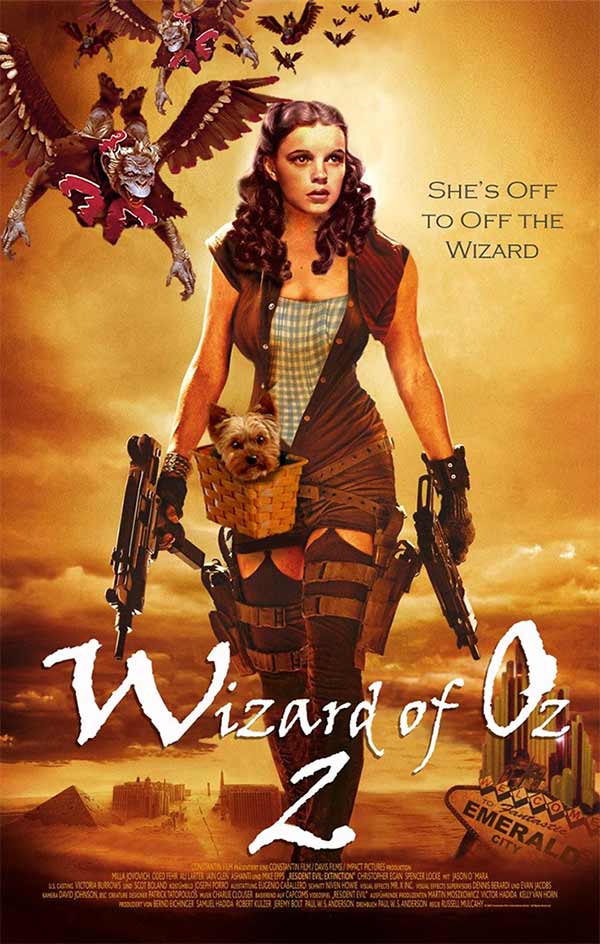

Noted Without Comment: Wizard of Oz 2

26

I’ve mentioned this before, but one of the things that baffles me the most when I say I want to live forever is the folks who say “Wouldn’t you get bored?”

The question totally boggles me. Bored? Who on earth has time to be bored? Life changes constantly. In the last two thousand years, we have gone from Bronze Age tribalism through the Iron Age, the rise and fall of the empire of Rome, feudalism, the Renaissance, the discovery of a new continent, industrialization, the rise of mass communication, to atomic power and the beginning of the exploration of the physical universe. In all of that, we have seen incredible changes in society, philosophy, science, art, engineering, customs, tradition, and knowledge. Who would say of a man born in the time of Jesus and still alive today, “But aren’t you bored?”

The question to me seems to show a projection of the present onto the future–I almost wonder if the folks who ask aren’t envisioning people commuting to work, stopping for lunch at McDonald’s, listening to Rush Limbaugh on the radio, heading home through rush-hour traffic to watch reruns of “Friends” on TV in the year 6,000. I think that’s particularly strange given that, in the memory of people who are still alive today, the United States has moved from a largely agrarian nation to a post-industrial nation, pausing along the way to split the atom, tame Niagra Falls, and put men on the frikkin’ MOON.

No, I don’t think I’d be bored.

In fact, I’ve started to make a list of some of the things I would like to live long enough to see–things for which a single “ordinary” human lifespan is insufficient. The next thousand years offers exciting prospects for the human species unmatched in the last ten thousand, and I want to see what happens. For example:

What will happen when we discover evidence of life elsewhere in the universe? Given the incomprehensibly vast scope of the physical universe, it seems profoundly unlikely that we alone live here. If the emergence of life is so unlikely that it happens even once out of ten billion solar systems, that would mean it’s everywhere–the physical universe is just that big. If, as seems more likely, it develops and takes a foothold anywhere that it is not prevented from doing so by the laws of physics, then it’s probably ubiquitous. What does it look like? How does it work? What would it mean to us to learn that we’re not alone? What form would it take? Where will we find it? What implications will it have for philosophy, religion, morality, our conceptions of ourselves? What will we learn from it? Will the knowledge that it exists make us feel more connected or more disconnected from the universe and from each other? Will we see life as being more sacred or less sacred?

Will we succeed in moving beyond our own fragile home on earth? Where will we go? What will we learn? How far will it be possible for us to extend our reach? How will we change in the process? Will knowing that we have left the only home humanity has ever had for its entire existence change our conceptions of ourselves, and in what way? How will we adapt?

