Seen on the way back from lunch last week. Apologies for the poor quality of the image; it came from my iPhone camera, and my windshield is very dirty.

Seen on the way back from lunch last week. Apologies for the poor quality of the image; it came from my iPhone camera, and my windshield is very dirty.

Last night as I was going to sleep, zaiah started drawing on my back.

There’s something delightfully intimate about this sort of activity. It’s a really neat way to express affection and love, and it’s an inherently creative act, too. I highly recommend it.

She’s also a better artist than I am. Here’s what she drew. (The Kanji mean “Toy,” which has been her name for me since very early in our relationship.)

My sweetie zaiah is in town for the week, and last night I slept curled up beside her with a young kitten sleeping under the covers on my hip.

The kitten is actually zaiah‘s reason for being here. She went to her new home this afternoon; she was bought by a family here in Atlanta. zaiah arrived in town yesterday, kitten in hand, and met the kitten’s new family today.

This, ladies and gentlemen, is Ruby. Ruby is a sixteen-week-old, aqua-eyed bundle of fluffy, fuzzy joy in a convenient carrying package.

This, ladies and gentlemen, is Ruby. Ruby is a sixteen-week-old, aqua-eyed bundle of fluffy, fuzzy joy in a convenient carrying package.

I immediately fell in love with her. She is inquisitive, curious, happy, eager, and above all else, she is absolutely, utterly fearless. Ruby lives in a world where everything from the box on the shelf to the mysteries beyond the closet door are filled with delight and wonder. In her world, every person is her friend, and she takes charming delight in meeting new people. Every other animal wants to play with her, every change in her environment is cause for celebration.

It didn’t take Ruby long to make herself right at home. She bounded out of her carrying cage, checked me out enthusiastically, and rubbed against my hand for a while. Then she bounced around the apartment with unrestrained glee, heedless of Liam following her about like a shadow. She played with David for a while, checked out his Bowflex (surely the world’s biggest and most entertaining kitten amusement park, when it comes right down to it–lots of things to crawl under, lots of dangling things to bat at). Finally, when she reached that kitten stage of “Noo! I’m so tired I can’t keep my eyes open any more, but I want to keep playing!” she bounced back into my bedroom to curl up under the covers with me for bed.

There’s a lesson we could all learn from Ruby, about how our perceptions of the world shape the reality.

Many New Agers like to think that the principles of quantum mechanics prove that the world is created by our perceptions. This isn’t true in a literal sense, at least not the way they think it is; one of the problems of science is that it uses a highly specialized vocabulary, and words like ‘observer’ when used by a physicist don’t mean what they do in the common vernacular.

Nevertheless, our assumptions, expectations, and beliefs do change our experience of the world.

I’ve written before about the phenomenon of confirmation bias–the natural, unconscious tendency of human beings to see and give special weight to anything that confirms our beliefs, and to disregard things that contradict our beliefs. People who believe that psychics can predict the future will remember occasions when a psychic has seemed to make a prediction that comes true, but forget the dozens of predictions that didn’t come true. People who believe that women are poor drivers will remember the woman who cut them off in traffic, but forget the man who did. And so on.

Scientists have to deal with confirmation bias all the time. Medical tests are set up as double-blind tests, so that not even the doctor or the researchers know which is the placebo and which is the real drug, to help prevent confirmation bias. Researchers will intentionally look for evidence that proves their hypothesis wrong, rather than evidence that proves their hypothesis right, in part because confirmation bias makes it far too easy to see evidence that seemingly supports a hypothesis. (This is one of the ways you can spot flim-flam artists and pseudoscience, by the way.)

As strong as confirmation bias is when you’re dealing with intellectual beliefs, though, it’s a thousand times more devastating when you’re dealing with emotional responses.

On another forum I read, the subject has come up about relationship agreements, and specifically about relationship agreements in polyamory.

On another forum I read, the subject has come up about relationship agreements, and specifically about relationship agreements in polyamory.

