Outside my bedroom window this morning.

Outside my bedroom window this morning.

In response to this post I made about the intersection of disability and transhumanism, illicitlearning posted a link to a YouTube video on exactly the same subject, that discusses some facts I wasn’t aware of.

The entire video is over an hour long, so for that reason I’m not going to embed it here. I do recommend that anyone interested in ethics, body modification, transhumanism, functional changes to the body, agency, bioethics, or the ownership of the self watch it, however. It’s probably not safe for work–there are pictures and descriptions of forms of body modification some folks might not approve of–but it’s good to watch regardless.

You can find the YouTube video here.

The person in the video is Quinn Norton, a journalist who’s long been interested in both body modification and transhumanism. She’s one of the people who first experimented with subdermal rare-earth magnet implants that I talk about here.

One of the things that surprised me to learn from this video is just how profoundly fucked-up our system of bioethics–and I use the term “ethics” in there only loosely–is in this country.

We have the capability to do some really neat things, and we’re on the cusp of learning to do some even cooler things. We can, for example, exploit the brain’s plasticity to create new senses (as with the aforementioned implanted magnets) or to map one sense onto another (as with experimental devices that allow people to see by mapping images onto the tongue with electric currents).

We have the capability to do some really neat things, and we’re on the cusp of learning to do some even cooler things. We can, for example, exploit the brain’s plasticity to create new senses (as with the aforementioned implanted magnets) or to map one sense onto another (as with experimental devices that allow people to see by mapping images onto the tongue with electric currents).

We’re closing in on more interesting things still. For example, one area of nanotech research involves respirocytes, which are tiny machines designed to do what red blood cells do by carrying oxygen to and taking carbon dioxide away from the cells of our body. The trick is that they are thousands of times more efficient, and if they work as projected, would allow someone injected with them to do things like hold their breath for half an hour, run at full speed without breathing for ten or fifteen minutes, and even survive with their heart stopped for thirty minutes or so.

And you know what? All this stuff is considered “unethical”–and much of it is illegal.

Before I get off on the rest of this rant here, I’d like to start with a basic premise from which the entire rest of my argument against this sort of nonsense flows, and that is the value of agency.

Agency–the notion that each of us is a self-determining, self-aware individual, uniquely positioned to choose for ourselves what we do with our own bodies–is, I believe, the most basic of all moral principles, and the one from which all other moral principles flow. Things that we all agree are immoral, such as murder, kidnapping, rape, or torture, ultimately grow from the notion of agency. Each of us is responsible for the consequences of our decisions (else there can be no morality), and each of us has the ultimate right to control of our own bodies (the right which is violated when another person deprives us of our liberty or our life).

In the final analysis, I do not believe any credible system of ethics can ignore or diminish the principle that the first and most basic of all moral principles is the idea that we have the right to choose for ourselves what we do with our bodies.

So. Onward.

According to the American Medical Association’s Code of Ethics, there are many techniques and procedures that are considered “unethical” across the board. Among these are “augmentation” technologies–technologies intended or designed to provide someone with greater-than-human-normal abilities or senses.

An example? Cochlear implants. These implants are often used to cure one of the most common forms of deafness, and for this use, they are considered both legal and ethical. The implant is a tiny electronic gadget implanted deep in the ear anal, and connected directly to the auditory nerve. They’re implanted into tens of thousands of deaf patients to restore hearing.

But…

A cochlear implant which offers a deaf person some kind of new ability or functionality that a “normal” person does not have is considered unethical across the board. For example, a cochlear implant that had BlueTooth functionality, to allow its user to directly access a cell phone or a computer? Unethical. An American doctor who implanted such a thing would lose his license. A cochlear implant designed to be implanted in a person with normal hearing, to extend the range of his hearing? Also unethical.

And it gets worse.

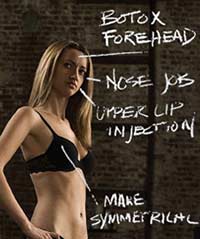

In the United States, it is considered a breach of medical ethics for a plastic surgeon to change someone’s appearance outside the socially accepted standards of physical beauty.

In the United States, it is considered a breach of medical ethics for a plastic surgeon to change someone’s appearance outside the socially accepted standards of physical beauty.

Read that again and think about it. In the United States, it is considered a breach of medical ethics for a plastic surgeon to change someone’s appearance outside the socially accepted standards of physical beauty. Medical ethics are dictated by socially accepted standards of physical attractiveness. It is perfectly legal, and perfectly ethical, for a plastic surgeon to put silicone into a woman’s tits to make them bigger (because social standards of beauty favor big tits), but it is considered unethical (and in most places, illegal) for a plastic surgeon to do something like pointed ears; a surgeon who does so risks loss of his license, prison, or both.

Which is pretty damn stupid, if you ask me.

