Okay, so. Let’s talk about cancel culture.

Cancel culture isn’t what a lot of folks think it is.

You can’t reasonably address the notion of what “cancel culture” is until you first address what it isn’t. Cancel culture is not saying “I don’t like the way that company does business, so I’m not going to shop there.” Cancel culture isn’t “I don’t like what that person did, so I’m not going to watch her movies.” Cancel culture isn’t even “I don’t like what that company or that person did, so I’m going to tell others how I feel about them.”

All those things are simply you making your own choices. No company is entitled to your money; you’re not taking something away from a corporation that rightfully deserves it by not shopping there. No movie star is entitled to you seeing their movies. No TV comedian is entitled to have you watch their shows. No author is entitled to have you read their books.

Cancel culture, if we are to be intellectually honest, is something else. Cancel culture is the idea that someone or some company did (or you think they did) something wrong, so you aren’t going to patronize them, and you are going to try to force other people not to patronize them either.

Probably the classic example of cancel culture in United States history was McCarthyism, where the government used political witch hunts to force people out of their livelihoods because someone said their brother overheard their hairdresser telling someone else they might be Communist.

Anyone who stood by someone accused of Communism was also branded a Communist. Anyone who defended someone accused of Communism was also driven out of their jobs. Anyone who stood up and said “hey, wait a minute…” was branded a traitor and publicly hounded.

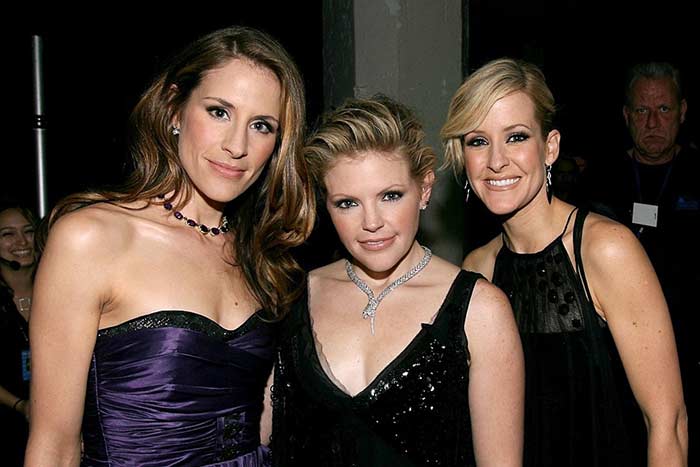

The most dramatic recent example of cancel culture was probably what happened to the Dixie Chicks, who incited the wrath of right-wingers by criticizing the Iraq war.

Many people stopped buying their albums. That’s not cancel culture.

However, they also demanded radio stations stop playing their music. They stalked and harassed managers of radio stations that played their music. They sent death threats to radio DJs who played their music. They phoned firebomb threats to venues that hosted their concerts.

That’s cancel culture.

Cancel culture is not “I will not patronize this person.” Cancel culture is “I will make sure nobody else patronizes this person.”

There are a lot of moving parts to cancel culture; while it predates the Internet (and possibly human civilization), the Internet has made it a flash phenomenon, able to incite enormous fury at the slightest breath.

And while in the past it has frequently been dominated by the political right—I laugh every time an American conservative accuses liberals of “cancel culture,” given the Dixie Chicks thing and the Starbucks thing, cancel culture is neither a left thing nor a right thing. Folks of all political persuasions do it.

Some of the key elements of cancel culture include:

Mass outrage. “Look what they have done! They have criticized our President/sold us out to Commies/said a bad thing/whatever! Outrage!!!” Often, the outrage comes with scanty supporting evidence, and frequently it’s presented with the most emotionally laden spin possible.

Appeal to popular narratives. Narratives are powerful. Human beings are a storytelling species; we understand the world through stories. The stories we tell ourselves—”the government is bad and trying to harm me,” “men are abusers; women are victims,” “nothing an opposing politician says is ever true,” “gay men are pedophiles”—shape our understanding and perception of the world. Stories we hear that fit our narratives tend to be believed without question. Stories that contradict our narratives tend to be rejected without consideration.

These two things often work in synergy. Something that contradicts or violates a narrative we accept will often generate a disproportionate emotional response…not only because it introduces cognitive dissonance, but also because these narratives are:

Tribal markers. The narratives we accept become the way we tell in-groups from out-groups. They are, in a literal sense, virtue signaling and identity politics; the people who believe the same narratives are ‘us,’ while those who reject our narratives are ‘them.’

A clearly defined Good Guy, clearly defined Bad Guy, and clearly defined crime—often, a crime against whatever values once made the Bad Guy a Good Guy. In the political right, this tends to be defiance of authority figures the Right accepts (President Bush, Donald Trump); in the political left, this tends to be perception of or accusation of sexual or social impropriety.

