This is the second part of a series of essays about GMOs, safety, and GMO labeling.

GMOs are a hot-button topic that inspire passionate emotions, and as with any hot-button topic people feel passionate about, there’s a lot of emotionally manipulative language being batted around on the subject.

While I was working on Part 1 of this essay series (which will, apparently, be the third part), I realized I need to back up a bit and talk about what a GMO is–hence, Part 0 of the series. I then realized I needed to back up a bit more and talk about how to spot emotional manipulation in rhetoric, which is why there’s a Part 0.5. In this essay, I’m using actual examples drawn from articles and essays on the Web, rather than hypothetical examples. Not all the examples are about GMOs specifically, but all of them show the types of emotional manipulation you’ll see in conversations about GMOs. (In gathering these examples for this essay, I took the hit to my sanity so you don’t have to.)

How to win friends and influence people

We all like to think of ourselves as reasonable, rational people, who do the research, evaluate evidence, and come to reasonable, rational conclusions.

The truth is different. Human beings tend to be emotional thinkers. We make decisions based on emotions, and then after we’ve made the decisions, we rationalize them. The decision comes first; the reason comes after. Yes, you do this. And you. And I do this, and you, and you in the back there too. (Think you don’t? Think again.)

That makes emotionally manipulative rhetoric extremely powerful. If you can influence a person’s emotions, it doesn’t much matter how faulty the rationalizations, how bogus the facts, or how shoddy the logic is–people will be powerfully motivated to preserve the emotional decision they’ve already made.

An excellent telltale that someone is rationalizing an emotional decision is goalpost-moving. If someone cites a fact or a study to explain why they believe something, and then that fact is shown to be false or the study is debunked, a rationalizer will not abandon the belief, but will instead move the goalposts, shifting to a different argument for the belief. This is why, as my mother is fond of saying, information by itself almost never changes attitudes.

Emotionally manipulative language is a rhetorical device designed to circumvent a person’s reason and lead to an emotional response. Once that emotional response has been triggered, it becomes really difficult for that person to change his mind, no matter how strongly the facts speak against his belief. I’ve blogged about this before; the “entrenchment effect” or “backfire effect” is a tendency of people to become more and more firmly entrenched in their beliefs when confronted with evidence that proves the belief wrong. And the beginning of the process is emotional.

So, let’s discuss some types of emotional manipulation.

Technique #1: Good guy/bad guy polarization

If you can make your own side out to be good guys, with noble motives and pure objectives, while simultaneously demonizing people holding contrary views as agents of pure evil, you can dramatically strengthen the emotional appeal of your argument.

This is a very common strategy in political debates, but it’s widely used outside politics as well. And to an average early twenty-first-century Westerner, there is no icon of absolute evil quite as vivid as the Nazis.

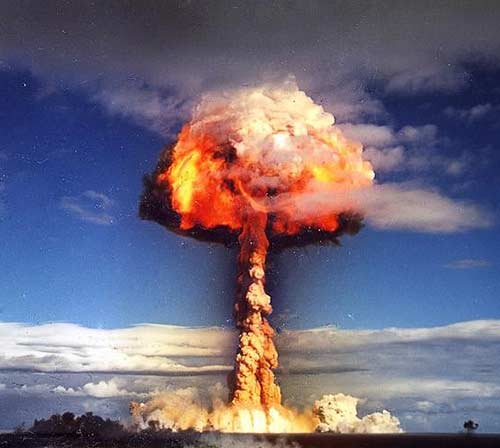

Some of the first folks to make their opponents out to be Nazis were the creationists, who painted EVIL-loution as the root cause of the Nazi Holocaust:

Creationist Ben Stein, the former actor famous as the principal in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and that annoying guy in the old Visine TV commercials, made an entire movie from the premise that evolutionary biologists and Nazis are the same. The device was so effective that everyone else jumped on the emotional manipulation bandwagon. Before long, we had Nazis in every cupboard.