In practice, what that means is the folks who want to get many kinds of body modifications done, from aesthetic mods like pointed ears to functional mods like implanted magnets, must go to unlicensed body-mod artists without formal medical training, who are not medical doctors and who do not have access to anaesthetics, antibiotics, or other basic medical tools. All because the results either give them some functionality outside the “human norm” or take their appearance away from “socially accepted standards of beauty.”

The people who practice the art of body modification live under constant threat of legal action. In some states, such as California, they are considered “unlicensed medical practitioners” and are subject to arrest and prosecution if they are caught. In other states, such as Oklahoma, a person willing to do something as simple as tattooing must pay a $100,000 cash bond to do so legally (and that’s actually a concession to fans of body art; until 2006, tattooing was illegal everywhere in the state.

Now, you might not be into tattoos or pointed ears. Personally, I think they can look cool on the right person, but whatever. That’s not the point. The point is that we as a society have determined that you should only be able to control the way your body looks if the result is what other people would find attractive, and I frankly think that’s an appalling and immoral approach to the question of medical ethics.

Look, this is really simple. My body belongs to me; your body belongs to you. Our appearance is not subject to vote. And yet that’s exactly what we have–a system whereby if enough people think that something (big tits) is attractive, then plastic surgeons are ethically permitted to give women big tits, but if there aren’t enough people who think something else (pointed ears) is attractive, then plastic surgeons are barred from giving folks pointed ears.

It’s stupid enough to live in a society that tells people, every day, in a hundred thousand different ways, that there’s only one way you are “supposed” to look, but to write that notion into professional ethics and law is stupid beyond belief. We claim to be a society that values plurality, diversity, and individual control over our own lives, yet in the single most basic, fundamental form of individual control of all, individual control of our own bodies, we have adopted a herd mentality and then elevated that heard mentality to the level of ethical absolute.

It’s stupid enough to live in a society that tells people, every day, in a hundred thousand different ways, that there’s only one way you are “supposed” to look, but to write that notion into professional ethics and law is stupid beyond belief. We claim to be a society that values plurality, diversity, and individual control over our own lives, yet in the single most basic, fundamental form of individual control of all, individual control of our own bodies, we have adopted a herd mentality and then elevated that heard mentality to the level of ethical absolute.

“I like big tits, so doctors are permitted to perform dangerous and massively invasive surgery to give women big tits. I don’t like pointed ears, so doctors are not permitted to perform relatively trivial, simple procedures to give people pointed ears.” Someone explain to me exactly how this is “ethical”? When was it, exactly, that common tastes dictated ethics?

And those standards of “socially acceptable beauty” are themselves toxic and unrealistic. A lot of folks might not like the thought of people getting pointed ears, but how do you explain the saga of Melanie Berliet, an attractive 27-year-old model and Vanity Fair writer, who for her piece on cosmetic surgery visited three plastic surgeons, who complied a lengthy, expensive, and medically invasive list of “improvements” they recommended for her? A lot of people talk about how toxic and unrealistic social standards of female beauty are, but when you take it to the ludicrous extreme of thinking that a very attractive woman by ay standards could benefit from surgical “improvement,” but that functional or unconventional body modification is inherently wrong, what exactly does that say about social standards?

Folks, this is fucked up beyond all human reckoning.

A great deal of the current legal landscape regarding body modification, particularly “enhancement” and “human norms,” can be traced to the opinions of a few people, notably among them Leon Kass and Francis Fukuyama.

These two people were among the eighteen appointed by George W. Bush to the president’s Council on Bioethics when Bush took office. The Council on Bioethics is an Administrative cabinet designed to advise the President on the ethical issues surrounding medicine and biotechnology, and as such its goal, at least nominally, is to act as an ethical voice in considerations including legislation, regulation, and research funding in biotechnology.

These two people were among the eighteen appointed by George W. Bush to the president’s Council on Bioethics when Bush took office. The Council on Bioethics is an Administrative cabinet designed to advise the President on the ethical issues surrounding medicine and biotechnology, and as such its goal, at least nominally, is to act as an ethical voice in considerations including legislation, regulation, and research funding in biotechnology.

And who, exactly, are these people?

Leon Kass, the head of the Council under Bush, is an ardent foe of new biotechnology, particularly research involving human reproduction, longevity, and augmentation. He is the architect of Bush’s stem-cell research ban, and lobbied Congress unsuccessfully to pass a ban on research aimed at improving human lifespan on the grounds that death is “necessary and desirable end” and “Christians already know how to live forever.” He opposes in-vitro fertilization on the grounds that it is an affront to human dignity (an argument which I must admit makes no sense at all to me) and that it obscures moral truths about the essence of human dignity (which basically sounds like handwaving: “It seems yucky to me, so I’ll blather about moral truth to conceal the fact that I have no cogent arguments save for the fact that it seems yucky to me”).

In fact, Kass even explicitly acknowledges this “yuck factor.” He calls it “the wisdom of repugnance,” and says that anything we see as “yucky” is, on its face, inherently immoral–by which definition, things like organ transplants (derided with disgust as “doctors cutting up corpses and sewing bits of dead people into live people” when it first started to develop). Many things seem yucky when they are new, but with familiarity come to be recognized as the lifegiving boons that they are.

