After an afternoon of wandering amongst statues of mostly-naked men spurting great gouts of spray everywhere, we left Peterhof by hydrofoil to visit yet another palace, this one belonging to Catherine the Great.

Well, kind of, anyway. Story was, if I got it from our tour guide of the polysyllabic name correctly, that Peter the Great’s daughter Anna decided, when he died and she took over as monomaniacal despot of unlimited power, that his palace was a total dump. She resolved not to have to live in such a trash heap of a place, and commissioned one of her own, this time with knobs that went to eleven. Or twelve.

So she got an architect, explained how she wanted something a lot less cramped and frumpy than Peter’s old digs, and set him loose. She was so pleased with the result that she made him Court Architect and promoted him to four-star general or something. (Quite how a person’s skill at making over-the-top buildings that’d cause the Pope to blush qualifies said person to be a military commander is a detail that escapes your humble scribe.)

So apparently a year later, Anna dies, Catherine takes over the country in a royal coup, and the poor luckless bastard who’d just been promoted into the ranks of the aristocracy ends up getting banished or executed or something, simply by virtue of being a dude that Anna liked. That’s the way it works with royalty–what one hand giveth, the other hand taketh away, and then shoots you in the head or some damn thing.

The palace is now the Hermitage, one of the world’s largest museums. It looks like this. (I didn’t take this picture, I snarfed it from their Web site. I couldn’t get far enough away to get a decent shot.)

Yeah, it’s like that. Catherine, a few thousand of her closest friends, and a few more thousand people who weren’t actually friends with any of them but were reasonably good cooks or seamstresses or something and also had the misfortune to be born into the servant class, which is something they should’ve thought about when they were choosing parents, actually lived here.

The entrance features the same half-dressed, buff sea-god motif that Peter was so fond of.

I imagine the conversation between these two goes something like this:

Buff half-dressed god #1: “Look, as I pet my lion while holding my long, hard rod in my hand!”

Buff half-dressed god #2: “Look, as I pet my strange, jagged-toothed fish-thing from the sunken city of R’lyeh, while I hold my long, hard trident in my hand!”

Buff half-dressed god #1: “Good day to you, sir, and to your weird fish-thing from the depths of mortal’s nightmares!”

Buff half-dressed god #2: “Good day to you, too, and to your lion, and to your rod as well!”

Buff half-dressed god #1: “Let us go down, impregnate some women, and toy with some mortals for sport!”

Buff half-dressed god #2: “Capital idea, old chap. Let us do just that!”

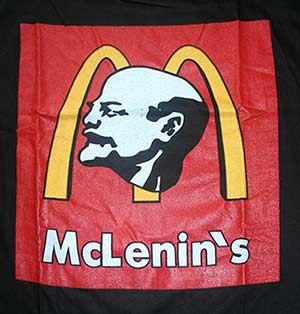

While we were crossing the street toward the entrance, a Russian street vendor selling T-shirts out of the back of his car approached me and offered me a shirt for ten American dollars. When I saw the shirt, I had to get one.

I got it mostly because I sell a “KGB” T-shirt from my online T-shirt shop, so the irony of buying a “McLenin” T-shirt from a street vendor in the former Soviet Union was too good to pass up.

And the more I thought about it, the more perfect it was. A Russian street vendor selling souvenirs to tourists in American dollars, featuring a blatant trademark infringement that’s also a commentary on the fall of the Soviet Union? It’s also, as my sister pointed out, the thinnest T-shirt I’ve ever seen, so all that and shoddy quality too. Now that there is really everything you need to know about the fucked-up geopolitics of the post-Soviet world, it is.

Our transaction complete, the diminutive Russian guide of the brain-shattering name ushered us inside. Once in the foyer, the very first thing we saw was a cat curled up on one of the benches flanking the door.

It was quite a placid cat, utterly unconcerned with the throngs of people all around it.

Our tour guide explained that the Hermitage keeps about five or six cats on the premises as a defense against rodents, since one of the biggest challenges faced by museum curators is rodents and insects that have developed a taste for fine artwork.

I had to pet the cat (over, it must be said, the objections of my father, who quite dislikes cats) before we could venture any farther into the Hermitage’s hallowed halls.