Often, people who choose to explore any kind of non-monogamous relationship face a great deal of trepidation. We’re told, daily, from the moment we’re born, certain things about relationships, like “if your partner really loves you he will never want anyone else” and “if your partner has sex with some other person, your relationship is doomed.”

Folks who know, intellectually, that these things are not necessarily true may nevertheless feel emotionally threatened by the reality of a partner taking another lover. And, quite commonly, one of the ways they seek to address this is to sit down and negotiate a set of rules to help them feel more secure and help guide them through the perceived hazards of non-monogamy. This is probably the single most common approach I’ve personally seen amongst folks, especially married couples, new to polyamory.

This does have something to do with Ruby the kitten. Hang on, I’m getting to that.

These contracts are sometimes quite detailed. This contract, for example, is a 7-page PDF that specifies, among other things, what pet names an ‘outside’ lover is and is not permitted to use, what words an outside lover is and is not allowed to use to describe a relationship, and what kinds of sex ann outside lover is an is not allowed to have.

It’s nothing, however, compared to another contract I’ve seen, which I seem no longer have a link for, that spells out (in over 40 pages of single-spaced type) all of the above plus the positions an outside lover is permitted to have sex in, the number of miles a member of the primary relationship is allowed to drive to go on a date, what restaurants a member of the primary couple is not permitted to bring any other partner to, and so on.

And I can’t help but marvel, as I read these contracts, at how brilliant they are as testaments to fear and insecurity.

Now, I’m not trying to say that people in a relationship should never make any rules or agreements. As I’ve said in the past, I think there are some rules that are not only valuable but necessary. Rules about joint ownership of property and children, for example. I also think it’s wise for non-monogamous–and monogamous, for that matter–sexual partners to negotiate safer-sex boundaries.

It seems to me, though, that many of the agreements people make about non-monogamy, particuarly when it comes to things like amount of time that people are permitted to spend with other partners and the activities people are permitted or forbidden to engage in with other lovers, reveal a great deal about the assumptions they make.

And none of what they reveal is good.

Rules of the sort you’ll find in the contract I linked to above seem predicated on one very simple assumption: “Polyamory is a threatening and scary thing, and if I don’t keep my lover on a very short leash, my lover is going to stomp all over me and then destroy our relationship.” That assumption is in turn resting on a deeper assumption, like the elephant standing on the world-turtle’s back: “My lover doesn’t really want to be with me. I’m really not all that great. There’s nothing particularly special or desirable about me; my lover would really prefer to be with someone else. If I give my lover free reign to do as he pleases, he’s going to realize that and leave me.”

Now, I used to have a cat named Snow Crash. Snow Crash is in all respects the polar opposite of Ruby. He found changes in his environment to be frightening and upsetting, and would hide under the sink when things changed. He was deeply suspicious of strangers, and tended to run when someone new came over.

Snow Crash and Ruby live in the same world–a world where some change is good and some change is threatening, where some people are kind and some people are not. But their experience of the world is very, very different.

Your experience of the world depends to a great degree on the assumptions you make. The machinery of confirmation bias assures it.

Your experience of the world depends to a great degree on the assumptions you make. The machinery of confirmation bias assures it.

If you believe that your partner really does not value you and does not want to be with you, you’ll find confirmation of your worst fears in everything you see. Do you feel like you aren’t special? Then if your lover calls his other lover by the same name as he calls you, or takes his other lover to your favorite restaurant, you will feel replaceable. Do you feel like your lover doesn’t value your relationship? Then if your lover is ten minutes late coming home from a date, your mind will go to visions of all the fun he’s having without you and the revulsion and disgust he feels at having to return to someone as worthless as you, rather than to the idea that it’s raining outside and the traffic must be a mess.

