This is part 1 of a series about GMO foods. The previous two parts of this series can be found at GMohno! Part 0: What It Is, which talks about what GMO actually means; and GMohno! Part 0.5: How to Tell when you’re Being Emotionally Manipulated, which talks about some of the techniques of emotional manipulation frequently encountered in any discussion about GMOs.

The remaining parts of this series are this one, which looks at the legal, political, and social consequences of GMOs; the next one, which addresses health and safety issues; and the third, which looks at the “evil corporate malfeasance” arguments.

So, let’s begin!

Imagine this scenario: You’re a farmer. Your parents and grandparents were farmers. Your family has worked the same field with the same techniques for generations.

But now, you’re offered new seeds. These new seeds, you’re told, will make your farm more productive. But there’s a catch. The seeds are patented by a seed company; in order to plant them, you must pay a patent licensing fee. Also, if you plant these seeds and then, at harvest, try to keep some of the seeds the plants produce so you can plant them next year, the seeds you save won’t produce well. You will have to buy new seeds from the seed company next year, and the year after that, and the year after that.

Is this the way big agribusiness uses GMO technology to control your farm and make more profit from you? Well, maybe.

It might also be the consequence of buying patented organic hybrid seeds for an organic farm.

In conversations about GMOs, it’s very common for someone to raise the point that GMO foods are often protected by patent law. This patent protection means that farmers must pay patent licensing royalties to the seed producer in order to plant the seeds. Many seed companies also prohibit saving and re-planting seeds, which can create a dependence on the seed company for annual resupplies of seed stock.

This might seem to be a pretty compelling argument against GMOs, particularly in the developing world. But it ignores some information, and it’s based on misconceptions and ignorance about plant patents and seed licensing.

Let’s talk first about the economics of using patented seeds. In the US and Western countries, the genes of a plant are often the limiting factor on the maximum yield per acre. Modern Western farms are heavily mechanized and use irrigation, fertilizers and pest management to provide nearly optimal growing conditions for the plants, so the limiting factor on production is how good the plants themselves are.

Anti-GMO activists often talk about seed companies such as Monsanto “forcing” farmers into seed purchase and non-reuse contracts. This argument infantilizes farmers; farmers have a choice, and are not forced to use GMO seed if they don’t want to. There’s no contract that says “you have to buy our seed every year from now on.” The contracts instead say “if you use this seed, you can’t save seeds for next season and you agree to pay a per-acre fee to license the patent.” If the deal isn’t beneficial to farmers, next year they choose a different seed; there’s quite a lot out there to choose from.

Most US farmers–and I’ve talked to quite a few–really don’t mind not saving seeds. Indeed, they generally don’t want to save seeds. For one thing, on a modern US farm, the cost of seed is a very small part of the yearly cost of a farm; it might typically be anywhere from 5% to 7% of a farmer’s annual expenses, depending on the type of crop and the type of seed. In exchange, the farmer is getting seeds that have been dried and treated to maximize germination rates. It’s important to consider that saving seed is not free; the seed, once it’s saved, must be processed, dried, and stored, and the storage not only isn’t free but also brings pest management issues with it. On large-scale Western farms, the cost of seeds is worth it. It saves work, increases germination, and in many cases comes with written guarantees from the seed company.

Similarly, licensing fees for GMO seeds are modest. They have to be, or the farmers wouldn’t use them. For example, Monsanto’s GMO soy license fees are typically about $17 an acre. DuPont charges about $40 an acre for GMO alfalfa. On average, DuPont alfalfa produces about a thousand pounds more per year per acre of alfalfa over similar non-GMO alfalfa varieties. As of mid-year this year, alfalfa was selling for about $280 a ton, meaning that thousand pounds returns $120 per acre per year to the farmer, three times the DuPont licensing fee.

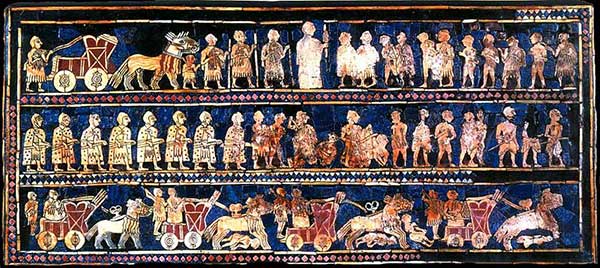

If this is what your farm looks like, patents aren’t a big deal

So in the US, where farm yield is bound by plant genetics and the licensing fees for GMO patents are more than offset by increasing yields, the economics of plant patents makes sense.