The quality of the facts, as I said, doesn’t matter. Note, for example, the phrase “GMO (pesticide-laden) foods.” As I mentioned in part 0, a common misperception about GMOs and organic foods is that GMOs use lots of toxic pesticides and organic foods are pesticide-free. This isn’t true; all large-scale agriculture, including GMOs, conventional crops, and organic crops, uses pesticides. The list of approved pesticides for organic food includes natural, as opposed to “chemical” or “synthetic,” pesticides, but natural doesn’t mean less toxic. Indeed, the pesticides used on organic foods are, in many cases, quite a lot more poisonous to humans than the pesticides used on GMO or conventional crops. (I’ll get into this more in Part 2.)

The comparisons with Nazis are among the most blatant examples of this kind of good guy/bad guy rhetoric. I’ve seen sites that directly state all people who advocate for GMOs are “Nazi shills” who knowingly tell lies to make money. They are irredeemably evil; there’s no reasoning with such an agent of evil. Ergo, their arguments can be discarded without consideration at all.

But many folks cast their opponents as evil without invoking the Nazis. It’s often simply enough to brand an opponent or an entity “evil” and their motives utterly malign, which by implication suggests anything they have to say is not to be trusted.

Technique #2: The Grand Conspiracy

We love a good conspiracy. It’s in our blood. Conspiracy theories have been part of the Western social and moral fabric since Europeans ventured to the New World. They’re fueled by the Book of Revelation, with its description of a grand battle between absolute good and diabolical evil.

The players have changed: in the 1600s, people saw agents of the Spanish Empire everywhere. In the 1940s, the Soviets were plotting and scheming, hiding secret agents under every rock. Nowadays, especially among the political left, corporations engage in machinations to thwart the forces of Right and Good.

Conspiracies offer easy explanations to a world that’s often confusing or inexplicable. Why is AIDS turning out to be so challenging to cure, when we dealt with polio and smallpox so handily? It’s a conspiracy! Explanations of how the human immunodeficiency virus conceals itself from immune cells are complex and difficult to understand. It’s easier to believe we could cure it, but pharmaceutical companies are conspiring not to. Why do most scientists say that global warming is real and GMOs are safe, when these things don’t feel true? It’s because they’re conspiring to hide the truth!

A conspiracy mindset lends itself to easy manipulation; when you’re predisposed to conspiratorial thinking, anyone with a plausible-sounding conspiracy has an easy in. Evidence is not necessary; indeed, evidence that would disprove the conspiracy becomes proof of the conspiracy. And if a crank or a quack postulates some fanciful idea and is rejected by his peers, well, they’re part of the conspiracy too!

As we move into the second decade of the twenty-first century, conspiracies of Russkies have become passé; now, it’s conspiracies of scientists. It is, as I discovered, hard to keep all the science conspiracies straight–there are so many things scientists are supposedly being paid to keep secret that it’s amazing they’re not the wealthiest demographic on the planet.

Climate change deniers are some of the noisiest about a conspiracy of scientists. The latest twist on the conspiracy theory claims that these scientists are scheming to brainwash public school students.

There’s a reason climate change deniers tend to be concentrated on the political right, whereas political lefties, who deride the right for its anti-science bias, endorse equally anti-science ideas about vaccines and GMOs. When an idea becomes enshrined in our sense of self or political identity, it becomes very difficult to dislodge; challenging the idea is challenging to our sense of self. So a person who believes that government regulation is always bad and free enterprise is always good rejects the idea of human-caused climate change, because if climate change is actually happening, government intervention is the most plausible solution. (Interestingly, climate change deniers tend to be more willing to accept climate change if the evidence is provided along with proposed private-industry solutions.)

Similarly, a person who believes corporations are inherently evil and invariably seek to profit by harming people will be reluctant to accept things like vaccination or genetically engineered food, because they are created by corporations. The idea that corporations might create something beneficial doesn’t fit with that worldview; the perception that corporations are intrinsically harmful is difficult to let go of. When presented with evidence that contradicts an identity belief, it’s easy to see the evidence as part of a grand conspiracy, especially when the opposing side has already been declared “evil.”