These assumptions become particularly insidious and particularly toxic when they are incorporated into your self-image. Do you think “I am a jealous person” rather than “I am a person who sometimes feels jealousy”? Do you think “I am an insecure person” instead of “I am a person who occasionally feels insecure”? Then your jealousy or your insecurity will become mountains made of stone, because changing your sense of self is always difficult.

So naturally, confronted with these immense mountains of stone, you will be tempted to go around rather than through. Nobody likes to feel unloved or valueless in the eyes of a partner. If oyu start from the assumption that these things are true, and you make that assumption a part of your self-identity, then you can become quite helpless in the grip of these feelings, and it can start to feel reasonable to keep your partner on a short leash, if only to make yourself feel better.

But here’s the thing, and it’s a point I’ve touched on before:

If your assumptions are true, and your partner really would rather be with someone else, then rules will not save your relationship. If your assumptions are false, and your partner does value and cherish you, then rules are unnecessary.

Think about what it means to start with a different set of assumptions. Think about what it means to start with this: “My partner loves and cherishes me. My partner is with me because he wants to be with me, and because I add value to his life–value that nobody else can ever add. If I have a problem, then my partner will want to work with me to solve it, because my partner cherishes me and wants to honor our relationship. I am a person, unique in all the world, who my partner chooses because he sees that value in who I am.”

When you start from that assumption, your perception of the world changes. You will tend to see things which confirm your assumptions, good or bad; start with positive assumptions and you will see the truth of them, just as if you start from negative assumptions you will see evidence to support them.

The same is true for the assumptions themselves. Start from a place that you are a jealous, insecure person and that’s just the way you are, and it will become your reality. Start from the assumption that you are a person who sometimes feels jealous or insecure, but there are things that you can do and choices you can make to address these insecurities and jealousies, and that will become your reality.

It does not bother me if my lover goes to my favorite restaurant with a date, or if a lover calls someone else by a pet name that she uses on me. I do not write contracts forbidding these things because they can not challenge my sense of self. I know that my lovers value and cherish me, and make choices that honor our relationship, because they want to be with me.

It is a simple thing, to start with a different set of assumptions. Not always easy, perhaps, because assumptions become well-worn grooves in your brain, and creating a new track takes work. There is comfort in the familiar, including in familiar assumptions.

But who do you think is happier, Ruby or Snow Crash?

While i rarely remember my dreams, every now and then I have one that’s a doozy. A few nights back, I had a dream that I took over the world.

Not in a military sense, though, and not in a James Bond “siezing control of all the natural resources” or “building a flying orbital fortress sense.” It was a lot more…transhumanist than that.

It started out with me on a group of islands somewhere in the middle of nowhere. I had developed gap generators–anyone who plays the game Command & Conquer Red Alert will know what I mean. Towers that blank out the area around my island to air and satellite photography.

I also had a lock on tech that is to current high tech what an M-16 is to a flint knife. We’re talking general nanoscale assemblers, instantaneous global real-time intelligence, near-instant suborbital travel to any point on the globe, force fields, force manipulators, the works.

So I did what anyone would do in that position, if they were me: started issuing edicts. I developed a very simple system for it, in fact. I’d send out a mass-media, all-channels broadcast to some place, telling their government what to do. If they failed to comply, then the folks responsible for the failure would get zapped by lightning, or find their homes and offices crumbling to dust under a flying swarm of microscopic robots, or stuff like that, and then I’d repeat the broadcast. Rinse and repeat until compliance.

A lot of governments took strong objection to this, and tried all sorts of things to get me to stop. They’d send navies after me, which would find themselves blocked by invisible walls hundreds of miles out. They’d launch missiles at me, which I would snatch out of the air and add to my collection. In one particularly vivid and detailed part of the dream, the American government sent a nuclear attack sub after me, reasoning that I wouldn’t see it coming; I snatched it out of the water, and sent the crew back to Washington on a suborbital ballistic transport with a note reading “Here’s your guys back, thanks for the sub!”