This is why the US left and US right accuse one another of “cancel culture” but don’t see what they themselves do as “cancel culture.” We didn’t cancel the Dixie Chicks; we responded to their unacceptable disrespect of our President! We didn’t cancel that comedian; we responded to defend disadvantaged groups from his attack!

Targeting not only of the person being canceled, but anyone nearby. Cancel culture is, by its nature, an attempt to coerce everyone into shunning the person or entity being canceled. The best way to do this? Target anyone who stands by that person or entity. Doing this sends a clear and unmistakeable message: Defend the person we are canceling and we will ruin you, too. People like to think of themselves as upstanding moral entities who will do the right thing under pressure. Threaten someone’s livelihood or reputation and I guarantee, guarantee, the overwhelming majority of those who think of themselves as good, stand-up people will fold like wet cardboard. There’s no percentage in having your own reputation ruined and your own livelihood destroyed for the sake of someone else.

Intolerance of dissent. This same targeting happens to people who say “hold up a second, are you really sure this is what you say it is? Are you certain this person did what you think they did? Should we hear from this person?” Reminding someone in the throes of a full-fledged righteous wrath that stories have more than one side invites you to be cast out, set on fire, and nuked from orbit.

Rejection of nuance. Cancel culture thrives on self-righteousness. The people who engage in canceling truly, absolutely, 100% believe they are truly, absolutely 100% right. They truly believe they are on the side of the angels, casting out unutterable darkness itself. The idea that there might be anything other than a purely good side and a purely evil side lets the air out of that self-righteousness, and that invites in feelings of shame and guilt.

The trouble with all of this is it allows for no self-reflection and once started, cannot be recalled. The people who phoned bomb threats to Dixie Chicks venues continue, to this very day, to believe that what they did was right…because once you’ve taken that step, how can you sleep at night if you tell yourself ‘no, actually, I was over the top, I shouldn’t have done that’? Once you’ve accused something of some wrongdoing, even if on some level you know it isn’t true, you can’t take it back without the risk of that same outrage machine turning on you; you have to keep going.

In 1937, Winston Churchill wrote:

Dictators ride to and fro upon tigers from which they dare not dismount.

He was talking about populism, but where populism is the politics of human tribalism writ large, cancel culture is the politics of human tribalism writ small, and the same idea applies. When you’ve saddled up that tiger, you don’t dare dismount lest it stop eating your enemies and eat you instead.

So what does this have to do with political correctness?

“Politically correct” is a fudge phrase. It’s like “respect” that way.

In 2015, a Tumblr user on a now-deleted blog wrote

Sometimes people use “respect” to mean “treating someone like a person” and sometimes they use “respect” to mean “treating someone like an authority”

and sometimes people who are used to being treated like an authority say “if you won’t respect me I won’t respect you” and they mean “if you won’t treat me like an authority I won’t treat you like a person”

So when you hear the word “respect” in a political conversation, that should raise the small hairs on the back of your neck. Odds are good someone’s about to pull a lingusitic switcheroo on you, and if you don’t pay attention, you’re gonna get snookered.

Sometimes people use “politically correct” to mean “treating other people with decency and compassion” and sometimes people use “politically correct” to mean “adhering to a rigid dogmatic orthodoxy.”

And sometimes people will go into a conversation using it the first way, and when you agree you think that’s a fine idea, they’ll point at you and say “See! You’re just trotting out your identity-politics dogmatism!”

And then whatever idea you’d been advocating gets dismissed as empty virtue signaling.

It’s easy, oh so very easy, to pick up the torch and the pitchfork when you hear something that presses your emotional buttons. And yes, you do have buttons, and so do I, and so does everyone.

Outrage is the enemy of reason. It’s easy to get swept up in the righteous fury of outrage. I’ve done it. I struggle to name anyone who hasn’t. That outrage makes you a tool, a weapon in someone else’s hands…and sickeningly often, if you scratch the surface of justifiable moral outrage over some clear and obvious moral wrongdoing, you’ll find something cheap and tawdry beneath.

Something like money. Or influence. Or political power.

The irony is that political correctness of the first sort—compassion, empathy, a sincere desire to see things from many perspectives, a rejection of the easy and convenient narrative—is actually the antidote to cancel culture, which rests on a foundation of political correctness of the second sort.

But political correctness of the second sort feels better. Picking up the torch and the pitchfork feels good. You feel like you’re in the right. You feel like a superhero. You feel like you’re riding into battle against evil itself. And best of all, you can do it easily, from home, without risking anything!

Funny thing about that. If what you’re doing makes you feel heroic without risking anything…maybe it’s not as heroic as you think it is.

I disagree with the thesis that:

> Cancel culture is the idea that someone or some company did (or you think they did) something wrong, so you aren’t going to patronize them, and you are going to try to force other people not to patronize them either.

Specifically because of the word “force.”

Shame people into doing it? Sure. Scream at the top of your lungs about it? Of course. But cancel culture famously lives on the internet, and it’s pretty difficult to force someone to do something over twitter.