The Grand Conspiracy creates a hermetically sealed echo chamber, impervious to evidence. Scientific evidence shows GMOs are safe? The evidence comes from the conspirators! There’s no evidence showing harm? The conspiracy has blocked it! People claim evidence of harm that is later debunked? Victims of the conspiracy! Once you’ve accepted the Grand Conspiracy, no confirming evidence is necessary and no disconfirming evidence is sufficient.

In reality, you simply can’t buy a conspiracy of scientists. For one thing, nobody–not even Big Oil–has enough money. For another, scientists are often a viciously competitive lot, their joy of discovery eclipsed only by their joy of proving another scientist wrong. The process of peer review is one part bar brawl, one part gleeful vindictiveness, and one part “I’m smarter than you are!”–all wrapped up with a bow and delivered by a dagger in the back.

You can, however, buy a handful of scientists, which is why it’s important to look at the total consensus of scientific thought. The tobacco industry was not able to buy all scientists, but they were able to buy one or two, who made enough noise to make it seem like there was no consensus on tobacco’s harmfulness. Big Oil wasn’t able to create a conspiracy of scientists to say lead additives in gasoline were safe, but they did manage to get one scientist to say it was safe–and then ginned up a faux “controversy” over its safety, even when the evidence was clear that lead additives were a bad idea. The antivax movement has managed to corral only a couple of scientists, the leading one being Andrew Wakefield, the man who accepted nearly a million dollars from law firms to try to manufacture evidence that vaccines cause harm.

There’s a lesson in here: When you have a couple of scientists on one end claiming something, and the entire scientific community on the other end saying something else, there might indeed be a conspiracy. But it’s probably not a conspiracy of the whole scientific community. It’s far more plausible that a couple of scientists are being paid off than the whole of the scientific establishment is!

Strategy #3: Scientific-sounding language: Baffle them with bullshit

Science and scientists are neither understood nor respected by many people. Yet despite this, people want the approval of science; they want the stamp of credibility that science gives their positions. Whether it’s religious bookstores with their books that claim science “proves” Christianity is true or quack medicines advertised with scientific-looking charts and words, science lends a cachet to even the most anti-intellectual ideas. I think of this as “science appropriation,” and I’ve written about it here.

Science appropriation becomes emotional manipulation when a person uses scientific-sounding words or concepts in order to try to make an argument appear legitimate when it is not. Often, the person making these arguments is counting on the intended audience not understanding the scientific terms. It’s emotional manipulation, not communication, because the words are used solely to provide an illusion of credibility. Often, the scientific-sounding words are grossly misused or even complete gibberish.

Here’s a great example:

These sentences are pure garwharbl. You can’t “choke nutrients at the DNA level”; DNA is simply a molecule, and by itself it isn’t even alive, much less in need of nutrients. And “mitochondrial cells”? Mitochondria are not cells; they’re parts of cells.

It’s a bit like if an oil company said, “Using our competitor’s gasoline chokes your car of fuel at the crankshaft level by depriving the distributor engines of oxygen.” It’s word salad, a mishmash of technical-sounding terms slung together at random without any appearance of comprehension of what the words mean, intended to evoke the feeling that the argument has the imprimatur of science.

This kind of argument is often used by people trying to argue that WiFi routers are dangerous.

Yes, wireless routers use the same “general frequencies” as microwave ovens. Scary! Or is it?

There’s an important bit that matters, and that’s how much energy there is. We understand this intuitively; your stove gets much hotter than, say, your electric blanket. One is dangerous at even a slight touch; the other keeps you nice and cozy. They’re both doing basically the same thing, but what matters is the total amount of energy they’re releasing. An electric blanket, a stove, and a blast furnace radiate electromagnetic energy at the same general frequencies, but how much they radiate is kind of important!