There is a story that when the Bolsheviks overthrew the Russian Tsars, their first impulse was to burn all the palaces to the ground, but they opted to keep them as museums instead–with a propagandistic eye toward inflaming the working classes with fury at the tsars’ decadent lifestyles. The Bolsheviks themselves did plenty to inflame the working classes with fury at them, so I’m not quite sure how that worked out.

Being a monomaniacal Russian despot is a little bit like being Texas. Everything is bigger, and you execute a lot of people. For example, take the stairway leading up from the foyer in the Hermitage. You know how people always put little knobs or carved balls or something on the ends of the banisters, so that actors in Chevy Chase movies can at some point slide down the banister and catch their testicles on them? Yeah, crank those babies up to 12 and you end up with something like this:

It’s probably a good thing Peter the Great was dead by the time Catherine rolled into power, else his punishment flask might’ve looked like that. I’m not really sure what one would do with that thing, short of execution by vodka; the bigness of its size diminishes its utility as a thing to put stuff in considerably. But it certainly is…big.

The Hermitage itself is big. Really, really big. Our guide claims, with a good degree of credibility, that if one were to tour its entire exhibit space and spend one minute looking at each item in their collection, one would be there for about seven years and change. We were there on the one-hour plan, which meant either traveling through the museum at an average speed of Mach 2.4, or seeing only about one-onehundedth of one percent of their collection. Lacking adequate heat shielding and dorsal stabilization for the former, we opted for the latter.

The hallways throughout the Hermitage look something like this.

Every square inch of every surface is covered in paintings and frescoes and reliefs and tilework. The yellow stuff is mostly gold. The overall effect is jaw-dropping, in a sort of over-the-top, confused mishmash of priceless artwork that looks like it was just kind of haphazardly thrown into the air like Ping-Pong balls shot at high velocity from a liquid-nitrogen-powered cannon. (Which I saw a few nights ago, in fact, and it took down part of the ceiling of the building we were in, and the cops got involved, and…but I digress.)

It all looks like this. The whole. Fucking. Place.

My sister, after we’d been walking around with our jaws scraping on the ground for a bit, made a snarky comment along the lines of “Isn’t it amazing what you can do by climbing over the backs of the underclass?” Now, my sister, as I may have mentioned before, is a lawyer, specifically a lawyer who works in the field of contract law. And she said this without apparent irony, as she took advantage of some of her ample leisure time as a privileged First World Westerner to visit a less-privileged country while on vacation from the job at which she earns probably three or four times the median US income and, I don’t know, like eighty-seven million times the average Third World salary or something.

But, honestly, she’s right. I was thinking something similar right before she said it.

And yet…and yet…

I understand the urge to be surrounded by beauty. I get that the Russian leaders were incredibly privileged monomaniacal despots who owed their incredible standard of living to the tyranny and atrocity with which they ruled, I really, really do. I also get that it doesn’t have to be that way. Just a single dollar collected over a single year from each person in the US–an amount of money well within the means of anybody, including the homeless–would probably be sufficient to endow a place of beauty on the scale of the Hermitage, and I think creating beauty is something that has value.

Architect Frank Lloyd Wright wrote that art for art’s sake is a philosophy of the well-fed. I get where he was coming from, but I’m not as cynical. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs would seem to suggest that art is a fleeting and ephemeral thing, attainable (or even relevant) only where our more base needs are being met, but honestly, Maslow can blow me. Were that true, how then did Der Kaiser von Atlantis, an opera written by a Jewish composer being held at the Nazi Terezin concentration camp, come to be? The idea that art is only meaningful to people who are otherwise well-fed and content is something I find not only false, but repugnant. Art, done properly, illuminates every part of the human condition, even–perhaps especially–the bits that are most unpleasant and sordid.

So, yes, I get that the over-the-top exuberance of the palace that is now the Hermitage was built on a foundation of human suffering. I also get that it, more than any of the military misadventure or matters of state that occupied the Russian treasury during the reign of Catherine, is a lasting testament to the human spirit. Had this particular palace never been built, I daresay the suffering of the Russian serf would have been not one whit lessened. As long as we are stuck with the idea of monomaniacal tyrants willing to commit atrocity–and, Russia’s history being what it is, I suspect that was inevitable–there are far worse things they could have done, and did do, than be a patron of the arts.

Though that won’t, I daresay, prevent me from getting snarky about some of that art in my next installment.