But what about in developing nations, where farms may not be running close to the theoretical maximum yields, and plant patent restrictions are more costly in terms of total percentage of outlays on farming?

That’s a more complicated issue, and addressing it will require a brief digression into a technique often used to lie with statistics: the problem of excluded information.

“But patents!” people say. “We shouldn’t be allowing seed companies to patent GMO seeds. Seed patents give corporations control over our food supply!”

I’v heard a lot of folks say this. I think there’s room to debate whether or not basic food stock should be patentable.

But here’s the missing bit: Organic and conventional crops are also patented. I never really understood the objection about GMO crops being protected by patents until I finally figured out that most people simply don’t know that plant patents apply to all kinds of plants, not just GMOs.

The first plant patents were issued in the 1800s. Natural mutations of crops can be patented. So can hybrids. Plants created by mutagenesis can be patented.

There is an excellent overview on the Johnny Seed Company’s Web site that talks about plant patents, which I highly recommend reading.

This is an example of the problem of excluded information. When a person says “GMO seeds are bad because they are patented and patenting seeds gives the seed companies too much power,” that person is, intentionally or unintentionally, excluding information that undermines the argument: conventional, hybrid, and organic seeds are also patented. When you include this information, the argument against GMO seeds becomes far less compelling.

The argument that GMO seeds often can’t be saved also rests on excluded information. Most folks may not be aware that hybrid seeds also can’t be saved.

A hybrid seed is a seed from two different plant lines whose genetics are stable enough that they produce a particular trait generation after generation. Let’s say, for hypothetical example, that you have two lines of some fruit. One line is highly resistant to drought, and survives well with little water…but it produces small, bitter fruit. The other produces plump, tasty fruit, but is fragile; it dies without lots of water.

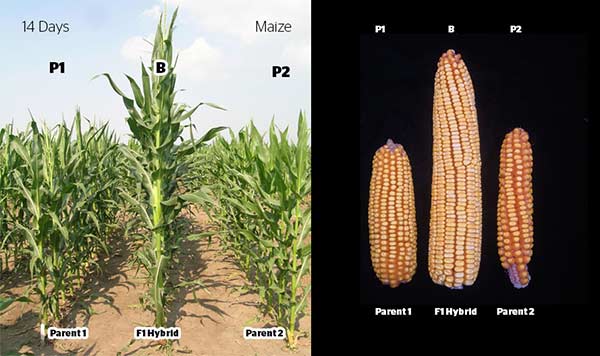

It may be possible to cross-pollinate these two lines and get something that produces tasty fruit but also is quite hardy. This is an “F1 cross“–a first-generation cross between two lines that tend to consistently express the same trait.

The problem is the desired qualities of the hybrid may not be stable. That is, if you save the seeds from the F1 cross and re-plant them, you may end up with only half your plants able to resist drought, and only half your plants producing tasty fruit…so only a quarter of your crop has the traits you want, robustness and good fruit. The characteristics of a hybrid are not necessarily stable, and only the first generation may have the traits you want! If you want to be sure to get both traits, you have to go back to your original two lines and cross them again. Only the F1 crosses will consistently have both.

That means the seed companies that produced the cross must maintain fields of the original robust but inedible variety and the fragile but tasty variety, so they can go back to those lines and hybridize them each year. That means farmers who want to use that hybrid must buy new seed each year. They’re legally allowed to save seed, if they choose to–but the seed they save may not be any good! Hence the example that started this article–a farmer buying hybrid seeds but not being able to save seeds from his harvest. Hybrid seeds can be patented, and hybrid seeds generally can’t be saved.

So the “but patents!” and “but saving seeds!” arguments both rest on missing information: non-GMO crops are also patented, and non-GMO crops also prevent farmers from saving seeds.

In extreme cases, missing information in an argument can actually lead to a conclusion that is exactly the opposite of the truth. That’s why it’s important to evaluate any claim in the context of the environment in which the claim is made.

For example, a couple of years ago there was a surge of news reports of suicides in the Foxconn factories where Dell laptops, Apple iPhones, Microsoft mice, and other consumer electronics are made. People blamed poor working conditions and long hours for causing suicides among factory workers.