Strategy #4: False cause

Let’s say you were cruising the Internet one day, and you came upon this chart. Say the purple line shows rates of autism in the United States; say the red line shows the rate of GMO food sales in the United States. The lines match pretty well.

Would that support the idea that GMO food “caused” autism? (This is a real chart, by the way. More on it in a minute.)

There’s a thing you’ll hear in every college-level science course: “correlation does not mean causation.” But that’s not emotionally satisfying. Human beings are pattern-recognition machines. It’s one of the things our brains are optimized for. When it works, it helps us stay alive. We put a hand on a hot stove and get burned; heat causes us pain. Our ancestors hunted upwind of gazelle and the gazelle escaped; being upwind of prey animals leads to poor results.

Pseudoscience relies more than any other single tool on the principle of false cause–if two things occur together, one must cause the other.

You’ll often read things like this, almost invariably without sources for the statistics:

Nearly 100% of all serial killers have drunk milk at some point in their lives! You can not draw conclusions about one thing causing another thing until you’ve ruled out other causes, shown that absence of the first thing results in a corresponding decline of the second, and ideally linked thing one with thing two in a randomized controlled experiment. It helps if you can also propose a (testable) mechanism linking thing one to thing two.

Controlling for confounding factors–things that might actually be the hidden cause of something–is incredibly hard. For example, we used to believe that women taking hormone replacement therapy were at lower risk for cancer. But randomized trials showed that HRT actually increases cancer risk! So why did the initial data suggest lower risk? Because women who take HRT tend to be well-off, with good insurance coverage and good diets, and in good shape to begin with…in other words, they were in a socioeconomic group already at lower risk for cancer than people who were less well off.

Why might the percentage of people with chronic illnesses have increased in the last ten years? Many reasons: better diagnosis and better record-keeping (that is, maybe the incidence hasn’t increased but our awareness of it has); more coal-burning power plants (which produce pollution linked to a number of different chronic illnesses); increased numbers of people, especially children, living in poverty; the statistical aging of the population…it’s a complex question with a lot of variables and a lot of potential causes.

Emotionally, we don’t like complex questions with lots of variables and lots of potential causes. So that makes us easy to manipulate. “There are more sick people today, and people today are (getting more vaccinations|using microwave ovens|eating GMOs|spending more time in front of a computer|drinking more fluoridated water)! The connection is clear!

Oh, about that chart? It’s a genuine chart, but I’m afraid I have a confession to make. I fibbed a bit. The red line shows sales of organic food, not GMO food.

Strategy #5: Disgust

Disgust is one of the most primal of emotions. It appears to have a powerful survival value; it’s been linked to things that have a high likelihood of being associated with disease: spoiled food, bodily fluids, infection, that sort of thing. Because disgust is such a primal emotion, it can easily be enlisted to emotionally manipulate.

One of the easiest ways to do this is to create a link between something you’re arguing against and something disgusting. Once that emotional association is forged, it may prove remarkably resistant to the light of disproof.

The owner of the “Food Babe” website uses this strategy frequently, aggressively, and with great creativity:

They don’t actually put coal tar in tea, of course. This article was ranting about tea that’s made with “fractional distillation”–basically a technical term for “using heat to separate things.” Coal tar and gasoline are both made by fractional distillation, as are tea, herbal supplements, and many other things. Using heat to separate things is not exactly a controversial or newfangled idea.

Phrases like “coal tar in my tea?” are calculated to produce a feeling of disgust, an emotional response that helps cement the idea that this is something bad.

Children on schoolyard playgrounds often do this same thing, trying to gross one another out. Rumors of spider eggs in Bubble Yum got started this way, with kids trying to make each other feel disgusted; I first heard these stories when I was nine or ten.