Francis Fukuyama is a political economist who somehow believes that his knowledge of politics and economic issues makes him fit to hold a cabinet-level position on the ethics of biotechnology. He has written a book, “Our Posthuman Future,” in which he labels transhumanism as the most dangerous idea that has ever developed. He’s also noteworthy for another popular book, “The End of History and the Last Man,” in which he argues that the progression of history is over and that free-market democracy is the ultimate of all political and social systems. He’s one of the leaders of the neoconservative movement, and was one of the architects both of the Reagan Doctrine and of the Iraq war.

Francis Fukuyama is a political economist who somehow believes that his knowledge of politics and economic issues makes him fit to hold a cabinet-level position on the ethics of biotechnology. He has written a book, “Our Posthuman Future,” in which he labels transhumanism as the most dangerous idea that has ever developed. He’s also noteworthy for another popular book, “The End of History and the Last Man,” in which he argues that the progression of history is over and that free-market democracy is the ultimate of all political and social systems. He’s one of the leaders of the neoconservative movement, and was one of the architects both of the Reagan Doctrine and of the Iraq war.

Now, you might think it strange that a free-market neocon who favors individual and free-market choices would argue that people should not be free to choose to modify themselves if they want to, and that the free market should not be permitted to offer that choice. Honestly, I’ve never been quite able to wade through his logical contortions in supporting this notion, but they seem to come down to “I want modern American democracy to be the be-all and end-all of human development, and radical new biotech that offers to change human beings too much might upset that notion and lead rise to new social and political systems that I can’t even imagine, and I think that would be bad, so we should ban any new biotechnology that could upset the applecart.”

Which strikes me as being a bit like a Roman senator saying “Rome is the pinnacle of human economic and political triumph, so we should ban any new technologies that might lead folks away from the Roman model of civilization.” And that, were it put into reality, would mean that you and I would not be having this conversation, since an instantaneous globe-spanning communication network was most definitely not part of the Roman model.

What Mr. Fukuyama doesn’t realize is that history never ends. The United States is no more the end of history than the Roman Empire was, and that’s a good thing.

It seems to me that these people–tho opponents of transhumanism, the ethics board of the American Medical Association–live in a tiny, conformist world, terrified of change and intolerant of diversity. It’s ethical to change someone’s appearance, but not if the change doesn’t match conventional standards of beauty. It’s ethical to tell women that they need bigger tits and fuller lips, but it’s not ethical to let them make their own choices about their bodies. It’s ethical to implant a device to let a deaf person hear, but not if it lets him hear better than I can.

The bionic man from the TV show The Six Million Dollar Man is, under our current legislative and ethical system, considered an abomination, and the doctors who worked on him would in real life lose their jobs, even if they improved his standard of living. We should help the disabled, but not, y’know, too much.

In the United States, we have long associated “morality” with “sex.” This nation can boast such moral luminaries as Charles Keating, the anti-porn moral crusader who made movies and advised President Reagan on moral issues before embezzling $1.2 billion dollars from a savings and loan under his control, touching off a nationwide financial crisis that threatened to rob working families of their lifes’ savings…but he was deeply concerned with morality, you see.

Even in bioethics this association continues. We have a medical community whose ideas about medical ethics are predicated on the fact that any change that makes a woman more fuckable to the general population is good; any change that makes a woman less fuckable to the general population is bad.

We are also deeply fearful as a society. We shun the disabled and favor medical technology that makes them more like us–but only so long as it keeps them in their place and doesn’t make them, y’know, better than us.

At each step along the way, we construct ethical systems that are the antithesis of agency, that seek to take away control of our bodies from each individual and instead place that control at the mercy of the common, socially accepted standard of beauty.

And I think that it’s about time we start re-thinking that approach to morality.

Via creekracer

….here’s a great one from over on anansi133‘s blog.

“Disabled” and “not disabled” are not binary states, and increasingly, we’re learning to make the distinctions irrelevant. I think we’re approaching the time when replacements to parts of our body, instead of being clunky and inferior in every way to the original, are actually improvements; this is already happening in some specific niches, such as in track and field, where the International Olympic Committee is reluctant to allow legless athletes to compete with normal athletes because of the perception that sprinting prosthetics are superior to natural legs, and give the nominally “disabled” athlete an unfair advantage.

Personally, I’d like to see an athletic event similar to the original Can-Am racing event, designed to push technology right up against its limits; the rules might be something like “any augmentation or prosthetic is permissible as long as it does not contain its own power source and is powered completely by the body of the athlete who wears it.” I bet we’d see some really interesting stuff (four-second hundred-yard dash, anyone?). But I digress.

Anyway, I think the intersection of disability and transhumanism is kind of fascinating, and I find it interesting that it may end up being nominally “disabled” people who lead the way.

So last night I was reading my friends list, and ran into the video I’ve posted below on drjon‘s journal.