My parents went to St. Petersburg & The Hermitage a few years back, and they brought back the very same McLenin’s t-shirts for my son and brother. 😉 Very funny, though they fell apart pretty quickly after a year or two.

Now THAT is amusing. I wonder how long those street vendors have been selling them.

My parents went to St. Petersburg & The Hermitage a few years back, and they brought back the very same McLenin’s t-shirts for my son and brother. 😉 Very funny, though they fell apart pretty quickly after a year or two.

Thank you. You said it beautifully!

Say, are you, by any chance, going to visit Rome on your trip? Because I remember I had the same angry feeling that your sister describes, when I was visiting the St. Peter’s Basilica. And I wonder if it has something to do with the quality of the art. Hermitage touched you — you felt its beauty, despite it being over-the-top. Somehow, St. Peter’s Basilica was nothing but repulsive for me. I wonder what would you think of it, and the art within.

I was just going to mention St. Peter’s and the Vatican Museum, and the conflicting emotions I experienced there.

Both are over the top as far as the decoration and art collections, and I felt humbled, awestruck and forever changed in the presence of such mastery as Michelangelo, Titan, Rubens, Bernini, etc.

But there’s also the anger at the history of the Catholic Church and how all that wealth was acquired, and a vague feeling of guilt at being a willing participant in its continued oppression and hypocrisy.

In the end though, I’m glad I went and had the experience.

Thanks Franklin!

Sadly, no. No visit to Rome. I’ve always kind of wanted to see the Vatican, but I also have decidedly mixed feelings about it. Bloodthirsty as the Russian tsars may have been, I don’t think they can really hold a candle to the Catholic Church; even today, it can be argued that the church’s stance aon contraception alone is responsible for far more human misery and death in AIDS-ravaged Africa than all of the activities of the Russian aristocracy combined.

I feel like if I were to visit the Vatican, I wouldn’t be able to let go of that knowledge for long enough to appreciate what’s there.

Thank you. You said it beautifully!

Say, are you, by any chance, going to visit Rome on your trip? Because I remember I had the same angry feeling that your sister describes, when I was visiting the St. Peter’s Basilica. And I wonder if it has something to do with the quality of the art. Hermitage touched you — you felt its beauty, despite it being over-the-top. Somehow, St. Peter’s Basilica was nothing but repulsive for me. I wonder what would you think of it, and the art within.

Is there something about that that just doesn’t come through well in still pictures? There were a lot of bits from your Peter the Great palace pictures that looked nice, but all I see here is tacky.

Well, to be fair, I’m mostly concentrating on the tacky bits here, the better to snark at them. Still, tacky is a subjective thing; I can understand the impulse toward wanting to be surrounded by beauty, even if the expression of that impulse falls short of the mark.

Is there something about that that just doesn’t come through well in still pictures? There were a lot of bits from your Peter the Great palace pictures that looked nice, but all I see here is tacky.

I was just going to mention St. Peter’s and the Vatican Museum, and the conflicting emotions I experienced there.

Both are over the top as far as the decoration and art collections, and I felt humbled, awestruck and forever changed in the presence of such mastery as Michelangelo, Titan, Rubens, Bernini, etc.

But there’s also the anger at the history of the Catholic Church and how all that wealth was acquired, and a vague feeling of guilt at being a willing participant in its continued oppression and hypocrisy.

In the end though, I’m glad I went and had the experience.

Thanks Franklin!

Peter the Great; Catherine the Great… John the not-so-great-but-perfectly-adequate-in-his-own-way ?

Peter the Great; Catherine the Great… John the not-so-great-but-perfectly-adequate-in-his-own-way ?

WE FOUND xkcd IN RUSSIAN

(and are finding it oddly hilarious)

http://xkcd.ru/735/

MOZGEEEEEEEE

http://xkcd.ru/734/

Wow. Just…wow. It’s a pity I can’ speak Russian!

Gosh – do they?! How do you know? And – do you know why? *boggle*

Sadly, yep, they do.

I suspect its a result of some of the computer security posts I’ve written about, like the ones here and here.

I know they read it because when I find virus dropper and malware sites, often they will contain phrases and sentences lifted verbatim from my LiveJournal posts in them (or in redirectors to traffic handling sites that send visitors on to the malware sites).