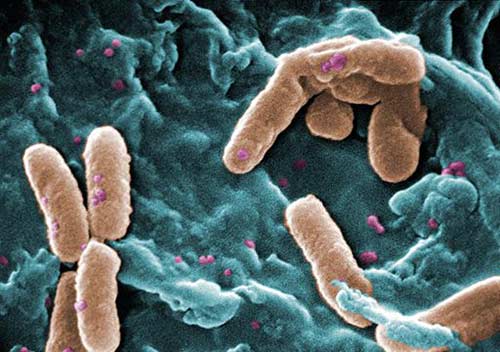

These same tactics are often employed against GMOs.

This is a modern variant on a gross-out tale as old as time; bubble gum (or, as one tale commonly spread in vegan circles has it, beef) have all been rumored to “leave material behind inside us.” Never mind the biological implausibility of it; the emotional response is what matters.

In many ways, the anti-GMO movement isn’t actually about health, or environmental concerns, or any of the other rationalizations people claim for being opposed to GMOs. It’s really an emotional food purity issue, no different except in detail from the obsession with “purity” that led to kosher or halal dietary restrictions. This is why conversations about GMOs tend to involve so much goalpost-shifting…the real objections are rooted in feelings of purity and disgust. So when one rationalization is knocked down, the goalposts shift and another takes its place. It’s also why so many anti-GMO arguments rely on evoking feelings of purity or disgust.

Strategy #6: Natural Nature, Made Naturally by Mother Nature

When you hear the word nature, what’s the first thing you think of? What’s the first thing you feel?

Is nature, to you, a serene, beautiful place where everything is in harmony and balance?

Or is it a place where every organism fights and claws its way to survival, and what looks like “balance” is really little more than a temporary stalemate?

In the excellent series of essays Panic-Free GMOs, Nathanael Johnson says,

You have one side that sees humans as fragile and dependent on maintaining the nurturing environment in which they evolved. The other sees humans as tough survivors of a fundamentally chaotic environment. One side sees huge dangers in technologies that alter our surroundings. The other sees technological advance as a defense against nature red in tooth and claw.

Over and over, this difference in emotional starting points creates division in risk assessment. People who see nature as a nurturing, benevolent force, full of springtime meadows and beautiful butterflies, tend to fear new technology; those who see nature as a battlefield, “red in tooth and claw,” tend to be less fearful of new technology. Where you stand on GMOs likely has more to do with how you feel about nature than about any evidence you’ve seen.

And this creates a very powerful lever for manipulating our emotions. People who are predisposed to see nature as kind and benevolent are also predisposed to the cognitive error known as the Appeal to Nature. Essentially, it’s the logical fallacy of believing that what’s “natural” is inherently good and what’s “unnatural” is bad. Evangelical church leaders rant that homosexuality is “unnatural,” antivaxers decry “unnatural” vaccines, and anti-GMO activists rail against “unnatural” manipulation of food (something I’ve seen someone do while eating a banana, which is irony in action if ever there was any).

The “natural gift from nature” folks tend to forget that cyanide, asbestos, deadly nightshade, Ebola, smallpox, and arsenic are all among nature’s gifts as well.

Hand-in-hand with natural goodness straight from nature comes what’s known as “chemophobia,” or fear of “chemicals.” The word “chemical” can conjure up powerful associations of strange, synthetic toxins, lurking in the environment ready to poison us.

This fear of “chemicals” and the associated belief that nature is “better” often leads people to fear “synthetic pesticides,” when in fact their natural variants are often far more poisonous and dangerous to humans.

Of course, everything is full of chemicals, because every substance that exists is, by definition, a chemical. The chemical dihydrogen monoxide is more commonly known by the common name “water.” The chemical 1,3,7-trimethyl-1H-purine-2,6(3H,7H)-dione 3,7-dihydro-1,3,7-trimethyl-1H-purine-2,6-dione is more commonly known as “caffeine.” Cyanocobalamin commonly goes by the name “Vitamin B12.” It’s all chemicals, and nature doesn’t care if those chemicals were made in a plant or a test tube–their actions depend on their chemical properties, not where they were born.

