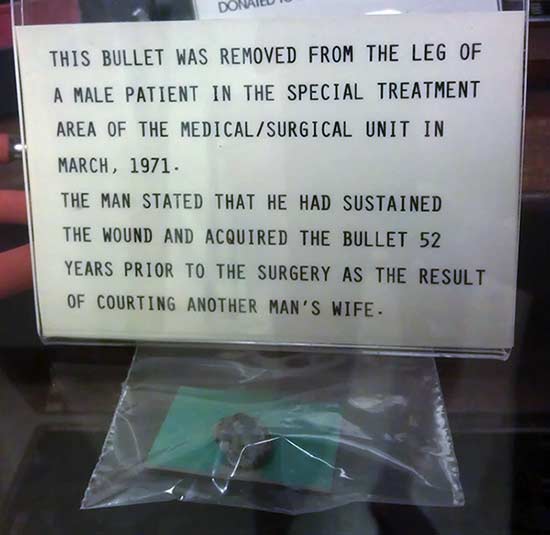

This display one was one of my favorites.

One should not court another man’s wife if one wishes to avoid a sticky fate. You heard it here first.

The basement of the old hospital, where we ended up after we decided to separate and explore the ancient lunatic asylum separately just as Hollywood has taught us to do, bore a large steel door with these markings:

It is unclear to your humble scribe exactly what sort of disaster supplies one keeps in the morgue, or indeed what eventuality those supplies are intended to ward against. I can only imagine it’s not a zombie-related disaster, as keeping one’s zombie-related disaster supplies in the same location as the corpses of the newly dead is likely to result in a certain inconvenience.

We fled the museum through the gift shop, where many commemorative items were available for sale (“Relive the experience again and again!”), and then were once again on our way to Shangri-La. There were by now only a couple of adventures left before our encounter with the Guatemalans and our renewed appreciation to the full fury of Nature’s watery wrath, but those tales will need to wait for another telling.

Displays mounted on walls, instead of displays being walls. Handheld cell phones with 3D screens, instead of completely virtualized input and output (say, contact lenses with 3D displays). “Computing devices” being distinct entities from other devices. Cars that have displays embedded in their windows, rather than cars whose windows–or paint jobs!–are displays. And everywhere swipe, swipe, push, and swipe.

Displays mounted on walls, instead of displays being walls. Handheld cell phones with 3D screens, instead of completely virtualized input and output (say, contact lenses with 3D displays). “Computing devices” being distinct entities from other devices. Cars that have displays embedded in their windows, rather than cars whose windows–or paint jobs!–are displays. And everywhere swipe, swipe, push, and swipe.

There’s a p value associated with any experiment. For example if someone wanted to show that watching Richard Simmons on television caused birth defects, he might take two groups of pregnant ring-tailed lemurs and put them in front of two different TV sets, one of them showing Richard Simmons reruns and one of them showing reruns of Law & Order, to see if any of the lemurs had pups that were missing legs or had eyes in unlikely places or something.

There’s a p value associated with any experiment. For example if someone wanted to show that watching Richard Simmons on television caused birth defects, he might take two groups of pregnant ring-tailed lemurs and put them in front of two different TV sets, one of them showing Richard Simmons reruns and one of them showing reruns of Law & Order, to see if any of the lemurs had pups that were missing legs or had eyes in unlikely places or something.