WE FOUND xkcd IN RUSSIAN

(and are finding it oddly hilarious)

http://xkcd.ru/735/

MOZGEEEEEEEE

http://xkcd.ru/734/

You are right about art coming from suffering as well as joy. I’m the sort of nerd who reads cognitive theory on my free time. Of course, those books have brought up the tremendous outpourings of art from suffering persons who have never before had the urge to create in their life. It’s part of how the human brain wraps its head around the horrible things which happen to us, and heal from them.

Russia’s artistic history is, in my mind, a bit more interesting for the different economic conditions. I think it was in the middle ages when you started to see Russian villages where nobody farmed, but everyone worked on arts related tasks. It was quite the departure from the rest of Europe. However, I doubt that the peasants who lived their life in creative pursuits felt much less repressed than those in the next village, who farmed. A few centuries later, many estates had a number of performing artists as well as visual artists and artisans, the artistes seem to have been frequently sold when their lord needed cash. Indeed, the collection of primary source Russian documents which I have contains serf ads- and not a one of them is for a field laborer, only skilled workers. There’s also all sorts of accounts of women who’d been forced into the performing arts being taken as unwilling mistresses by their lord.

As an aside, have any of the tours you’ve been on brought up the seeming fixation which Russian nobles seemed to have with human statuary? Real human, not marble.

The appointment to general actually makes a lot more sense, in the context of the imperial Russian service system for nobles. All benefits came from benevolent father-Czar, who was careful to keep the nobles jockeying for his favor. It was much like Versailles that way. Unlike Versailles, though, the nobles were expected to be actually useful. Nobles were expected to do a few decades of service to their country. While the state could assign a noble anywhere, military service was seen as more dignified. It involved foreign travel, courage, bravery, etc. Clerking was boring, drab, and unexciting. Clerks were seen as horrid little paper-pushers who ordered brave men to die on the front lines without understanding it. Worse, many clerks came from peasant stock. The requirement of literacy meant that often, the ranks had to be filled with competent peasants- though this didn’t exactly help with the issue of noble soldiers resenting clerks. As a result of the system, though, a large body of nobles had a military background, and when transferred to other branches of service or civilian life took it with them. The military pervaded everything. Offices were expected, in many cases, to take upon the behavioural trappings of the military. That architect likely had been in the military before, and was serving his country still as the monarch’s architect. With the way that the military pervaded everything, it would have made perfect sense to give him a high military title as a reward. It’s just what civilized people did.

Now that’s interesting. I think in this post alone you’ve probably increased my understanding of Russian social history more than the entire semesters’ worth of Russian history class I had in school.

I’ve been making an effort to learn more about it. I realized that I’d grown up in a town that was 1/3 Russian speaking, and new nothing of the history. Then again, I doubt that the Russian families which I grew up with new much, either.

Recently, I managed to go to the estate sale of someone who’d obviously been a Russian history major, and picked up a large part of their library on the cheap, so I’ve been working through that.

Russia is a very, very different place from the rest of Europe, and in some ways very creepy. For example, even the peasants knew that father-Czar was benevolent. No wrongs could be his fault- there must be some official below him who’s caused things to be the way that they were. There’s all sorts of accounts of peasants who are sure that if they could just tell their tale of woe to the Czar, he’d set everything right. Nobles with grievances felt much the same way. That pervading feel among the peasantry might be partially responsible for them not having had a revolution sooner.

You are right about art coming from suffering as well as joy. I’m the sort of nerd who reads cognitive theory on my free time. Of course, those books have brought up the tremendous outpourings of art from suffering persons who have never before had the urge to create in their life. It’s part of how the human brain wraps its head around the horrible things which happen to us, and heal from them.

Russia’s artistic history is, in my mind, a bit more interesting for the different economic conditions. I think it was in the middle ages when you started to see Russian villages where nobody farmed, but everyone worked on arts related tasks. It was quite the departure from the rest of Europe. However, I doubt that the peasants who lived their life in creative pursuits felt much less repressed than those in the next village, who farmed. A few centuries later, many estates had a number of performing artists as well as visual artists and artisans, the artistes seem to have been frequently sold when their lord needed cash. Indeed, the collection of primary source Russian documents which I have contains serf ads- and not a one of them is for a field laborer, only skilled workers. There’s also all sorts of accounts of women who’d been forced into the performing arts being taken as unwilling mistresses by their lord.

As an aside, have any of the tours you’ve been on brought up the seeming fixation which Russian nobles seemed to have with human statuary? Real human, not marble.