Strategy #7: Toxic Toxins that Poison Us with Toxins

The flip side of “nature is good” is “toxins are bad.” Like “nature” and “chemical,” the word “toxin” can carry emotional baggage. We don’t want to be exposed to toxic toxins! They’re toxic! And we certainly don’t want to massage toxic toxins through our hair!

The word “toxin” gets a lot of emotional bang per syllable, but the bit that’s often overlooked is it’s the dose, not the substance, that makes the toxin. If you drink enough of it, water is poisonous.

Fear of toxins has been a selling strategy for hundreds of years. You can browse the Internet or walk through a GNC store and find dozens of nostrums that claim to “detoxify” the body. Many of the arguments against GMOs come down to to toxic toxins of toxicity; for example, a lot of people will say that we should not eat GMOs because they are “sprayed with toxins like Roundup.”

The argument neglects to mention that organic and conventional foods are also sprayed with toxins–and indeed, the “natural” chemicals used on organic foods are very toxic indeed. (It’s a matter of no small amusement to me that Food Babe, known for her “toxic toxic toxic poison toxic toxic” rants, drinks alcohol, which…is a toxin.)

Not everything that’s toxic is toxic to everything that lives. The theobromine in chocolate is toxic to dogs but not people. Chemicals that are toxic to bacteria but not people are called by the name “antibiotics.” Synthetic herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides are often less poisonous to humans than their natural counterparts, because we can identify differences between people and insects or people and plants, then custom-tailor pesticides to act only on those specific differences. Roundup works by interfering with photosynthesis, so it’s extremely toxic to plants…but to humans, it is less toxic than baking soda!

There’s an area of special concern around Bt crops, which are engineered to create the natural insecticide called Bt. “I don’t want to eat plants that have insecticides in them,” I’ve heard people say. “It’s one thing when insecticides are sprayed on a plant, because I can wash it off. But if the plant makes it, I can’t wash it off. Toxic food!” Of course, this leaves aside the issue that organic farmers can and often do inject Bt directly into their plants, especially with vines.

But more importantly, almost all plants produce some sort of insecticides that can’t be washed off. The caffeine in tea and coffee, the eugenol in basil, the pungent sulfur compounds in onions and leeks that give them their aroma and flavor, the capsaicin in peppers, the allyl-thiosulfinate that gives garlic its smell and taste, the methanethiol in asparagus, the maysin in corn (yes, organic corn produces its own pesticide!), the terpenes responsible for the distinctive flavor of citrus fruits–all these are pesticides. When you’re a plant and you don’t want to be eaten, chemical warfare is one of your only alternatives! (Eventually, I’d love to compile a list of naturally-occurring pesticides in plants.)

And it’s…bad to use synthetic pesticides that are less toxic? The most toxic of the pesticides are…the ones we should use on “natural organic” foods? Aye, it’s a head-scratcher, it is!

Strategy #8: Rights! Your rights! Your rights are being violated!

A while back, I linked to an essay that describes the 6 Arguments Used by Science Denialists. To recap, the six are:

- Cast doubt on the science.

- Question the scientists’ motives and integrity.

- Magnify any disagreements among the scientists; cite gadflies as authorities.

- Exaggerate the potential for harm from the science.

- Appeal to the importance of personal freedom.

- Object that acceptance of the science would repudiate some key philosophy.

Item number five–appeal to the importance of personal freedom–is one of the standard tools in the toolkit of emotional manipulation.

The appeal to the importance of personal freedom is the backbone of the GMO labeling campaign. Advocates of labeling say we have a right to “know what’s in our food,” despite the fact that GMOs are not a “thing” that is put into food. The labeling initiatives tend to be quite fuzzy on what, exactly, needs to be labeled. If sugar is made from a GMO sugar beet or oil is produced from GMO soy, the result is pure sugar or pure oil, with no DNA, proteins, or anything else that has anything to do with GE technology in it. Yet labeling advocates claim such things should be labeled–even though there is nothing in it that has anything to do with the GMO source of the product.