What’s the missing information in these claims? We don’t know if people at Foxconn factories are committing suicide at high rates because we don’t know the normal rates of suicide for the areas where the factories are located.

The Foxconn factories employ about 400,000 people. In any group of 400,000 people, there will be some incidence of suicide.

The base rate of suicide in China is 7.9 suicides per 100,000 people per year. The base rate of suicide among Foxconn’s employees is 14 people per year, or about 3.5 suicides per 100,000 people per year. That is, the rate of suicide at Foxconn factories is unusually low–Foxconn employees are less likely, not more likely, to kill themselves. In isolation, “14 suicides at this factory!” sounds high; in context, the reverse is true. (By way of comparison, the base rate of suicide in the United States is 12 suicides per 100,000 people per year.)

An argument made by anti-GMO activists follows this exact model. Many folks have claimed that farmer suicides in India surged when GMO cotton (specifically, Bt cotton, a variant resistant to insect pests) was introduced. In fact, the rate of suicide among farmers in India has been flat for decades and showed no measurable increase after the introduction of Bt cotton. The reports linking GMO cotton to farmer suicide relied on omitted information: the base rate of suicide before the introduction of Bt cotton.

So back to the issue of farms in the developing world. It’s a complicated one, and there are a lot of factors at play…which virtually guarantees that there will be a lot of arguments on the Internet that distort and oversimplify the issues to the point of absurdity.

Is it advantageous for farmers in the developing world to use GMO crops? It depends on the kind of farm, the kind of crop, the place, and a lot more.

White Westerners tend to have a view of the developing world that’s both overly homogenized and overly primitive. When we think of a farm in the developing world, a lot of people probably have a mental image that looks something like this:

On the other hand, we tend to think First World farms look more like this:

In fact, that first picture is from Oregon; the second is from Africa. The reality isn’t as simple as the pictures we have in our head.

When pro-GMO folks say “GMOs are good for the developing world” and anti-GMO activists say “GMOs are terrible for Third World farmers,” they’re both wrong, or both right, depending on which specific farm in which specific part of the developing world you’re talking about.

It also depends on which specific GMO crop you’re talking about. You see, there’s yet another piece of missing information in the “GMOs are bad for farmers because of patents” argument: Not all GMOs are patented.

Plant patents are complicated. Some plants that are not GMO are protected by patents. Some GMOs are not patented. Some GMO licensing terms forbid saving seeds. Some organic hybrid crops prevent saving seeds. Some GMO crops permit saving seeds.

For example, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation finances research and development on GM crops, and any GM technology financed by their foundation must allow farmers to save seeds (note: link is a PDF).

Is it beneficial for farmers in developing countries to plant GM crop? If the farm’s productivity is bound by plant genetics, or the farm is facing a specific problem (for example, poor water or pests) for which a GM-resistant crop exists, then probably yes, depending on the cost and licensing terms, if any, of the GM crop. If productivity isn’t bound by plant genetics and there’s not a compelling reason to use a particular GM variety, then maybe not. That’s one of the key points to remember about GM food: it’s not a cure-all or a magic technology. It’s simply one tool among many in the toolkit. It’s a powerful tool, but not the only tool…and it’s just as silly to think it will solve all the world’s problems as it is to think we shouldn’t ever use it.

So let’s talk about Golden Rice.

This is golden rice. It’s a strain of GMO rice that has a gene to produce beta carotene, which is used by the body to produce Vitamin A. In parts of the world where rice is a staple crop, vitamin A deficiency is a leading source of blindness and death.

Golden rice was not invented by a huge multinational corporation; it was developed by university research supported by a charitable grant. It is not encumbered by patent restrictions; it is public-domain and open-source, freely available to whoever wants it. It requires few pesticides, reducing pesticide exposure by farmers who plant it. And yet, distribution of golden rice has been effectively blocked by anti-GMO activists–primarily wealthy Westerners who don’t have to contend with vitamin deficiency–who have destroyed fields and worked hard to create fear and doubt around it. According to an article published in Environment and Development Economics, “The economic power of the Golden Rice opposition,” the fact that golden rice has not been distributed has has cost 1,424,000 life years since 2002, the year it was, arguably, first ready for commercial planting. This accounts not only for death but for loss of life due to debilitating disease…and, most tragically, the majority of human beings affected have been children.

