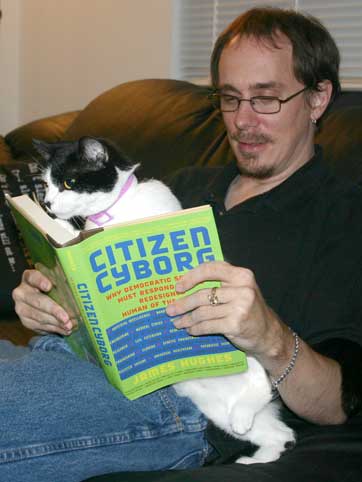

I finally got my own copy of James Huges’ transhumanist book Citizen Cyborg, after flipping through smoocherie‘s copy some time ago. It actually arrived last week, just as Shelly and I were preparing to drive out to Ormond Beach to spend the weekend camping with smoocherie and her partner Fritz. It’s one of the tangible benefits of my Web site; I maintain a list of books and resources about polyamory and another similar list of resources about BDSM, and every year enough people visit my resource pages and buy books from it that I can afford to get two or three books myself from Amazon.

I just recently had a chance to settle down and start reading it, which I need to do soon as we’re scheduled to have dinner with James Huges, the author, the first week in January.

I wrote some time ago about how my kitty Snow Crash is not an Extropian, and why this was bad for society. The same cannot be said of Molly, the other kitty, who is an extropian of the highest order. No sooner had I settled in and begun reading than she was all over me like white on…er, on public water fountains and in public schools in the segregated South before more reasonable people intervened and said “Listen, I don’t care what your goddamn tradition says, treating people as inferior just because they’re black is wrong.”

The camping trip was great fun. We stayed out in Ormond Beach for a couple of days, talking philosophy and kayaking and watching Invader Zim on Cherie’s laptop and gathering around the campfire for lesbian orgies. (Campfire + toasted marshmallows + chocolate + graham crackers + Shelly + smoocherie = lesbian orgy, but I digress.)

I’ve actually become quite spoiled. I’ve seen quite a lot of smoocherie lately; it’s almost enough to make me forget that it is, technically, a long-distance relationship. She and Fritz spent last weekend with us, and it’s been so jam-packed with industrial poly goodness I’ve scarcely had time to catch my breath.

Friday: What’s outside? retailiation what’s outside? burning flags what’s outside? the pressure of daily life what’s outside? nothing to be afraid of we believe in we believe in the future of the human race

Front 242 played in town on Friday. The four of us joined nihilus, datan0de, nekidsteve, and alias_node–who’d gone off his pain meds to be there–for an evening of industrial/EBM goodness at 130 beats per minute. great show, but the real pleasant surprise was the opening act, Gray Area. I know nothing about these guys and hadn’t even heard of them, but wow, they’re really, really, really good.

alias_node got clipped pretty hard in the back during the show and was in a great deal of pain, complaining that his vision was all funny, so he went to the after-show party at the Castle and the rest of us went out for ice cream and headed home. If there were two words to describe alias_node and they weren’t “deleriously happy,” the first would be “hard” and the second would be “core.”

Saturday: What the flame does not consume, consumes the flame.

smoocherie had been invited to the Southern Polyamory Gathering, which I’d never heard of. She, Fritz, and I piled into her Prius, sans Shelly, who had far too much homework to do but gave us quite the cute sendoff anyway:

She’s such a cutie…but I digress. Anyway, the three of us scoped out the pagan poly folks for a while, then crushed them all in our iron fist inadvertently ended up dominating the talk circle with matters of practical, hands-on polyamory.

Neat bunch of people, for the most part, though many of them seemed remarkably unaware of the Internet, which probably accounts for the fact that there’s near-zero crossover between the local pagan poly community and the rest of the poly community at large.

I’m always surprised when I encounter some counterculture group that doesn’t make use of the Internet. How do they find each other?

In the foreword of Citizen Cyborg, James Huges talks about “bioLuddites”–people resistant to technological change in general and change in biomedical technology that threatens to make us re-examine our ideas abouut what it means to be human and what it means to be a person in particular. What’s interesting about these people is they come from all over; they’re a mix of far-right religious Fundamentalists, social conservatives, environmental activists, far-left anti-capitalist and anti-consumerist advocates… you name it. I catch a faint whiff of resentment to technology and to transhumanist ideals in much of the pagan community, which makes the irony of the fact that smoocherie‘s Toyota was the only hybrid among a sea of hulking Ford and GM SUVs all the sharper.

Afterward, Aeon Flux.

I won’t give away any of the movie, though I will say that they did an excellent job of preserving the visual language of the original comic, live-action aside. Charlize Theron was not an intuitive choice for Aeon, though she handled the role magnificently. The story was okay; had some glaring plot holes, and it, too, had an undercurrent of anti-transhumanist ideology. (“Humans were meant to die”? WTF is that all about? But again, I digress.) Pros: More coherent than the cartoon, though that’s not saying much; an epileptic who’s just overdosed on PCP is more coherent than the cartoon. Cons: Not the same characters.

Fritz observed, right on the mark, that the characters of Trevor and Aeon in the cartoon can be seen as archetypes of radical order and radical chaos; each is more or less indifferent to the consequences of their actions on the people around them. The movie redefined the characters radically; Aeon was still more or less recognizable, but Trevor wasn’t even in the same ballpark, or for that matter in the same city, or the same sport, even. in the cartoons, the single overriding factor in his psychological makeup is his boundless, cast-iron arrogance, something completely lacking in the new, redesigned Trevor.

Sunday

I have no clever quotes for Sunday. Sunday was PolyCentral, a once-monthly Orlando meeting of all us polyamorous freaks. Shelly accompanied us, despite the crushing amount of homework piled atop her as she goes into finals; she did homework in the car on the way there, homework at the restaurant, and homework in the car on the way back. PolyC’s current home is a Thai sushi restaurant, whose owners are apparently involved with two other couples in some capacity I’m not entirely clear on, and plan at some point to sit in with the rest of us freaks.

Then back home for studying, sex, and World of Warcraft, more or less in that order.

Tonight, my sweetie S‘s other partner, whose name also begins with the letter S, has invited Shelly and I to Cirque du Soleil. God is an iron; he lives in Orlando, she lives here in Tampa (a very short distance away, in fact), and her schedule has been so over-the-top busy lately that I’ve seen more of him than I have of her in the past couple of weeks. (No, not that way, you perv!)

Bad poly: Resenting your partner’s other partner. Good poly: Going to Cirque do Soleil with your partner’s other partner because she’s busy for the evening.

And now, alas, more work beckons.

Like this:

Like Loading...