What does a post-scarcity society look like? From the stone knives used by our earliest hominid ancestors to the Large Hadron Collider, everything we have ever built has been built in the same way–by taking the materials we find and heating, cooling, chipping, hammering, carving, cutting, and pounding away at them until they’re shaped to do the task we want. This crude method of building things, which has been refined only in degree but not in kind since the days of flint knapping and bearskins, necessarily means resource scarcity, because it is limited both by the natural raw materials available and by the man-hours of labor needed to fashion the raw materials into finished things. But what happens when we gain the ability to put things together on a molecular level exactly as we want to? Oh, then everything changes. Then it becomes possible to make just about anything–food, Ferraris, fuel, iPods, spaceships–from dirt and sunlight. No more scarcity means no more resource competition, no more competition between the “haves” and the “have nots,” no more division of nations into “first world” and “third world.” What will that mean for human society? How will it change the way we interact with each other? Who will be the first to figure out molecular assembly, and how will that affect everyone else? Is it true, as some folks say, that wars are fought for resources first and ideology second, and if so, will a post-scarcity society really make war obsolete? Or will we simply shift from competing for material resources to competing for ideas?

What happens when we gain the ability to control ourselves on a molecular level? Biomedical nanotechnology is a hot field of research, barely out of the starting gate–the state of the art right now is roughly at the state of the computing art during the time of Charles Babbage. We know it is possible to build machines that can change and repair living organisms on a cellular or molecular level–we just don’t know how to get there yet. But what happens when we do? What does a human society look like when you take away the inevitability of deterioration, aging, enfeeblement, and death? And more than that–what does it mean to be able to make modifications to to ourselves on the level of our DNA? When you give people the ability to change in that way, will you see a society of nearly-identical supermodels, or a society of people with orange fur and tails? Will we begin to enforce common standards of physical appearance, or will we start changing ourselves in all sorts of novel and interesting ways? If people can change their physical sex at will, and be completely functional in whatever their chosen physical sex is, what will that mean for gender differences? How will that affect society, when some of our most basic assumptions about what being human means become obsolete?

What happens when we remove the biological limitations on our brains and bodies? Human brains and human bodies do not have infinite capacity. Our brains are limited, both in terms of raw processing power and in terms of the concepts we are easily able to imagine and comprehend. Are there things about the physical universe that we simply do not have the capacity to understand, in the same way that a dog does not have the capacity to understand calculus? Are we nearing the limits of what we are able to understand about the physical world around us? What will it mean if we can re-wire our brains to add capacity? What will it mean if we can change our bodies to give ourselves abilities we lack now–the ability to breathe underwater, say, or to adapt to hostile environments? How much of what we consider our “humanity” is a consequence of our limitations and of the environment we live in? If we begin to diverge from one another in these ways, will we lose our ability to relate to one another, or will this simply serve to underscore the ways in which we are all connected? What will we learn about ourselves? What will we learn about the world we live in?

What happens when we encounter the first non-human intelligence? There are many ways this might come about; it could be an AI, a non-human race, even an animal that’s been modified to have a higher level of cognitive capability. How will seeing an intelligence that isn’t ours affect us? What will we learn about ourselves? Will we discover new ways of comprehending the universe? Will we discover blindness in our own way of thinking, and if so, how will we be better for it?

What kind of macroengineering projects are we capable of? The largest-scale engineering we’ve ever done is really, when you get right down to it, not that far above Stonehenge. But what happens when we become capable of building on a global scale, or larger? The Space Elevator is a good beginner’s macroengineering project, but what comes next? Will we be able to terraform planets? Build ringworlds? What will those things look like? How can they be done? How will they extend our capabilities as human beings? How will transforming the physical universe transform us? Will we encounter anyone else who is already building on this scale? What will that mean for us?

Now, to be perfectly honest, even if these things were not on the horizon, even if things would always be as they are now, I would still want to live forever. There is hardly a day that goes by that I don’t encounter something that is so mind-blowingly beautiful that it makes me grateful to be alive; the world just as it exists in this instant in time is so filled with wonder and beauty that I could live for thousands of years and never grow tired of it. There is so much joy to be had, all around, that I can’t quite fathom living in anything other than a perpetual state of awe.