Now, this video is about racism, but touches on a really important idea that I think extends way, way beyond conversations about race. On the subject of racism itself, I have little to add beyond what the video already says, so I’ll leave that alone.

The video is by a guy who calls himself Jay Smooth. He has a Web site and a YouTube channel, and he’s articulate and smart and funny and before you know it I’d been sucked down the Intertubes and had wasted two hours watching all his stuff.

So thanks, drjon, that’s two hours I’ll never have back.

Anyway, the video is short and is worth watching, and I’ll put it here so you can see what I’m talking about before I move on to the point that extends beyond racism and race.

The distinction between “what he did” and “what he is” is important. It’s something that trips us up as human beings all the time. It’s the thin edge of the wedge that leads to mind-reading behavior, false assumptions, broken expectations, and all manner of other ills that plague us. And it’s a really, really easy mistake to make.

Human beings are a storytelling species. We tell ourselves stories all the time, every day, without even being aware of it. These stories help us to try to make sense of the actions of other people. Indeed, we even invent stories that we tell ourselves in order to explain our own behavior, as vividly illustrated in one famous series of studies of people whose corpus callosum had been split.

A quick recap for folks who are not neurology geeks: The corpus callosum is a thick bundle of nerves that connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain. If this is damaged or cut, as used to be done to treat a certain kind of epilepsy, the hemispheres can’t communicate directly with each other. Each hemisphere controls one-half of the body and sees one-half of the visual field, but language usually exists only in one hemisphere, not both; when the corpus callosum is cut, it’s almost like you have two different brains in one body, but only one of the two can talk.

A quick recap for folks who are not neurology geeks: The corpus callosum is a thick bundle of nerves that connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain. If this is damaged or cut, as used to be done to treat a certain kind of epilepsy, the hemispheres can’t communicate directly with each other. Each hemisphere controls one-half of the body and sees one-half of the visual field, but language usually exists only in one hemisphere, not both; when the corpus callosum is cut, it’s almost like you have two different brains in one body, but only one of the two can talk.

Scientists have had a ball studying folks like this; it’s great fun. One common experiment involved showing things designed to provoke a reaction to the right hemisphere, which usually lacks language, then asking the person why he was reacting the way he did; the left hemisphere had no clue what the right hemisphere was seeing, but the person would nevertheless offer up all kinds of stories to explain his reaction. An even better experiment involved showing different images to the two hemispheres, such as a snowbank to the right hemisphere and a chicken to the left hemisphere, and then asking the person to point with his left hand at an object relevant to the thing he was seeing. The right hemisphere controls the left hand, so the right hemisphere, which was seeing an image of a snow bank, would point to a snow shovel. The left hemisphere, which was seeing a chicken, had absolutely not the foggiest idea why he was pointing to the shovel, but when he was asked “Why did you point to a shovel?” he’d say “Well, because I see a chicken, and you need to use a shovel to clean up chicken manure.”

In other words, he invented a story that was total fabrication to explain his own actions, without even being aware that he was inventing a story.

We all do this, all the time, and unless we guard against it, it can really distort our perceptions of other people. Every time we say “So-and-so did this because so and so is a ___”, we’re falling into this trap.

The fact is, unless we are mind readers (or unless someone actually explicitly says why he did something), our stories about other people’s motivations are just that–stories. We fabricate these stories based on our own projections and our own ideas.

Worse, we’re not even fair about it.

In the book How We Know What Isn’t So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life, Thomas Gilovich talks about the self-serving nature of the stories we tell. Sociologists love this stuff, and (naturally) have done a number of experiments illustrating this, by asking people who’ve done something why they did it, and then asking people who are watching someone else do the exact same thing why that person did it.

In the book How We Know What Isn’t So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life, Thomas Gilovich talks about the self-serving nature of the stories we tell. Sociologists love this stuff, and (naturally) have done a number of experiments illustrating this, by asking people who’ve done something why they did it, and then asking people who are watching someone else do the exact same thing why that person did it.

Invariably, people will offer situational explanations for their own behavior–“I did it because of the situation I was in”–but will offer personal explanations for other people’s behavior–“He did it because he is a worthless, good-for-nothing bastard who doesn’t care about me.”

For example, we’ve all cut someone off in traffic, and we’ve all seen someone cut us off in traffic. If you ask a person “Why did you just cut that guy off?” the person will probably offer you a situational explanation, like “The sun was in my eyes, and all the glare on the windshield made it impossible for me to see him.” But if you ask that exact same person “Why did that driver just cut you off in traffic?” that person will probably say “Because he is a reckless, careless idiot who doesn’t give a damn about anyone else on the road.”

In other words, to get back to the video, people don’t talk about what that other driver did, they talk about what that other driver is.

That’s a dangerous road to walk down, talking about what other people are. Projections of the motivations of others can get you in trouble fast.

But we do it all the time. And it’s not just with other drivers; we do it in politics, in relationships, everywhere.