I don’t remember all the edicts that I issued, but I do remember that some of them included:

– An immediate end to laws mandating sexual segregation and sexual oppression in the Middle East;

– An immediate laying down of weapons by all armed, militant religious and paramilitary groups, with a 24-hour deadline (after which armed militants found themselves being taken apart, along with their weapons, by swarms of nanobots);

– Immediate closing of prison camps all over the world, including the prison at Guantanamo;

– Patent reform in the UK and the US;

– Immediate, unconditional, and unrestricted civil rights for gays and lesbians everywhere in the world;

and so on.

You know, looking back, I think I’d probably make a pretty good dictator of the world.

One of our neighbors keeps trying to steal cable television.

We know this because our neighbor isn’t terribly good at electronics or even the most basic principles of electrical cabling. Our cable modem service keeps going out; last week, while I was visiting figmentj, it went out for three days (leaving my roommate David, whose car still hasn’t been replaced since it was totaled a couple months back by an unlicensed driver, without transportation or World of Warcraft).

The technical guy sent out by Comcast discovered that the main cable junction box feeding our apartment complex had been pried open, and the miscreant, in his clumsy and ham-handed efforts to steal cable, had made a right proper mess of the cable connections. Our cable connection had been cut entirely, and a much of the rest of the junction box had been screwed up as well.

Last night, just at the start of a boss fight in Heroic Pinnacle (that doesn’t mean much to you if you don’t play World of Warcraft, so substitute “a difficult situation where other players were counting on me”), it went out again. David ran outside to try to catch the miscreant, and discovered that the junction box had been pried open again and cables were strewn all over the place.

That’s not what this post is about. That’s just the back story.

This post is actually about intellectual property and opportunity cost. Now, before I get into a full-on rant here, I want to disclose something up front: I have a horse in this race. This is an issue that matters to me because I am a creator of work that is often taken without my permission, something I’ll get into in a bit. This is not an abstract thing for me; it’s something that affects me personally. If it sounds like I’m taking the issue of intellectual property personally, it’s because I am.

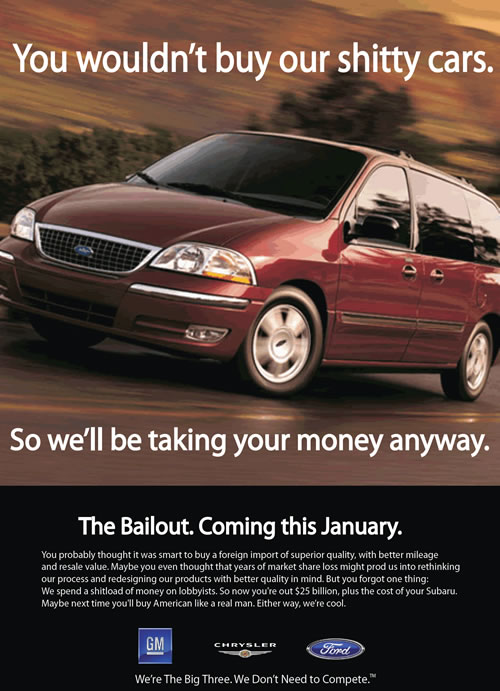

We live in a society that is very hostile to the idea of intellectual property. People tend, by and large, to think very little of stealing content; in fact, entire social systems have grown up around it. We are, by and large, okay with bootleg software, illegally downloaded music, and all manner of disregard for the intellectual property of others, in ways that would horrify us if they were applied to physical property.

This stems, I think, in no small part from the fact that we are as a society hostile to intellectual pursuits in general. It’s pretty tough not to notice that US culture today is steeped in anti-intellectualism; an anti-intellectualism so virulent that many folks won’t vote for a political candidate if he’s perceived to be too intelligent or too well-spoken. It’s not surprising that a society that thinks so little of intellectual endeavor should think so little of the products of that endeavor.