Another form of this same emotional manipulation occurs when sinister forces, such as evil food producers, are accused of using you as a “guinea pig,” experimenting on you without your consent. You are being experimented on, and denied your freedom to live a non-guinea-pig lifestyle!

Strategy #9: X is used as a Y

This is tangentially related to provoking an emotion of disgust, but it’s more specific.

Say I told you that a common food preservative was manufactured from a deadly poison gas used as a chemical weapon in World War I. Or I told you that one of the most common ingredients found in prepared food is an industrial solvent also used in floor cleaners and paint thinners.

Both of those statements would be true. The most common preservative is ordinary table salt, which is sodium chloride–a combination of sodium and chlorine. Chlorine was used as a chemical weapon in WWI. And one of the most common ingredients in all foods is indeed an industrial solvent used in floor cleaners and paint thinners: water.

That’s the essence of the “X is used as a Y” argument: take an ingredient in food that also has some other use, and trigger an emotional response by juxtaposing the two uses. Eww! You want to EAT chemical weapons and floor cleaner??!

So what about it? Does this ingredient keep hemoglobin in your blood from carrying oxygen? Sure, if you eat a lot of it–and water prevents nerves from firing and stops your heart from beating by diluting the sodium and potassium ions that allow nerve cells to work, if you drink enough of it. Those nuances, though, aren’t relevant; the aim is not education, but manipulation.

When I was growing up, my mother always used to say “education is not the solution if ignorance is not the problem.” (She said a number of other cool things too; all in all, my mom is pretty awesome.)

A lot of folks believe that people are easily swayed by pseudoscientific ideas because they lack the facts, and that providing access to those facts will solve the problem. This is the “deficit model” of science communication. This model has a lot of flaws, chief among them the presumption that people make rational decisions based on the best information available to them.

In fact, people often make decisions for emotional reasons, then rationalize those emotional decisions after the fact by inventing (or accepting) plausible-sounding ideas that confirm their emotional decisions. This is why emotional manipulation is so effective, and why discussions of emotionally charged topics like vaccination and GMOs has to include conversation about emotional manipulation.

Now that that’s out of the way, the next part of this series will actually discuss the facts around GMOs, I promise.

Note: This blog post is part of a series.

Part 0 is here.

Part 0.5 is here.

Part 1 is here.

Part 2 is here.

Part 3 is here.

Like this:

Like Loading...

A particularly pernicious variant on this “women-as-victims” narrative is circulating amongst folks who are generally politically liberal and see themselves as allies of women, but still face discomfort about porn and sex work: Well, yes, women can and do freely choose to go into porn or sex work, but, you see, not abuse porn like what you see at

A particularly pernicious variant on this “women-as-victims” narrative is circulating amongst folks who are generally politically liberal and see themselves as allies of women, but still face discomfort about porn and sex work: Well, yes, women can and do freely choose to go into porn or sex work, but, you see, not abuse porn like what you see at  The starvation model of sex work starts with the assumption that it is hard to find people who want to do porn or sex work. A reasonable person wouldn’t make that choice, except through coercion or the most dire of necessity. Therefore, to feed the demand for sex workers and porn performers, there must be coercion and abuse.

The starvation model of sex work starts with the assumption that it is hard to find people who want to do porn or sex work. A reasonable person wouldn’t make that choice, except through coercion or the most dire of necessity. Therefore, to feed the demand for sex workers and porn performers, there must be coercion and abuse. Psychologists often talk about a quirk of human psychology called the fundamental attribution error. It’s a bug in our firmware; we, as human beings, are prone to explaining our own actions in terms of our circumstance, but the actions of other people in terms of their character. The standard go-to example of the fundamental attribution error I use is the traffic example: “That guy just cut me off because he’s a reckless, inconsiderate asshole who doesn’t know how to drive. I just cut that car off because the sun was in my eyes and there was so much glare on the windshield I didn’t see it.”