“You voted for McCain because you’re a religious zealot who wants to see the government overthrown and replaced with a totalitarian militant theocracy.” “Oh, yeah? You voted for Obama because you’re an anti-capitalist tree-hugger who wants to destroy private enterprise!” This is what happens when we think we can tell what people are by looking only at what they did, and it’s an embarrassment.

“You voted for McCain because you’re a religious zealot who wants to see the government overthrown and replaced with a totalitarian militant theocracy.” “Oh, yeah? You voted for Obama because you’re an anti-capitalist tree-hugger who wants to destroy private enterprise!” This is what happens when we think we can tell what people are by looking only at what they did, and it’s an embarrassment.

Now, yes, there are right-wing religious zealots who want to overthrow the American government and replace it with a religious theocracy, and they probably did vote for McCain. And there are anti-capitalist left-wingers who want to destroy free enterprise, and they probably voted Obama. But assuming that you can peek into someone’s head and ascertain their motives just from this is kinda silly. Especially when you yourself had much more rational reasons for whatever vote you cast, right?

The sun was in your eyes, but that other guy is a jerk. Same thing.

My sweetie figmentj and I even talked about this recently. It can be very difficult to separate what a person does from what that person is even when that person is a close friend or a lover, and failing to do so can certainly add to unnecessary pain. “You don’t call me because you are indifferent to me” is very different from “you don’t call me because you don’t like talking on the phone,” and the former is much more hurtful than the latter. While it’s true that a person’s priorities are often reflected in their behavior, and it’s also true that a person who doesn’t care about you is in fact unlikely to call, there’s a long leap from that to “because you didn’t call, you don’t care.” (In fact, the train of thought that goes “A person who doesn’t care about me won’t call me; you are a person who doesn’t call me; ergo, you don’t care about me” is a problem in its own right, because it commits the fallacy of affirming the consequent. Devilishly slippery, this stuff is.)

And it presents itself in other ways, too. “My lover just checked out that hottie who walked into the store. That means my lover is a faithless bastard who doesn’t really love me!” The stories we tell sometimes say more about our own internal fears and insecurities than about the person we’re telling them about.

So, yeah. It’s about what people do, not about what people are. And if you want to change what people do, the best way to do this is to keep the conversation away from what they are.

I have always had a very…special relationship with the Watchmen story.

I was first introduced to the story by Tracey Summerall, a woman who at the time was attending college in Sarasota, Florida. She also introduced me to the Terry Gilliam movie Brazil, among other cult classics, so as you might imagine this had a significant effect on my grasp of pop culture. (In fact, she had a map of the world up on the wall with the Watchmen comics carefully pinned against it, one issue directly over the country of Brazil, a juxtaposition that was not accidental.)

Tracey was my first crush, a fact which eventually led to the demise of our friendship. At that point, I was still young enough I hadn’t yet learned some of the most basic and obvious but nevertheless still not easy tools of interpersonal relationships, among them “more communication is better than less communication,” “if you don’t ask for what you want you can not reasonably expect to have what you want,” and “other people are not responsible for your unvoiced expectations.” In fact, my friendship with her was in many ways instrumental to my learning these things, and she is among the ten or so people who have most influenced the person I later became, though she never knew that, and those lessons came too late to save our friendship. (Funny how that can happen. As it turns out, I learned more than a decade later that she went into exactly the same line of work I went into–when she won a prominent design award in the industry. But I digress.)

Tracey was my first crush, a fact which eventually led to the demise of our friendship. At that point, I was still young enough I hadn’t yet learned some of the most basic and obvious but nevertheless still not easy tools of interpersonal relationships, among them “more communication is better than less communication,” “if you don’t ask for what you want you can not reasonably expect to have what you want,” and “other people are not responsible for your unvoiced expectations.” In fact, my friendship with her was in many ways instrumental to my learning these things, and she is among the ten or so people who have most influenced the person I later became, though she never knew that, and those lessons came too late to save our friendship. (Funny how that can happen. As it turns out, I learned more than a decade later that she went into exactly the same line of work I went into–when she won a prominent design award in the industry. But I digress.)

Anyway, she introduced me to Watchmen, which at the time I thought was the most brilliant and amazing thing I’d ever seen. It wasn’t finished yet; only six of the twelve episodes that made up the full story had been published, and the rest were delayed by nearly two years.

At the time, I lived in Ft. Myers, an hour and a half drive from Sarasota, and the only place in southwest Florida that carried Watchmen was in Sarasota. And they refused to say over the phone whether or not the next issues were available yet. So I’d get in my car each month and make the drive, and as often as not the next part was delayed by something or other and wouldn’t be there. It took, all in all, about a year and change for me to be able to read the whole story.

I still have the first edition, first printing comic book version of Watchmen. Not exactly in pristine shape, but that’s not really the point; I’m neither a collector nor a fan of comic books (and to this day Watchmen is one of only three graphic novels I’ve ever read).

So it’s fair to say that I went into the movie with some high expectations. Watchmen is rooted in a significant part of my personal history, and I have some attachments to it that no movie could reasonably ever be expected to live up to.