In fact, I’ve even heard people argue that intellectual property as a concept should not exist at all. In a strange throwback to Communist ideals, I’ve heard it argued that if a person dedicates twenty years of his life and his entire fortune to the development of a new idea or the invention of a new gadget, his knowledge and the fruits of his labor should be available freely to all, so that anyone who wants to make knockoffs of his invention or who wants to sell the results of his idea should be free to do so without giving anything back to the person who worked so hard to develop it.

I think that’s fucked up beyond all measure, frankly.

Now, granted, not everyone takes that extreme a view to the notion of ownership of the results of one’s cognitive labors. A much more common argument in favor of intellectual theft is the “zero opportunity cost” argument.

This argument goes something like: “Well, there was no way I was going to buy Photoshop. If I steal a copy of Photoshop, Adobe has not lost anything, because I was never going to buy it to begin with. Because Adobe has not really lost anything, no harm has been done, and it’s OK for me to pirate it.”

Same for copying music, stealing cable, or sneaking into the movie theater; “I wasn’t going to pay for those things anyway, so it’s not like they have lost any sales. They’re not losing anything, so it’s OK for me to do this.”

It’s a bullshit argument, front to back. The opportunity cost is rarely truly zero.

My neighbor is a great example. In his attempt to steal cable, he has damaged property not belonging to him, he has interrupted a service that I’m paying for, and he has made Comcast send out repair technicians twice now. (Tomorrow will be a third time; they’re replacing the entire enclosure around the cable junction box, because in prying it open he damaged it beyond repair, and the junctions inside are now getting rained on.)

It’s a bullshit argument even if the piracy doesn’t involve crowbars to someone else’s property, though. Take Photoshop (or don’t, please!). Most of the folks who pirate it are not professionals; they don’t do print production for a living. That means they don’t use, or even know about, anything even close to 90% of its capability; they have no need of a $700 image editing program, and there’s no question that Adobe is not out $700 for everyone who steals Photoshop.

What these pirates need is a $49 image editing program; and that’s a $49 image editing program they’re not going to buy because they stole Photoshop.

And hell, there’s a free image editing program called The GIMP that they can have for nothing, legally! It’s not Photoshop and it can’t do everything Photoshop can do, but the folks stealing Photoshop don’t need everything Photoshop can do.

But that’s not even the most important reason the argument from opportunity cost is bullshit. The argument from opportunity cost is bullshit because it rests on a sense of entitlement. Bluntly, you don’t have the right to benefit from someone else’s work without paying that person, even if you would rather go without than pay.

People steal intellectual property and people steal services because they want the benefit. They see benefit in owning Photoshop or having cable TV. Having these things makes their lives better in some way. And they feel entitled to that benefit; they feel that they deserve to have their lives made better from the labor of other people.

If I do something that has value, and you want that value, pay me. If you don’t want to pay me, then don’t take the value. You are not entitled to gain value from my work for free.

Even if–and I’m looking at the folks who steal music here–you think that the money I want is excessive or that I am unreasonable.

If you think that I am unreasonable and the value I offer is not worth what I am asking in exchange, that’s fine. Don’t take the deal. But don’t then also believe that you’re entitled to have that value, and you have a right to steal it just because you didn’t take the deal! You may think the RIAA is a bunch of asshats who wouldn’t know ‘reasonable’ if it bit them on the cocaine-powdered nose, and I’d agree with you, but that still doesn’t excuse the fact that you have no right to take value from them for free just because they’re asshats.

It gets simpler to understand when we think about tangible things. If I rent cars, and you sneak into my parking lot, you hot-wire one of my cars, and you take it for a joyride, then you return it to my lot the next morning and I don’t notice what you’ve done, you could argue that the opportunity cost was zero. I didn’t lose anything’ the car is still there, and you weren’t going to rent it from me anyway, right? You might even say I’m financially better off, if you fill the gas tank before you put it back so it has more gas in it the next morning than it did when you took it.

