Recently, a Quora user asked a question about what problems we, the Internet horde, have with leftists.

I kinda wanted to start my answer with “the biggest problem I have with leftists is how easily they turn to being whiny, self-indulgent, virtue signaling pricks too lazy to do the work demanded by the ethics that they so love to pat themselves on the back about,” but Joreth thinks maybe that might not go over so well as an introductory paragraph, so perhaps I’ll start a bit more gently.

Oh dear. It seems I’ve started that way after all. Well then, to arms! Cry havoc, and let slip the dogs of war! I mean, god knows I spend a lot of time dishing on conservatives, so maybe it’s time for liberals to get some of that attention. You know, in the spirit of generosity and fairness of heart.

Image: stillfx on Adobe

One of the biggest differences between liberals and conservatives centers on social organization, and appears to be a consequence of concrete, identifiable structural differences in the brain.[1][2][3]

Conservatives favor vertical social hierarchies divided into leaders and followers, high status and low status.[4] A place for everyone, in other words, and everyone in their place.

Legitimate authority is to be obeyed without question; questioning authority is treason, an offense against all society. People on the bottom of the hierarchy should know their place and not get uppity.

People are sorted by physiology, and presenting yourself outside the accepted norms that communicate your station and position in the hierarchy—men wearing “women’s” clothing, people of one race “putting on airs” of another race (especially one of higher stature), these things are absolutely unacceptable.

Liberals, on the other hand, favor a horizontal, flat social organization. Leaders are not above everyone else, they serve everyone else. Questioning leaders to keep them on the right track? That’s not treason, that’s Tuesday. People who are structurally marginalized or disempowered by social convention? It’s the duty of society to equalize their position.

Which, okay, well and good, but…

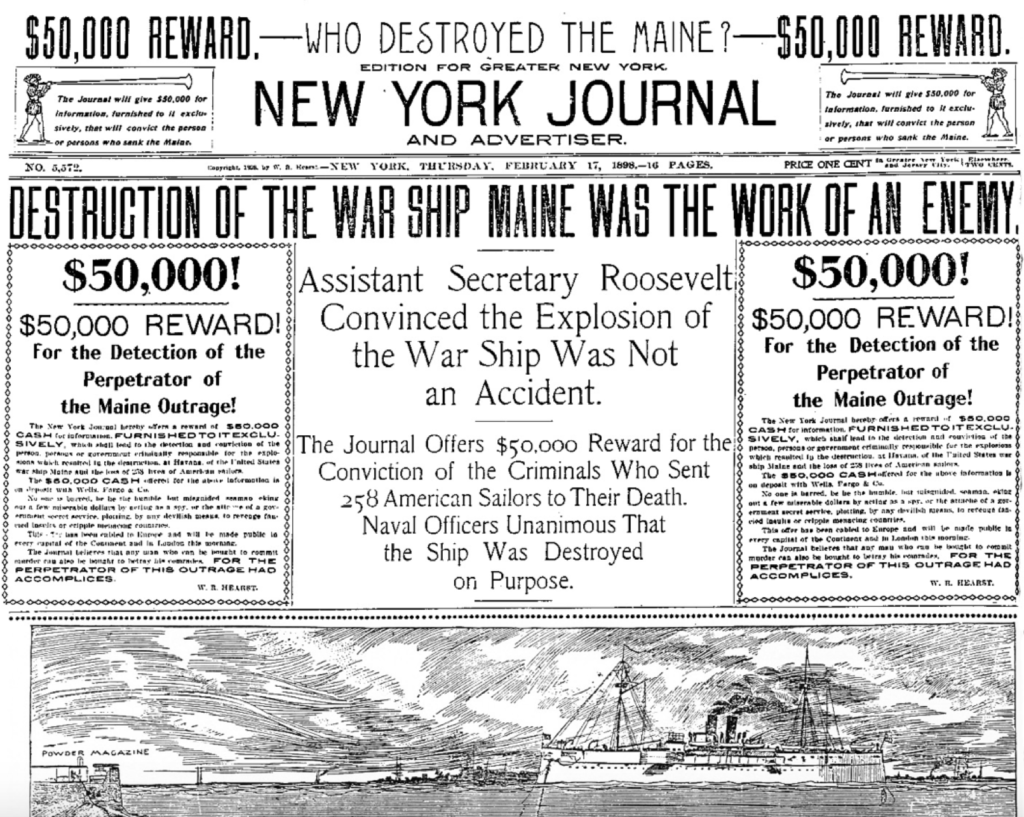

Liberals like to ridicule conservatives as delusional imbeciles with their “alternative facts,” weird conspiracy nutters always yammering on about absurd hallucinations like “Jewish space lasers” and Democrat sex-slave rings run from the basement of a pizza shop that’s doesn’t have a basement.

