[Note: This essay originally started out as an answer on Quora.]

If, God help you, you ever read incel or “men going their own way” forums, which I have done, you frequently find a complaint—

Well, hang on, wait. You frequently find many complaints, because that’s pretty much all the incels and MGTOW folks do: whine and complain. One of those complaints you’ll often see is that “men are losing their rights” thanks, of course, to those evil feminist women, hell-bent on stripping men of their natural God-given rights.

The standard answer to this particular whine is, of course, “egalitarianism doesn’t mean you lose your rights, it means women gain rights.” Which is true as far as it goes, but the fact is, yes, men have lost rights because of feminism. In fact, you can look at the changing legal landscape in the United States over the past century and point to specific legal rights men once had that they don’t any more, directly because of feminism.

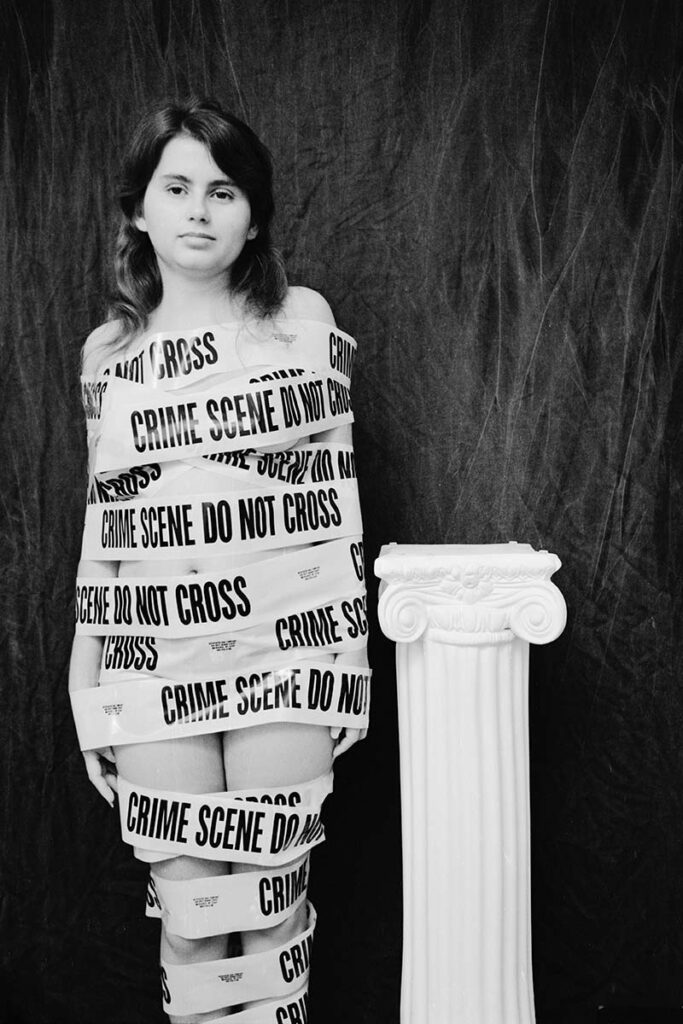

Photo by author

I was born in the 1960s, so I’ve lived through the rise of modern feminism.

Men have lost rights, both legal and civil, due to the rise of women’s rights.

Here’s a partial list of rights and privileges I as a man have lost just in my lifetime due to women’s rights:

- The right to rape my wife without being prosecuted. Before 1974, marital rape was legal in every state. It was banned in Delaware and Maryland in 1974, but remained legal in other states until 1993.

- The right to control my spouse’s money. Until the early 1960s, women could be barred from opening bank accounts at all without a male co-signer. Until 1974, married women could be barred from opening a bank account; the bank account was always in the man’s name, and the man had control. Until 1974, women could be barred from having a credit card in their own name.

- The right to sexually harass at work. Until 1980, sexually harassing women in the workplace was legal.

- The right to have certain jobs reserved only for men. Until 1970, it was legal for employers to reserve certain jobs as “men only” even if the sex of the person in the job had nothing to do with the job. Advertising designer, newspaper reporter, and many other jobs were frequently reserved as “men only.”

- The right to hire only single women. Before 1960, many employers banned married women—you had to be single to get a job, and you were fired if you got married.

- The right to control estates. Until 1971, women were banned from administering estates and could be passed over for inheritance at the whim of the estate administrator.

- The right to prosecute women as “public scolds.” Until 1972, men could take legal action against women for “being quarrelsome or public scolds.” The last public scold law was struck down in 1972.

- Control over women’s housing. Until 1974, landlords could refuse to rent to women.

- Control over women’s healthcare. Until 1976, laws in many states said that a woman could not seek certain forms of healthcare without the signature of their husband or a male guardian.

- Control over women’s money part II: Until 1981, married men in Louisiana has complete control over their wives’ money and property under a law called—get this—the Louisiana Head and Master Law. It was finally struck down in 1981.

How do I, as a man, deal with that?

Simple: I don’t want to rape my wife. I don’t want to control her money, control her doctor’s visits, or have her arrested as a scold.

In other words, why am I losing my rights? Because the rights I’ve lost are rights that men should never have had in the first place.

That’s the pesky asterisk in “men are losing rights*”. And it’s a different argument than “ha ha ha LOL shut up you haven’t lost any rights.” Men have lost rights. Unpacking why, and whether we shoud’ve ever had them to begin with, is a different conversation, and one I think we need to be willing to have if we are to deconstruct the weird entitlement of the manosphere.