Yet reasonable people, even people who think that software piracy or theft of music is OK, would draw the line at this sort of behavior. I doubt that very many folks would say that taking my cr for a joyride was acceptable; the “zero opportunity cost” argument would not hold up. Yet it’s the same argument that folks use to steal intangible things all the time.

Now, on to the horse that I have in this race.

In the past few days, intangible theft has affected me twice. First, my cable modem service was interrupted because my neighbor thinks that theft of service is OK. (Which, I suspect, will soon become a self-correcting problem; the police and the cable companies take theft of service seriously, and I started the ball rolling on a theft-of-service investigation this morning.)

Second, because I create intellectual property. I create content in the form of software, such as my game Onyx, and in the form of a great deal of writing on a number of diverse subjects.

Now, I like to think that I’m a reasonable fellow. I don’t much like the way the software industry works, so I give away a limited version of my game for free. I don’t like DRM and Draconian copy policies, so I license the pay version to people rather than to computers–if you buy the game, you’re free to put it on as many machines as you own, under whatever operating system you like, and the same serial number will work on all of them.

I believe that outreach, especially on subjects like non-traditional relationship and lifestyle choice, is important, so I permit anybody who wants to to copy any of the information on my Web pages, provided they credit me for it. My BDSM and polyamory pages are wildly popular, and I get several requests a month to copy part or all of the site elsewhere. Go for it! Do whatever you want. You don’t even need to ask me first. Seriously.

You want to print my stuff out and use it as a handout at a seminar? Be my guest! You want to translate it into other languages? Go right ahead! You want to put it on your own Web site? No problem! Just credit me as the author. That’s not an undue burden.

Yet, even that is apparently too much to ask for some folks.

Lat week, I discovered that large sections of my BDSM site were being used on the commercial, for-profit site of a prodomme who makes her living from her Web site, and they were posted without attribution. I sent her a nice email explaining that I was fin with her using the material, but I’d really appreciate credit. She responded by saying that she’d never heard of me or my Web site, and that she hadn’t taken the material from me, she’d taken it from another site.

I looked, and sure enough, she had–she’d lifted it from another site that had lifted it without attribution. From, get this, still another site that had lifted it without attribution.

No honor among thieves, I suppose.

So I’ve spent, over the last day or so, about four or five hours working my way up the chain and sending out copyright infringement notices. And I bet that over the next week I’ll probably be hearing from a bunch of pissed-off people.

That seems to be how it happens. People do geniunely seem to have a sense of entitlement to the intellectual work of others; when I’ve dealt with this kind of thing in the past, it’s shocking how often someone will become angry, as if to say ‘how DARE you tell me that I can’t take material you have created and use it on my own pay-for-access Web site!’. It’s not just me, either. In any dispute over intellectual property, the person whose work has been stolen is often cast as the villain–in ways that they are not if, for example, someone has his car taken.

Which is weird, and more than a little fucked up.

And sometimes, it’s by folks who really, really ought to know better. One of the Web sites that has lifted content from me belongs to the Triskelion Society, a well-known and generally well-respected BDSM organization. (Edit: As it turns out, the material was given to the Triskelion Society by a third party claiming copyright; they were blameless and have since removed the material.)

I’m sure that there will be folks who think I’m being unreasonably hard-assed about this. After all, my own site is free; what’s the harm in taking content from it for their own site? It’s not like I’m losing money, right?

In the end, I think that it comes down to respect. We (well, generally, most of us) respect the property of other people, and the labor of other people, but it seems that same level of respect does not extend to the intangible creations of other people. The zero-opportunity-cost argument displays an appalling lack of respect for other people’s effort and creation; it essentially boils don to “I want this, but I’m not going to pay for it, so I should have a right to have it anyway.” It’s even worse when it’s dressed in the language of self-righteous indignation; there are many music bootleggers who will rail against the RIAA as a corrupt, archaic, greedy institution that exploits its own members (which is true) and doesn’t pay its own artists (which is also true), but the difference between the RIAA and the misic pirates is that the RIAA believes artists should be paid a trivial pittance, whereas the music fans, incensed by this arrogance, seem to believe that the artists should be paid…nothing at all.