I’ve seen the movie twice now. The first time, I went to see it by myself; I gathered up all of my expectations and hopes and bittersweet memories and dragged them all down to the theater with me to see if what was up on the screen could do justice to my past.

When I got home, I posted on Twitter, “Back from Watchmen. Haven’t read it in years. I’d forgotten how brutal it was. Movie is good, but not brilliant.” and went to bed.

Before I went to see it, I didn’t read any of the critical reviews or commentary about the movie, and that was deliberate. Since then, of course, I’ve read a lot of reviews and endless commentary about the movie; Watchmen is, if nothing else, the most talked-about film to come along in a long time.

Before I went to see it, I didn’t read any of the critical reviews or commentary about the movie, and that was deliberate. Since then, of course, I’ve read a lot of reviews and endless commentary about the movie; Watchmen is, if nothing else, the most talked-about film to come along in a long time.

Some of that commentary makes sense, even if I don’t happen to agree with it. Some of it makes me shake my head and say “What?”

There’s a lot of that going around. To be fair, the movie studio didn’t really seem to have a grasp of what they were dealing with; according to several “behind the scenes” and “making of” articles I’ve read, what they wanted was a two-hour, PG-rated movie that could be the start of a whole new franchise.

What they ended up with, of course, is a sprawling, self-contained three-hour movie that barely avoided an NC-17 rating.

And really, it couldn’t be any other way. Seriously. What were they thinking? Any executive who thought Watchmen could be the next X-Men franchise clearly didn’t understand the story. Watchmen isn’t really a superhero story; it’s a brutal, ugly, and morally gray morality play, filled with characters who are at best deeply flawed and at worst are morally reprehensible. The main character is a sociopath, for God’s sake! In one of the film’s more graphic scenes, one superhero beats and attempts to rape another superhero. (Actor Jeffrey Morgan, who plays the superhero The Comedian, describes that particular scene as “three of the hardest days of filming I have ever had to do.”)

What did they think, that they’d be able to release Watchmen Origins: Rorschach a few years from now? What we learn about Rorschach’s past in Watchmen is exactly enough, kthx; anything more would be trawling through a sewer in a glass-bottom boat. The studio should be content with the merchandising tie-ins they’ve already done (“the Comedian deluxe collector figure comes with accessories and multiple guns,” the better to shoot pregnant women with) and be done with it.

One of the complaints I’ve heard that makes sense is about the soundtrack. That complaint I have to agree with; the soundtrack for the film is jarring and in some places incongruous. I understand why the choices were made; I understand what the intent was; I understand that part of the goal of the soundtrack was to ground the film in a particular time, and more importantly, in a particular psychological environment. The choices that were made are logical, but I think were wrong; the audience members who are familiar with these songs are going to bring their own associations to them, and they may not be the associations that were intended. (That was definitely true in several cases for me.)

One of the complaints I’ve heard that doesn’t make sense is that the pacing of the film was wrong.

Watchmen is not a superhero movie. It is a deconstruction of superhero movies. It is a reaction against the comics of the 60s and 70s, that were forced by industry standards to conform to the Comics Code Authority‘s inane Comic Book Code, which required, among other things, that in all comic books “If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity,” “Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates a desire for emulation,” and perhaps most stupidly, “In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.”

Watchmen is not a superhero movie. It is a deconstruction of superhero movies. It is a reaction against the comics of the 60s and 70s, that were forced by industry standards to conform to the Comics Code Authority‘s inane Comic Book Code, which required, among other things, that in all comic books “If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity,” “Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates a desire for emulation,” and perhaps most stupidly, “In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.”

The superhero movies we’re familiar with–X-Men, Spider-Man, Batman–are all based on stories that are products of this code. The code has shaped what we expect from a superhero movie, and I don’t mean just in ways like “superheros don’t commit rape” and “superheros don’t shoot pregnant women.” We expect a certain style of storytelling, with epic battles and chases and exciting music. We expect noble deeds, good, evil, tension, climax, resolution.

That isn’t what Watchmen offers.

What Watchmen offers is the notion that our expectations are stupid, uninformed, and fucked-up from the start. What Watchmen offers is the observation that putting on a mask and beating up bad guys is a pretty fucked-up thing to do, and the fucked-up people who do this fucked-up thing are not likely to be noble in character. What Watchmen offers is the idea that life isn’t neatly divided along lines of good and evil; people are people, and often they’re fucked-up, and people do stuff–some of which is noble and some of which descends to atrocity.

What Watchmen offers is the notion that our expectations are stupid, uninformed, and fucked-up from the start. What Watchmen offers is the observation that putting on a mask and beating up bad guys is a pretty fucked-up thing to do, and the fucked-up people who do this fucked-up thing are not likely to be noble in character. What Watchmen offers is the idea that life isn’t neatly divided along lines of good and evil; people are people, and often they’re fucked-up, and people do stuff–some of which is noble and some of which descends to atrocity.

