The Hermitage houses a very large collection of Renaissance-era and Impressionist paintings, mostly located in long halls above the throne rooms that occupy much of the ground floor of the main building in the palace complex.

At some point, were I to live forever, I would dearly love to take the seven-year tour of the Hermitage. Even then, I suspect I wouldn’t be able to fully appreciate everything it has to offer, but I bet there are quite a few real treasures hidden in amongst the tacky bits and the bits that have gold all over them–but I repeat myself.

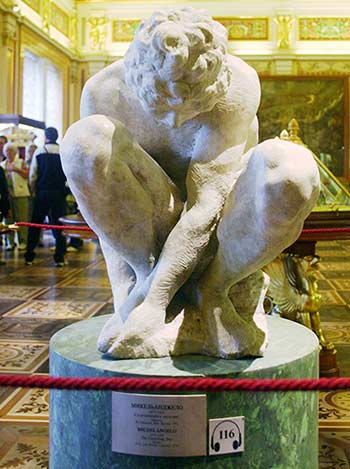

The main floor also houses the only Michelangelo in the Hermitage’s collection, this unfinished statue that had been commissioned by some church dude or other and then left half-completed when said church dude changed his mind and decided he wanted something else entirely. (I’ve had clients do that to me, and it’s enough to provoke a murderous rage even when I haven’t invested hundreds of man-hours into chipping away at gigantic blocks of stone with tiny hand tools.)

After being bitten and infected with the stone virus, he waits. Quietly, day after day, year after year, he waits. When the stars are right, and the hold of the virus weakens, he will drag himself free of his marble prison. Then he will shamble across the great halls of the museum at night, needing only the blood of the living to remove the curse and fuel his unholy desire for vengeance. On that day, they will pay, the ones who kept him caged here behind ropes of red velvet, a curiosity to attract the throngs of tourists. Oh, yes. They will pay.

This next sculpture has an interesting tale behind it, which lives on as a warning to artists of all stripes.

It was intended to illustrate a popular story about a dolphin who befrended a boy. Every day, so the story goes, the dolphin and the boy would play together in the water, venturing farther and farther away from shore as they frolicked in the salt spray beneath the warm sun.

Inevitably, of course, the dolphin’s knowledge of human physiology failed him, and he misjudged the length of time the boy could hold his breath, with the predictable result that the boy drowned. The dolphin was so devastated by this that he bore the boy away on his back until he, too, died, of loneliness or grief or syphilis or something.

Now, the first thing the astute visitor might notice upon seeing this sculpture is that there is no dolphin in it. The thing carrying the boy here looks like nothing so much as Daffy Duck suffering from ‘roid rage, with his body replaced by that of some horrifying half-fish abomination from the depths of the sunken city of R’lyeh.

This is because, apparently, the artist who carved this sculpture had never heard of a “dolphin” before, and knew nothing about them save for the fact that they were big and lived in the ocean, and they fed on the souls of mortal men whenever the planets aligned themselves properly in the night sky.

I seriously don’t know how the human race accomplished anything before Google and Wikipedia. Where did people go if they needed to know what a dolphin looked like, or who that really hot guest star was in that one episode of Star Trek: Voyager when they thought they had found their way back to the Alpha Quadrant, and then at the last minute it turned out they didn’t?

Strange Daffy Duck/fish-thing hybrid properly admired, we headed upstairs to the galleries above. Even the stairways in the place are richly decorated. No, scratch that. Even the minor secondary stairways are decorated with the most ostentatious, gaudy, over-the-top kind of junk you can possibly imagine. Like this statue in the stairway up to the second-floor exhibit halls, for example.

At least I hope that’s a statue. Don’t blink! They are fast, faster than you could believe. And they can throw a mean laurel wreath.

I found an open window on the top floor that looked out into the courtyard of the palace complex and some of the buildings behind. And I thought Portland was gray and rainy…

That huge, sprawling, elongated building I posted a picture of earlier? Yeah, that was only one building in the complex. Catherine actually lived here.

Our tour guide whose Name Can Not Be Uttered abandoned us to wander the artwork in the halls, partly so she could take a phone call. From a lover, I suspect, judging from her body language and the huge grin on her face when her phone rang. I don’t speak a word of Russian, but just her expressions alone suggest to me that she may have been having phone sex with whoever was on the other side. But I digress.

One of the first bits of artwork in the upper halls is this Rembrandt, showing an angel stopping Abraham from sacrificing his son Isaac. He actually painted two versions of this piece (and several sketches and at least one etching), one of which hangs at the Hermitage.

This story has always disturbed me, even back in the days when I was actually Christian. Seriously, what kind of god tests a person’s faith by telling that person to murder his son? Surely an omniscient god already knows what the outcome will be, so the test itself seems like an exercise in petty cruelty.

But more to the point, what kind of person hears voices saying “sacrifice your son” and actually does it? Nowadays, we lock people like that up, and rightly so. Leaving aside for a moment how profoundly fucked up it is to murder your children because the voices in your head tell you to, and even going with the notion that the voice telling you to do this profoundly fucked-up thing is in fact the voice of god or some god-like supernatural entity, the cold and inescapable fact is that any god that tells you to murder your kids is not a god worth worshipping. Not at any price.