This is one of the most insidious costs of irrational hysteria. When people fear vaccination, it’s most often children who are sickened or killed. With fear of GMOs, it’s most often children who suffer.

The people who oppose GMOs rarely seem to consider the human cost, and even when they do, it tends to be in a shallow and superficial way. (On one online forum I read, an opponent of golden rice said, and I quote, “why can’t those people just plant carrots?”) Golden rice is intended to be used in parts of the world where rice is already a staple crop. It’s resistant to flooding (which carrots aren’t), it can be used as a staple food (which carrots can’t), it requires no new investment in infrastructure or farming technology (which carrots don’t). It is, in fact, precisely the kind of solution that self-described “environmentalists” claim to want: openly available, not controlled by big for-profit Western corporations, able to be used in farms that already exist, and without creating reliance on Western companies.

There is often an irony in movements based on fear. When environmental activists succeeded in creating widespread fear of nuclear power, power utilities started investing in more coal-fired plants, which are far more dangerous. Coal kills about 10,000 people a year in the United States, mostly from complications from air pollution. In China, where coal is less regulated and even more widespread, coal kills about 300,000 a year. And coal power is, of course, a huge source of greenhouse gas. So in creating fear of nuclear power, environmentalists pushed the world to greater use of coal, which has killed far more people than even the worst-case nuclear power scenarios, and has created a global threat. If every coal plant were replaced with a nuclear plant, and as a result there was a Chernobyl-sized disaster every six months, nuclear would STILL kill fewer people than coal! Opposition to nuclear power created exactly the opposite of what the opponents claim to have wanted.

With GMOs, the reactionary opposition to GM food has, in the case of golden rice, created exactly what the activists claim they want to avoid: greater dependence on Westerners in the developing world.

UNICEF distributes vitamin A to children in need. In 2012, they celebrated a milestone: reaching 70% of the kids in the developing world who would otherwise have suffered from vitamin A deficiencies. It’s a commendable achievement, but when we consider the billions of people who live in developing nations, I’m not sure a C+ grade is sufficient. And aid organizations distributing vitamin A pills doesn’t help ensure food security or sovereignty. What’s the endgame, a never-ending program of aid distribution?

So what are the objections to golden rice? Well, here’s a sample:

If you read Part 0.5 of this essay series, you’ll probably be able to spot the various types of emotional manipulation going on in this argument. The argument doesn’t make sense on a number of levels (Monsanto doesn’t have anything to do with golden rice, golden rice has no magical powers to ‘contaminate’ any other rice strain, farmers can make choices about whether or not to grow it, and so on), but ultimately those shortcomings aren’t relevant because information, by itself, almost never changes attitudes. The objection to golden rice is primary emotional; knocking down the objections is as unlikely to change ideas as farting into a hurricane is to change the trajectory of the storm.

I live in the liberal side of Oregon, where for a while it was trendy to oppose vaccination. The antivax movement is beginning to sputter, thanks in part to measles and whooping cough making a comeback in Oregon. Kids in the antivaxers’ back yards–sometimes, kids in the antivaxers’ families–are dying, and that changes attitudes right quick.

Unfortunately, with vitamin A deficiency, the kids who are dying aren’t in our families or neighborhoods. They’re in far-flung corners of the globe where we as white wealthy Westerners seldom see them. They’re in places where white wealthy Westerners expect kids to die. One death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic. The anti-GMO movement, which predicates many of its arguments on the idea that GM technology will take food sovereignty out of the hands of people in the developing world and concentrate it in the hands of rich Western corporations, play the opposite tune with golden rice: the solution to vitamin A deficiency is not a food that helps provide vitamin A, it’s aid organizations handing out pills, now and tomorrow and next week and next year.

When we consider any technology, whether it’s agricultural or power generation or whatever, we have to look at its risks not in isolation, but in comparison to what the alternatives are. When people opposed nuclear power without thinking of the alternatives, we ended up with coal…and people died. When people reject GM technology out of hand without thinking of the alternatives, we get aid communities celebrating the 70% of kids they are able to supply with vitamin pills…but who’s mourning the 30% they are not?

These are not abstract ideological crusades. They’re real problems with real consequences. We tend to run with what we’re afraid might be true, even when our fears are not substantiated, but decline responsibility for the consequences of our choices. You will never meet those kids; what problem is it of yours?