Now, me, I don’t ask for money; I merely ask that work I created should be attributed it to me. And apparently that’s too high a cost for some folks–even folks who use my content to build Web sites that they do charge money for.

But after all, they weren’t going to pay me for it anyway, so I haven’t really lost anything, right?

|

Your Social Dysfunction: Happy You’re a happy person – you have a good amount of self-esteem, and are socially healthy. While this isn’t a social dysfunction per se, you’re definitely not normal. Consider yourself lucky: you walk that fine line between ‘normal’ and being outright narcissistic. You’re rare – which is something else to be happy about. |

||||

|

||||

|

Take this quiz at QuizGalaxy.com

Please note that we aren’t, nor do we claim to be, psychologists. This quiz is for fun and entertainment only. Try not to freak out about your results.

|

…I was interviewed for the Mostly ITP podcast by Amber Rhea, who talked to me about Onyx, the sexuality map, and how the street finds its own uses for things;

…found out I’ve overrun my cell phone minutes last month by 831 minutes (ouch!);

…got my mage up to level 80 in World of Warcraft (Naxx and that sweet, sweet Tier 7 armor await!);

…discovered a prodomme who is using big sections lifted from my BDSM site on her page without attribution;

…and did a drastic overhaul of the look of the transhumanist section of my Web site (though the content remains the same).

It’s been a sleepy day today. Think I’ll go home and take a nap.

Seen at a grocery store while I was shopping with figmentj:

Yes, you’re seeing that right. It’s caffeinated hot chocolate. As in, hot chocolate with caffeine in it.

Have we as a society really reached the point where we can not face the day without putting drugs into everything we eat and drink?

One of my particular kinks I’ve quite liked for quite some time now is sexual objectification. Put most simply, it’s the creation of a psychological environment in which I’m using my partner for sexual gratification, or she’s using me for sexual gratification, without too much concern for the state of the other person’s sexual arousal or response (within whatever limits my partner and I have set out for the encounter).

I was talking about this with figmentj over the course of the last weekend, and she raised some interesting points that lead me to believe that I’m not really doing it right.

Now, to me, there is very little in the world that’s hotter than grabbing my partner, pushing her against the wall or down on the bed, and whispering in her ear “I’m going to take you now. It’s okay if you don’t want it; you can scream if you like.” Unless perhaps it’s a partner grabbing me by the hair, throwing me on the bed, and saying something similar.

Now, to me, there is very little in the world that’s hotter than grabbing my partner, pushing her against the wall or down on the bed, and whispering in her ear “I’m going to take you now. It’s okay if you don’t want it; you can scream if you like.” Unless perhaps it’s a partner grabbing me by the hair, throwing me on the bed, and saying something similar.

And to me, that’s what I’d consider objectification–the taking of my partner for my own sexual gratification.

And hers–which is where it kind of breaks down. For, as figmentj rightly pointed out, it’s only objectification if the person is reduced to the status of an object–that is, if the person’s feelings, experience, and humanity don’t enter in at all to what’s going on.

For me, the hottest thing about this kind of scenario is savoring the emotional state tat it creates in my partner, and seeing how my partner responds to being treated as a sexual object. If she’s not into it, on some level, it doesn’t work for me, because it’s precisely her responses that most get me hot.

Which is, when you get right down to it, not objectification. Her feelings and experience do enter into it; in fact, they’re precisely the point of the whole endeavor. It’s seeing how she reacts to being objectified that gets me off.

Which means, in the final analysis, I’m not really objectifying her at all.