Psychologists often talk about a quirk of human psychology called the fundamental attribution error. It’s a bug in our firmware; we, as human beings, are prone to explaining our own actions in terms of our circumstance, but the actions of other people in terms of their character. The standard go-to example of the fundamental attribution error I use is the traffic example: “That guy just cut me off because he’s a reckless, inconsiderate asshole who doesn’t know how to drive. I just cut that car off because the sun was in my eyes and there was so much glare on the windshield I didn’t see it.” I would like to propose that there is another bug in the operating firmware of humanity, similar to the fundamental attribution error. Call it the fundamental construction error, if you will. We as human beings re-construct the world in our own image, assigning our own values, ideas, squicks, taboos, likes, and dislikes to the great mass of humanity as a whole. “Nobody likes,” “everybody wants,” “nobody would,” “everybody thinks”–all statements of this class can most properly be understood to mean “I don’t like,” “I want,” “I wouldn’t,” and “I think.”

I would like to propose that there is another bug in the operating firmware of humanity, similar to the fundamental attribution error. Call it the fundamental construction error, if you will. We as human beings re-construct the world in our own image, assigning our own values, ideas, squicks, taboos, likes, and dislikes to the great mass of humanity as a whole. “Nobody likes,” “everybody wants,” “nobody would,” “everybody thinks”–all statements of this class can most properly be understood to mean “I don’t like,” “I want,” “I wouldn’t,” and “I think.”

As many folks who’ve read this blog over the years know, I am, among many other things, a game designer. I’ve developed a game called Onyx, which I’ve maintained and sold since the mid-1990s. Onyx is a sex game. It’s designed for multiple players, who move around a virtual “game board” buying properties. When another player lands on your property, that player can pay rent or–ahem–work off the debt.

As many folks who’ve read this blog over the years know, I am, among many other things, a game designer. I’ve developed a game called Onyx, which I’ve maintained and sold since the mid-1990s. Onyx is a sex game. It’s designed for multiple players, who move around a virtual “game board” buying properties. When another player lands on your property, that player can pay rent or–ahem–work off the debt. I was told that BPS would no longer work with me, but their parent company, Vantiv, would be happy to give me a merchant account. Vantiv’s underwriters, I was told, had looked at my Web site and had no problem with its contents.

I was told that BPS would no longer work with me, but their parent company, Vantiv, would be happy to give me a merchant account. Vantiv’s underwriters, I was told, had looked at my Web site and had no problem with its contents. The goal of Operation Choke Point is to pressure businesses in morally objectionable fields out of business, by leaning on the banks that provide services to those businesses. If you can’t get banking or credit card services, the reasoning goes, you can’t stay in business. So the DoJ is approaching commercial banks, telling them to close accounts for individuals and businesses in “objectionable” industries.

The goal of Operation Choke Point is to pressure businesses in morally objectionable fields out of business, by leaning on the banks that provide services to those businesses. If you can’t get banking or credit card services, the reasoning goes, you can’t stay in business. So the DoJ is approaching commercial banks, telling them to close accounts for individuals and businesses in “objectionable” industries. In addition to adult businesses, Operation Choke Point targeted small gun and ammo retailers. And there’s a small, cynical voice inside my head that whispers, if they had contented themselves with going after people like me–people who make or sell things related to sex–would anyone have cared? The right-wing blogosphere is filled with angry rants about Operation Choke Point, as well it should be…but none of the angry rants mention adult businesses or porn. They all focus on guns. And I just really can’t make myself believe that the people rising up against the program have my interests at heart. If it were just me, I believe we wouldn’t hear a peep out of them.

In addition to adult businesses, Operation Choke Point targeted small gun and ammo retailers. And there’s a small, cynical voice inside my head that whispers, if they had contented themselves with going after people like me–people who make or sell things related to sex–would anyone have cared? The right-wing blogosphere is filled with angry rants about Operation Choke Point, as well it should be…but none of the angry rants mention adult businesses or porn. They all focus on guns. And I just really can’t make myself believe that the people rising up against the program have my interests at heart. If it were just me, I believe we wouldn’t hear a peep out of them.