And sometimes some of the stuff that people do is both at the same time, and sometimes it’s neither, and sometimes people just plain don’t give a fuck, and if that makes you uncomfortable, then that’s too bad. Against the backdrop of war and civil unrest and the possibility of nuclear annihilation, sometimes it really doesn’t matter whether you’re beating up purse snatchers; it’s all just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

For people who walk into Watchmen expecting a superhero flick, there’s likely to be some grumbling. It’s not, even though it’s filled with folks in masks who beat up bad guys. Better, I think, to walk in expecting a mystery. We know how to deal with mystery movies; we expect a slower, more measured pace. We’re not looking for chase scenes and things blowing up. Though even that isn’t quite right; Watchmen starts out with a straight-ahead murder mystery, but in this story, context and subtext are everything.

And how, exactly, do we cope with the superhero who sees all of humanity as a kind of extended lifeboat dilemma and makes the obvious, logical, necessary, and thoroughly evil choice? The story dares us: Are your moral values as resolute as Rorschach’s, the sociopath who has nothing but contempt for human life yet is willing to die for the things he believes to be morally right? “No. Not even in the face of Armageddon. Never compromise,” he says. Would you? Or would you choose to become complicit in atrocity?

One of the reviews of Watchmen I’ve read refers to one of the characters as a “supervillain,” but is he? I don’t believe that he is, and more to the point, by labeling him as a supervillain I think the reviewer missed the entire point of the morality play. One of the unintended side-effects of the Comic Book Code is that it has left pop culture littered with superheros who are incapable of making complex moral decisions, because they’ve never had to.

One thing I felt as I was watching the movie was a sense of disconnect from the emotional impact of the story. When I read the comic-book version, I recall feeling profoundly affected by it on an emotional level, and the emotional response I had to the story became so tangled up in the emotional landscape of all the things going on in my life at that time that now, more than twenty years later, they’re still difficult for me to unpack from each other.

The movie, which in many ways was faithful to the comic to the point of obsession, felt detached to me. The set design, the direction, the costumes, the settings, were all pitch-perfect, but somehow the movie lacked the immediate emotional resonance of the book for me. That might be in part because of my own familiarity with the story, or because the story belongs to a part of my life that is so distant that the person I was then is almost alien and incomprehensible to the person I am now, or because there’s just no way any re-interpretation of the story could ever match the impact of my first exposure to it. I’ve talked to people who didn’t read it first, and they don’t seem to find the movie as flat as I do, so I don’t know.

It is interesting to me how the limbic system can remain static for decades. In almost every way that’s relevant, I am not even remotely related to the person I was in 1986, to the point where I have trouble even understanding the person I used to be, yet the emotional reality of that person is still as clear and present as if it had happened yesterday. This sort of lizard-brain stickiness contributes, I think, to a great deal of human misery; we remember the emotions surrounding things long after the things themselves have faded, and as a result our recollections of people who have been important to us are stained by those emotions and become frozen like flies in amber. We remember arguments that passed a decade ago as clearly as if the door was still slamming, long after we have forgotten the things that drew us to the people around us in the first place. But again, I digress.

Watchmen is not a story that meets with the Comics Code Authority’s approval. It’s brooding and dark and morally gray, and the end of the story leaves the audience stranded in a moral quagmire with no way out. This is not your father’s tale of heros and villains. “In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds”? In Watchmen, we’re left not really sure who is good and who is evil, if indeed those terms are even meaningful at all.

Watchmen is not a story that meets with the Comics Code Authority’s approval. It’s brooding and dark and morally gray, and the end of the story leaves the audience stranded in a moral quagmire with no way out. This is not your father’s tale of heros and villains. “In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds”? In Watchmen, we’re left not really sure who is good and who is evil, if indeed those terms are even meaningful at all.

Watching a conventional superhero movie like Spider-Man or X-Men in the theater is a very different experience than seeing Watchmen; with movies like X-Men, you eat popcorn and the folks around you cheer and you leave the movie feeling excited and happy. There are moments of that in Watchmen, to be sure (both times I saw it, the audience cheered at Rorschach’s “None of you understand. I’m not locked up in here with you; you’re locked up in here with me!”) but Watchmen is the only movie involving superheroes I’ve ever seen where the audience reaction to the story’s final, climactic confrontation is stunned silence (or, the first time I saw it, someone crying). Complicity in atrocity comes easily, and the movie makes us complicit and then twists the knife.

That last confrontation did keep its emotional impact for me. In the end, the technical changes that were made to the storyline, the condensation of the background material, all that stuff doesn’t really matter, though I’m sure hard-core comic geeks will keep using these things in online dicksizing contests for generations to come.

What matters is that the movie achieved the objective of the comic. And in that, I’m by no small measure impressed. Is it a brilliant movie? No, it’s not; but it’s a brilliant story. And that’s what counts.

My birthday is coming up soon. I mention this for two reasons: first, because it means that I have to renew my vehicle registration; and second, because… well, I’ll get to that in a minute.