Which is quite a conundrum, really. figmentj argues (cogently, I might add; I rarely prevail in a discussion like this with her) that what I’m doing may look like objectification, but it isn’t–not really. It’s something else. In order to be objectification, I’d have to have the same attitude toward her that I have toward an object, like a sex toy or something. Obviously, if I use some kind of sex toy, I don’t care at all about the experience from that sex toy’s perspective; it truly is an object. But since the central focus of the objectification I do with a partner is savoring her responses, and thinking about what’s happening from her perspective, then she isn’t an object at all, almost by definition.

So I’m clearly not doing it right. (Okay, that part is tongue firmly in cheek.)

That brings up another argument, one that was indirectly touched on by some of the folks who commented in the post on tattoos, porn, and respect for women, about what it means for porn to “objectify” women.

figmentj also argues, cogently, that much of mainstream porn is in fact objectifying (both to men and to women), but not for reasons that many folks of an anti-porn persuasion might think.

figmentj also argues, cogently, that much of mainstream porn is in fact objectifying (both to men and to women), but not for reasons that many folks of an anti-porn persuasion might think.

The standard objections to porn–at least the ones I hear most often–don’t really hold up to close examination. “It disempowers women.” Well, surely, if a woman has power, if she has control over her own body, then that control must extend to where, when, with whom, and under what conditions to have sex–including the choice to have sex while a camera is running, yes? “It degrades women.” This is an argument rooted in the notion that certain acts of and by themselves are inherently degrading, when nothing could be further from the truth. Degradation is contextual; it’s in the intent of the folks involved, not the act. Simple PIV intercourse? Not degrading when it’s mutual and consensual; degrading in the context of rape. Coming on a woman’s face? Not degrading when it’s mutual and consensual (yes, there are women who enjoy it, honest Injun); degrading if it isn’t.

And so forth.

The argument that figmentj raised, though, that standard, mainstream porn is objectifying not because sex is objectifying and not because sexual depictions are objectifying, but because the way it is scripted and filmed, with its surrealistically-proportioned actors who are as biologically implausible as a Barbie doll and its over-the-top, phony sound effects that make clear to anyone who’s ever actually had sex that the folks involved are not enjoying it, seems contrived and indeed even psychologically constructed to maximize the emotional distance between the viewer and the people involved.

In other words, much of mainstream porn–if there is such a thing–appears to be calculated to separate the depiction of sex as far as possible from the genuine responses of the people involved, and to be shot with folks who scarcely even look human, increasing that emotional distance still more. It doesn’t draw the viewer in; it doesn’t create an emotional connection between the scene and the viewer; its inauthenticity actually encourages the viewer not to empathize with the actors or even, really, consider them as human beings at all.

The objectification, then, takes place at the point at which the porn is consumed, not the point at which it is made. The real experiences of the actors becomes entirely irrelevant.

Now, this line of reasoning opens up several potential cans of worms–a whole bait factory of worms, in fact, not the least of which are

But those questions are not the real interesting part.

The real interesting part is the implication for porn in general.

The real interesting part is the implication for porn in general.

Now, I’m not that big a consumer of porn. The mainstream stuff in particular does little for me, for (among other things) exactly the reasons figmentj was talking about–the inauthenticity and the bizarre, weird-looking people in it.

On those occasions when I am interested in porn, my tastes tend to run to things that are a little more…umm, unconventional. I’m quite fond of the sort of stuff that kink.com produces–you know, bondage, S&M, humiliation play, that sort of thing.

Kink.com takes a lot of heat for the movies they produce. Take all the standard arguments against porn and crank them up to eleven; as a society, we’ve always been just fine with violence but a bit less OK with it when it’s combined by sex. A movie of a woman bound on all fours in an iron framework being simultaneously spanked and sodomized is, in short, bound to get folks talking, and not in good ways.

Yet the one thing you can say about this particular species of porn is that the reactions of the people involved are authentic.

Which is why I dig it. It works for me because the responses of the folks involved are authentic; it works for me for exactly the same reason that objectification play works for me.

And that means, at least for me, that this tied-down, cock-up-the-ass objectifying porn…isn’t objectifying at all.