Even if he says “Haha! Just kidding!” when you actually go to do the deed.

A lot of artists of the time painted with religious themes. In some ways, artists have it easier than writers. Language is a living, breathing thing, and changes all the time; William Shakespeare is one of the very few people who I can truly say really is as brilliant as everyone says he is, in spite of the number of folks who tell you that he really is brilliant.

A lot of artists of the time painted with religious themes. In some ways, artists have it easier than writers. Language is a living, breathing thing, and changes all the time; William Shakespeare is one of the very few people who I can truly say really is as brilliant as everyone says he is, in spite of the number of folks who tell you that he really is brilliant.

But Shakespeare gets a bit of a bad rap in part because the language makes him less accessible to modern readers. He really was the Quentin Tarantino of his day–witty, vulgar, more than a little bit crass, given to bad puns, and obsessed with Uma Thurman–but he seems very stuffy and highbrow to modern high-school students because time has weathered his words and made his particular brand of humor less visible.

Artists don’t have to deal with that. They paint a picture and it’s done. No matter what language the audience speaks, a picture is a picture.

At least to a certain extent. The visual language of art changes, true. But more importantly, the social context changes. Artists tell a story, and that story assumes a cultural framework understood by both the painter and the audience.

With religious themes, it’s a gimme. Someone can paint a picture of Moses coming down off the mountain and two thousand years later people will still understand the reference, because religious memes tend to stick like glue. But sometimes, even the cultural references change, and that’s a dangerous thing. When the cultural framework changes, and the audience becomes disconnected from the artist, the audience may tend to invent their own story.

And when that happens, things can get weird.

The story I put to this picture probably isn’t what the artist intended at all. I’m sure this refers to some kind of myth or fable or something that all the people he was painting for immediately understood, but me? I got nothin’. The story I put on this painting goes something like this:

Dude with wings: Look! I have wings. Let me fondle your breast.

Blonde chick in the dress: My, you do have wings! And what long and…feathery wings they are. I hear that big wings means a big…why yes, of course you may fondle my breast!

Cherub-looking thing: Ooh, look! Someone left a bow just lying around down here.

Effeminate-looking dude in the robe: Look at my fine wares! They are fine and…um, wares. I, too, wish to fondle your breast.

Cherub-looking thing: Dude, seriously, free bow! Just lying on the ground! It’s a bit too big for me, but still.

Blonde chick in the dress: Do you have a big…toga?

Effeminate-looking dude in the robe: Alas, my toga is of undistinguished size. Dare I say, pedestrian, even.

Cherub-looking thing: Of course, this bow has no bowstring…

Blonde chick in the dress: Then you may not fondle my breast. Girl’s gotta have her standards.

Dude with wings: Sorry, dude. Playaz play, losers lose.

Blonde chick in the dress: Come, fly me to the top of that building back there and I will give myself to you in ways that will make Abraham kick a hole in a cinder-block wall.

Cherub-looking thing: Forget the breasts for a minute. Free bow down here. Right down here!

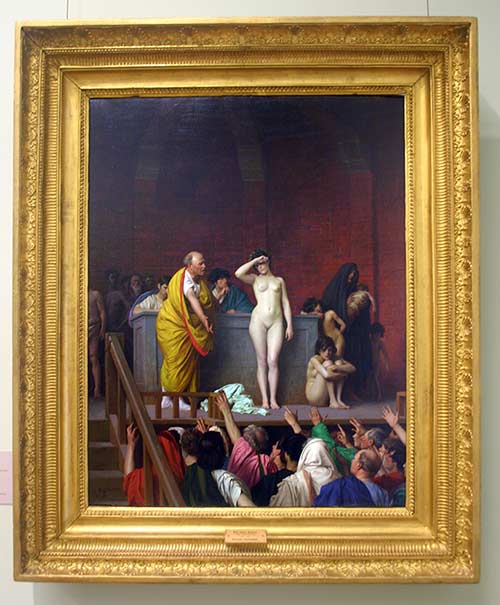

This next painting…well, I’ve had weekends that look like this.

Of course, the weekends I’ve had like this, the people up for auction were there ’cause they wanted to be. Take out that element and it gets pretty messed up, you know what I mean?

And speaking of messed up, the Hermitage is home to a Rembrandt which, try as I might, I could not get a good picture of to save my life. This pic is taken from Wikipedia:

Back in 1985, a guy came into the Hermitage and threw acid all over this painting, doing so much damage that it took restorers eleven years to fix it. When asked why he’d done it, he explained that public depictions of nudity were obscene and pornographic, and he wanted to help purify the world or make it safe for children or some such thing.

Which is pretty messed up, in my book. I’m not quite sure how we go about making people so ashamed of their own bodies that they feel that level of disgust at the human form. That mindset utterly baffles me, to the point where I feel unable to connect even intellectually with it.

That’s not the only interesting thing about this painting, though. The other interesting thing about this painting is that Rembrandt used his wife as the model for the woman you see here, but put his mistress’s head on her.

Dude had it goin’ on, yo!