The registration is relevant to the object of my lust, because, you see, Georgia requires vehicle emissions testing every time the registration on a car or truck is renewed.

This afternoon, during my lunch break, I went to have my emissions tested. The place where this is done is a tiny steel building, about the size of a Quonset hut or metal shed, with a diminutive office–really, a space hardly big enough for two chairs and a magazine stand–attached.

In the magazine stand were several copies of some “high fashion” magazine or other; I don’t remember their names, as they all look the same to me.

In the magazine I picked up at random and flipped through while the technician revved my engine and prodded my car was an article on wristwatches. And in that article was a description of the thing to which I am by degrees coming.

It is a wristwatch made by a company called Romaine Jerome.

It is not a wristwatch in any conventional sense of the term, however. Rather than a dial and hands, it tells time by means of small drums which rotate, and on which are printed numbers. The drums are driven by–get this–a tiny chain, like a bicycle chain whose miniscule links are well under half a millimeter in size. The whole thing is steampunk and retro and gorgeous beyond belief.

This, gentle readers, is the Romaine Jerome Cabestan watch:

Just the thing for a steampunk ‘con costume.

The only down side? Suggested retail price: $220,000.00 US. Did I mention my birthday is coming up?

Frank Miller’s Charlie Brown: A Charlie Brown comic strip as it might be drawn by Frank Miller, the comic book artist responsible for Sin City and The Dark Night Returns.

“That’s right, thumbsucker. I see you…”

Words fail.

I just got my first email spam from a sex toy company located in Pakistan.

Pakistan.

Now let’s think about that for a moment. Pakistan, a deeply Muslim country currently engaging in a low-level civil war with the Taliban, which is arguably the single most repressive religious entity the world has ever seen. And a company in Pakistan is offering to sell me, wholesale, stainless steel knockoffs of NJoy sex toys.

Anyone want to start a betting pool about how long before the guy (and I guarantee it is a guy; women are barely able to leave the house in much of Pakistan) who owns this company is assassinated?

There’s something a little surreal about the notion of a sex toy company in Pakistan.

Once again my Web browser is devouring half of my system’s available RAM and more swap space than you can shake a stick at, so it’s time once again for a long list of links.

Including naturally enough, some Watchmen-related links.

I’ve got several real posts brewing, none of which I’ve actually had time to write (just got home from the office, if that’s any indication), so without further ado, here we go!

Science

Obama to lift restrictions on stem-cell research

Obama Science Memo Goes Beyond Stem Cells

If Obama accomplishes absolutely nothing else in his entire term in office, if he does nothing to stop the pointless and expensive war in Iraq or right the capsizing economy, then his presidency will still be an epic win. Abandoning religious ideology in favor of actual, genuine science is one of the most important things this nation can do. First World superpowers keep their position only by dint of their technological and scientific basis, yet in the past eight years under anti-intellectual Republican rule, the US slipped to #22 in the world in terms of financial support for basic scientific research.

Rewiring the Brain: Inside the New Science of Neuroengineering

This is an incredibly exciting time to live in. We’re closing in on being able to understand and manipulate the stuff of the universe on the smallest scale possible, and we’re also closing in on the ability to understand in ways never before possible the most fundamental things that make us who we are. These areas of exploration bring incredible promise.

New Scientist: Humans may be primed to believe in creation

I’ve written before about how the brain is not an organ of thought so much as an organ for generating beliefs–a “belief engine,” if you will–and this research shows that a predisposition belief in purpose is a very strong component of that belief engine.

Missing Link Between Fructose, Insulin Resistance Found

For the first time, a concrete, documented mechanism between fructose and fructose-containing sweeteners and diabetes is uncovered.

Sociology

The Vatican uses the line “life must always be protected” to justify the excommunication, in apparent ignorance of the irony that without the abortion, the young rape victim, and the babies, would have died.

Bush: ‘Sanctity of Human Life Day’

In the last days of his Administration, former President Bush declared Jan. 18 to be “National Sanctity of Human Life Day.” Apparently, the sanctity of human life doesn’t apply to the citizens of Middle Eastern nations that happen to be geographically close to other nations that were responsible for terrorist attacks on us.

Steve Pavlina: 2009 Focus – Intimate Relationships

So there’s this guy who is…well, I’m not exactly sure what he is. He seems to be a motivational coach (or “personal development” coach, whatever that is). Anyway, he writes a blog, and in his blog he says that 2009 is the year he’s going to explore polyamory. And he linked to my site on his list of resources.

Bizarre

Photos of abandoned Russian ships frozen in ice

I really, really, really, really want to visit this place. The Russians have always been amazing at taking urban decay to the next level, and this place is just beautiful.

The Most Amazing Star Trek Collectible of All Time

If by “amazing” you mean “horrifying beyond all human reason.” The commentary is priceless.

Watchmen condoms: We’re society’s only protection

If you want your schlong to look just like Dr. Manhattan’s, now’s your chance! These blue condoms come in a flip-top case with the smiley face on the front, and …yeah. I have nothing else to add.