While we’re on the subject of unintended consequences, let’s talk monoculture.

Let’s backtrack for a moment to the late 1950s. The developing world was on the edge of mass starvation. India, Mexico, and Pakistan could not feed their populations. Norman Borlaug, an American biologist, dedicated his entire life to finding ways to feed a hungry population.

By the time he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, Borlaug was credited, personally, with saving the lives of a billion human beings. In a world that more often remembers people who commit murder on a massive scale, that’s an amazing feat. He spent ten years in Mexico, crossing thousands of wheat varieties to develop a strain of high-yield, disease-resistant wheat. From there he traveled to Pakistan, which was facing a famine so acute that even emergency food aid in the form of millions of tons of US wheat couldn’t feed everyone. In five years, he doubled Pakistan’s food production. By 1974, India became self-sufficient in food, no longer requiring foreign aid to feed its population (something which, just for the record, many of Borlaug’s contemporaries flatly dismissed as ‘impossible’).

Norman Borlaug saved a billion human lives, but there was a downside. The high-yield, resilient, drought and disease resistant crops he developed became very widespread, because they survived and thrived and fed a lot of folks. Now, enormous parts of the world rely on only a handful of crop species for their food.

This is a “monoculture,” a practice of growing a single strain of a single crop on large areas of land. Monocultures can be bred for toughness and resistance to pests, but if a pest or a disease should affect them, the consequences are potentially huge.

The Union of Concerned Scientists has a statement on their Web site that dismisses current large-scale agriculture as “a dead end, a mistaken application to living systems of approaches better suited for making jet fighters and refrigerators.” Which sounds smug and patronizing when you consider that “dead end” saved a billion lives. Oh, but pish-posh, they’re just brown people, right? So it saved a billion Mexicans and Indians and Pakistanis…dead end.

Today, one of the arguments against GMO technology is the “but it will create crop monocultures!” argument. The anti-GMO activist GMO Journal says “Since genetically modified crops (a.k.a. GMOs) reinforce genetic homogeneity and promote large scale monocultures, they contribute to the decline in biodiversity and increase vulnerability of crops to climate change, pests and diseases.”

There’s an incredible, and probably unintentional, irony here.

Monocultures are fragile. Everyone knows this. Everyone has always known this. When you’re faced with a billion human beings dying right now, you (well, if you’re a decent person, anyway) solve that problem first, then deal with solving more far-off problems like crop monocultures. If you think Norman Borlaug shouldn’t have developed his crop strains that saved all those people because you think crop monocultures are a bigger problem than a billion human deaths, you’re a special kind of evil and I don’t want to talk to you.

Now, about GMOs.

As I said, everyone knows crop monocultures are problematic. I think it’s callous in the extreme to dismiss large-scale agriculture as a “dead end” as if the lives of the people it saved don’t matter, but I also think that, yes, monocultures are inherently fragile. They represent a problem that needs to be solved.

Here’s the unintended irony part: The development of GM technology was seen as a way to solve the problem of crop monocultures.

Prior to GM technology, developing new strains of crops was incredibly difficult and labor-intensive. There were two approaches: hybridization (crossing thousands and thousands of strains of plant to look for hybrids that have desirable traits, then back-crossing those to try to get a strain that breeds true) and mutagenesis (taking seeds and bombarding them with chemicals or radiation to deliberately disrupt their DNA, in the hopes that some of the seeds will then by random chance end up with desirable traits…then back-crossing those to try to get a strain that breeds true).

GM technology is precisely targeted. When we find a plant with a gene we want (say, immunity to a plant virus, or drought resistance, or whatever), we can introduce just that gene in a controlled way. We don’t need to do large-scale, random reshuffling of tens or hundreds of thousands of genes. We don’t need massive disruption of DNA in a spray-and-pray fashion. We can get just the strain with just the traits we want.

This was hailed, at first, as a way to custom-tailor specific plant strains to exactly the growing conditions and needs of farmers. No more giving every farmer the exact same strain; farmers could choose from a wide variety of different crop strains with different genes, selecting just the traits they needed. GM technology, in other words, was developed partly as a solution to the problem of monocultures.