The appointment to general actually makes a lot more sense, in the context of the imperial Russian service system for nobles. All benefits came from benevolent father-Czar, who was careful to keep the nobles jockeying for his favor. It was much like Versailles that way. Unlike Versailles, though, the nobles were expected to be actually useful. Nobles were expected to do a few decades of service to their country. While the state could assign a noble anywhere, military service was seen as more dignified. It involved foreign travel, courage, bravery, etc. Clerking was boring, drab, and unexciting. Clerks were seen as horrid little paper-pushers who ordered brave men to die on the front lines without understanding it. Worse, many clerks came from peasant stock. The requirement of literacy meant that often, the ranks had to be filled with competent peasants- though this didn’t exactly help with the issue of noble soldiers resenting clerks. As a result of the system, though, a large body of nobles had a military background, and when transferred to other branches of service or civilian life took it with them. The military pervaded everything. Offices were expected, in many cases, to take upon the behavioural trappings of the military. That architect likely had been in the military before, and was serving his country still as the monarch’s architect. With the way that the military pervaded everything, it would have made perfect sense to give him a high military title as a reward. It’s just what civilized people did.

Now THAT is amusing. I wonder how long those street vendors have been selling them.

Sadly, no. No visit to Rome. I’ve always kind of wanted to see the Vatican, but I also have decidedly mixed feelings about it. Bloodthirsty as the Russian tsars may have been, I don’t think they can really hold a candle to the Catholic Church; even today, it can be argued that the church’s stance aon contraception alone is responsible for far more human misery and death in AIDS-ravaged Africa than all of the activities of the Russian aristocracy combined.

I feel like if I were to visit the Vatican, I wouldn’t be able to let go of that knowledge for long enough to appreciate what’s there.

Well, to be fair, I’m mostly concentrating on the tacky bits here, the better to snark at them. Still, tacky is a subjective thing; I can understand the impulse toward wanting to be surrounded by beauty, even if the expression of that impulse falls short of the mark.

Wow. Just…wow. It’s a pity I can’ speak Russian!

Now that’s interesting. I think in this post alone you’ve probably increased my understanding of Russian social history more than the entire semesters’ worth of Russian history class I had in school.

I’ve been making an effort to learn more about it. I realized that I’d grown up in a town that was 1/3 Russian speaking, and new nothing of the history. Then again, I doubt that the Russian families which I grew up with new much, either.

Recently, I managed to go to the estate sale of someone who’d obviously been a Russian history major, and picked up a large part of their library on the cheap, so I’ve been working through that.

Russia is a very, very different place from the rest of Europe, and in some ways very creepy. For example, even the peasants knew that father-Czar was benevolent. No wrongs could be his fault- there must be some official below him who’s caused things to be the way that they were. There’s all sorts of accounts of peasants who are sure that if they could just tell their tale of woe to the Czar, he’d set everything right. Nobles with grievances felt much the same way. That pervading feel among the peasantry might be partially responsible for them not having had a revolution sooner.

Gosh – do they?! How do you know? And – do you know why? *boggle*

Sadly, yep, they do.

I suspect its a result of some of the computer security posts I’ve written about, like the ones here and here.

I know they read it because when I find virus dropper and malware sites, often they will contain phrases and sentences lifted verbatim from my LiveJournal posts in them (or in redirectors to traffic handling sites that send visitors on to the malware sites).

Hermitage is the museum located in the actual Winter Palace. In Russia, Peterhof is never called this name. And Anna, who started the construction, was Peter’s niece. She was succeeded by Peter’s younger daughter, Elizabeth, who nearly finished the Palace. However, she passed away just before it was finished, and her successor, Peter the Third (Elizabeth’s nephew and Catherine the Great’s husband) signed off on the construction. It was completely finished after the coup that his wife orchestrated in 1762; he was killed in the procedure.

Hermitage is the museum located in the actual Winter Palace. In Russia, Peterhof is never called this name. And Anna, who started the construction, was Peter’s niece. She was succeeded by Peter’s younger daughter, Elizabeth, who nearly finished the Palace. However, she passed away just before it was finished, and her successor, Peter the Third (Elizabeth’s nephew and Catherine the Great’s husband) signed off on the construction. It was completely finished after the coup that his wife orchestrated in 1762; he was killed in the procedure.