…I have nearly $90 in credit at Amazon.com.

*runs off to buy a great big pile of books*

…I have nearly $90 in credit at Amazon.com.

*runs off to buy a great big pile of books*

One of the (few) panels I actually managed to drag myself to at Dragon*Con was a panel on the Cassini space probe currently poking around Saturn. The panel was hosted by Trina Ray, who works as Science System Engineer for the Cassini program at NASA–which is a pretty damn cool job to have, if you ask me.

In all fairness, it wasn’t the panel I had wanted to see. The panel I’d intended to see, whose name I don’t even remember now, was full; the Cassini panel was next door, and relatively empty, and my feet hurt. So in we went.

It turned out to be one of the best panels of the con.

The Cassini mission was originally intended to explore Saturn and one of its moons, Titan. Along the way, it’s discovered some strange and interesting things, particularly with regards to another of Saturn’s moons, Enceladus.

Now, Enceladus doesn’t really seem, at first glance, like a terribly interesting body. It’s basically a ball of ice about the size of Arizona; cold, distant, orbiting around Saturn like…well, like a big lump of frozen water.

Ah, but the universe is a vast and surprising place, full of weirdnesses too countless to apprehend.

Cassini has, among other things, instruments capable of analyzing and determining the chemical makeup of the matter around it. When it comes to pass that those instruments, while the ship is passing near a giant ball of ice, suddenly register a great deal of water, and then just as suddenly register bupkis, one parsimonious explanation is that the instruments are on the fritz. Another explanation is that there’s a massive honking big jet of water spewing for hundreds of miles out of the big lump of frozen water, but that doesn’t make any sense, does it? Big, cold lumps of frozen water aren’t usually in the habit of spewing out gigantic jets of liquid water, much to the relief of folks who own freezers everywhere.

Now, if there is a big jet of water spewing out of a ball of ice, it’s the sort of thing you’d expect to be able to see, particularly if you arrange to look for it when it’s backlit by the sun. Some rejiggering of orbital mechanics and other rocket-science stuff later, the Cassini was able to take a picture in just that sort of situation, and here’s what it saw:

Lookit that! A big honking jet of water.

Now, this isn’t the sort of thing you’d expect if you were talking about a ball of ice orbiting a distant gas giant. Enceladus is cold. It’s bright white, so it reflects most of what little sun is available from so far away. In fact, it’s actually, for the most part, the coldest object in orbit around Saturn, with surface temperatures near the equator of around -315 degrees Fahrenheit.

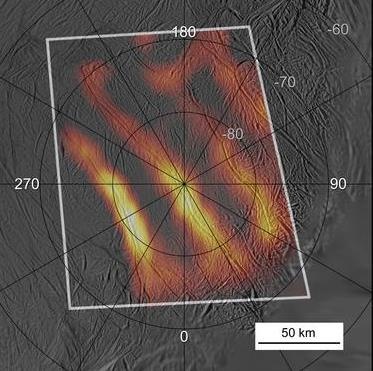

And yet, it’s spewing out jets of liquid water. Which is weird. It’s also hot at the poles. Which is weirder. And the heat is concentrated in weird stripes at the south pole, which is weirder still:

So what we’ve got here, basically, is a ball of ice that’s not really a ball of ice at all. It’s being heated by some internal process, it’s spewing out jets of water through fissures in the icy surface, these jets of water have all migrated (or possibly rotated the entire moon) so they’re exactly at the south pole, and…

Oh, wait, I forgot to mention something. It’s not just water. It’s also got organic molecules of various sorts in it.

What we’re left with, then, is a moon that’s got a crust of frozen water with a liquid core of molten water, in much the same way that the earth has a crust of solid rock with a liquid core of molten rock. The water within the moon spews out in huge plumes via a process called “cryovolcanism”–and how cool is that word, by the way? Cryovolcanism. The moon’s south pole is covered with cryovolcanoes.

And they spew out a lot of water. In fact, it looks like the largest ring around Saturn, the E-ring, is created by Enceladus. The ring is a vast structure of little tiny ice crystals, which come from these cryovolcanos on the moon’s surface.

Now, let’s sit back and think about this for a bit.

We have heat. We have liquid water. We have organic molecules. We have, in Ms. Ray’s words, a compelling reason not to ditch the Cassini, when it reaches the end of its life, on Enceladus.

Because, you see, those are the basic ingredients necessary for life–heat, water, organic molecules.

Now, if you look at most conventional science fiction, you see that a great deal of it is concerned with life in outer space–something which has never been demonstrated, but which nevertheless seems rather likely. And much of the bulk of this kind of science fiction concerns itself with life as it might exist in places that are like earth.

Which shows, I think, a failure of imagination.

The human imagination, as I’ve often said, is surprisingly feeble. When given a stunningly vast universe filled with all manner of weirdness, we set our imaginary stories in places that look like Wyoming. When confronted with the breathtaking diversity of biology just here on earth, the best we can come up with is imaginary creatures like Bigfoot–half man, half ape, all lame. When we ask ourselves how such a marvelous, beautiful place as the universe could come to be, the best we come up with is a bearded old guy who created the earth (whose surface is seventy-five percent water) exclusively for man (who has no gills), and since that epochal moment of creation has largely confined himself to a near obsession with women’s clothing and the occasional vaguely Mary-shaped swirl in somebody’s French toast.

I came away from the panel impressed all over again with the majesty and incredible, mind-boggling wonder and beauty of the physical universe. This stuff is so incredible, so fantastical, so amazingly bizarre and splendid that it’s hard to understand how anyone, confronted with this, could not be awed by the complexity and surprises the universe has to offer.

After it was over, Shelly turned to me and said “How come more people know about Britney Spears’ sister than know about this?” And you know, I don’t have an answer.