Anti-GMO activists complaining that GMOs promote monoculture is a bit like religious Fundamentalists saying that homosexuality MUST be bad, because look at how many gay teenagers commit suicide! The problem is one of their own creation. Fundamentalists start with the idea that homosexuality is bad, and bully, harass, and intimidate kids based on real or perceived sexual orientation…then when those kids kill themselves because they’re being bullied and harassed, the Fundamentalists say “see? Look how bad it is to be gay!”

Similarly, the anti-GMO activists create a culture of hostility and fear around food technology, that creates an environment where it’s almost impossible to produce new GM strains and get them approved. Then they point and say “see? There are only a handful of GM crop strains out there! GMO technology leads to monoculture!” And, like the environmentalists whose effort led to the proliferation of dirty coal-burning power plants, they create an outcome exactly at odds with their professed goals.

The next part of this series will deal with another big area of fear around GMO foods: food safety. Stay tuned!

Note: This blog post is part of a series.

Part 0 is here.

Part 0.5 is here.

Part 1 is here.

Part 2 is here.

Part 3 is here.

In less than three weeks, the end of the world will happen.

In less than three weeks, the end of the world will happen.

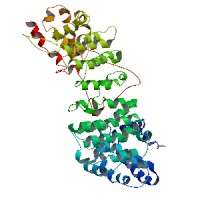

Most of us, I suspect, aren’t really equipped to deal with the notion that everything we believe is important will probably turn out not to be. If we were to find ourselves transported a thousand, two thousand, ten thousand years from now, assuming human beings still exist, they will no doubt be very alien to us–as alien as Chicago would be to an ancient Sumerian.

Most of us, I suspect, aren’t really equipped to deal with the notion that everything we believe is important will probably turn out not to be. If we were to find ourselves transported a thousand, two thousand, ten thousand years from now, assuming human beings still exist, they will no doubt be very alien to us–as alien as Chicago would be to an ancient Sumerian.

Consider this protein. It’s a model of a protein called AVPR-1a, which is used in brain cells as a receptor for the neurotransmitter called vasopressin.

Consider this protein. It’s a model of a protein called AVPR-1a, which is used in brain cells as a receptor for the neurotransmitter called vasopressin. This is Malala Yousafzai. As most folks are by now aware, she is a 14-year-old Pakistani girl who was shot in the head by the Taliban for the crime of saying that girls should get an education. Her shooting prompted an enormous backlash worldwide, including–in no small measure of irony–among American politicians who belong to the same political party as legislators who say that

This is Malala Yousafzai. As most folks are by now aware, she is a 14-year-old Pakistani girl who was shot in the head by the Taliban for the crime of saying that girls should get an education. Her shooting prompted an enormous backlash worldwide, including–in no small measure of irony–among American politicians who belong to the same political party as legislators who say that

Writers like Sam Harris and Michael Shermer talk about how people in a pluralistic society can not really accept and live by the tenets of, say, the Bible, no matter how Bible-believing they consider themselves to be. The Bible advocates slavery, and executing women for not being virgins on their wedding night, and destroying any town where prophets call upon the citizens to turn away from God; these are behaviors which you simply can’t do in an industrialized, pluralistic society. So the members of modern, industrialized societies–even the ones who call themselves “fundamentalists” and who say things like “the Bible is the literal word of God”–don’t really act as though they believe these things are true. They don’t execute their wives or sell their daughters into slavery. The memes are not as effective at modifying the hosts as they used to be; they have become less virulent.

Writers like Sam Harris and Michael Shermer talk about how people in a pluralistic society can not really accept and live by the tenets of, say, the Bible, no matter how Bible-believing they consider themselves to be. The Bible advocates slavery, and executing women for not being virgins on their wedding night, and destroying any town where prophets call upon the citizens to turn away from God; these are behaviors which you simply can’t do in an industrialized, pluralistic society. So the members of modern, industrialized societies–even the ones who call themselves “fundamentalists” and who say things like “the Bible is the literal word of God”–don’t really act as though they believe these things are true. They don’t execute their wives or sell their daughters into slavery. The memes are not as effective at modifying the hosts as they used to be; they have become less virulent. Apparently, a prominent blogger named Rebecca Watson was harassed at TAM last year. And the fallout from her complaint about it, which I somehow managed to miss almost entirely, are still going on.

Apparently, a prominent blogger named Rebecca Watson was harassed at TAM last year. And the fallout from her complaint about it, which I somehow managed to miss almost entirely, are still going on.