But at the same time, liberals embrace their own delusions, they’re just delusions of a different flavor, and they go right back to that horizontal social structure ideology.

So a couple years ago, this guy:

got into hot water over the N-word.

No, not that N-word. The Chinese word 那个, pronounced something like “nà ge.”

This guy is Greg Patton. He’s a professor at the University of Southern California, where he teaches, among other things, business communication.

He was teaching about filler words—words that lack specific meaning but are inserted as pauses. English filler words include “like,” “uh,” and “um.” Spanish filler words include “pues” and “a ver.” German filler words include “ach so” and “klar.”

Chinese filler words include 那个. And 那个 sounds enough like the other n-word that students complained and he was removed from the class.[5]

This illustrates a problem, absolutely endemic in certain liberal circles, that several people I know call “rounding up to abuse.” Liberals get absolutely giddy over the idea that one of their own turns out to be An Abuser of some kind—a secret racist, a secret homophobe, whatever. They absolutely delight in it, and so will go hunting for reasons to label people atop the current social hierarchy Bad People.

Why?

Part of it is personal kudos and virtue signaling. “Look at me! Look at me! I’m not like those others! Watch as I tear down the hierarchy! Watch me stick it to The Man! Hey, everyone, look at me! Aren’t I wonderful? I’m a good person! I stand with the downtrodden! Praise me!”

But that’s only part of it.

Part of it is that a lot of liberals absolutely, positively loooooove being bullies…as long as they can make themselves believe their bullying is in defense of the marginalized and downtrodden.

image: Victor on Adobe

Yes, I’m serious.

I know liberals always whine about what bullies conservatives are. “The cruelty is the point,” we say of conservative policies.

And it’s true. Conservatives love bullying. They’re quite open about it. They get off on it. That’s why they punch down; in the hierarchical order of things it’s acceptable to bully people lower on the hierarchy than you are.

Liberals also love to bully people, but they’re sanctimonious about it. They say they don’t, and one of their favorite pastimes is feeling superior to conservatives because conservatives are so gleeful about punching down.

However, when liberals see an opportunity to bully someone and can rationalize it to themselves, they throw themselves into it with a zest and zeal that puts conservatives to shame. Liberals love bullying just as much as conservatives do, it’s just that liberals lie (and lie to themselves) about it.

Liberals are sanctimonious about how awful it is when conservatives punch down. But the truth is, liberals are better bullies than conservatives are…BECAUSE they’re sanctimonious about it. Far too many liberals believe—absolutely, truly believe—that if they can just find the RIGHT people to bully and harass, they can somehow bully and harass their way to a more just, more equitable, more peaceful and harmonious Utopia.

They look for reasons to bully—they round up to abuse, they get outraged because 那个 sounds like the n-word—because a white dude using the n-word is someone they’re allowed to bully, someone they feel good about bullying.

They wanted Greg Patton to be slinging the n-word around in his class, because it gives them license to let slip their inner bully and feel good—no, feel righteous—about it, and score virtue points with their fellow liberals at the same time. Liberals get off on that.

In short: Conservatives bully because it maintains the hierarchy. Liberals bully because it’s fun, and it makes them feel good about themselves.

The fact that Greg Patton didn’t actually use the n-word doesn’t matter. Liberals wanted him to have used it, because it feels so goddamn good to pick up the torches and pitchforks—it’s a big part of how liberals show themselves and each other that they’re Good People on the Right Side of History.

And if Greg Patton is generally fairly progressive himself? So much the better. Now they can show how fair-minded they are—they even go after the baddies in their own ranks! Not like conservatives. Oh no, we hold everyone accountable! See how good we are? Praise us!

Truth doesn’t matter. Reality doesn’t matter. What matters is that desire to prove your worthiness by attacking the bad guy, whether he’s actually a bad guy or not. (Greg Patton was completely exonerated after an investigation[6]—fortunately for him, he’d recorded the class.)

Image: @anniespratt on Unsplash

This is one thing self-described “social justice warriors” consistently get wrong. Truth matters. There can be no justice without truth. If your “social justice” has no truth-finding mechanism, it’s about conformity and mob rule, not justice.

I feel this should be obvious. Why is this not obvious?

Conservatives often accuse liberals of racism and sexism, in a “you want to keep Black voters dependent” and “you want to tell women they aren’t allowed to be mothers and housewives” kind of way.

This is, of course, absolute bullshit, not even remotely true…

…but it is in the neighborhood of truth.

Liberals often think in terms of archetypes. They’ll say on the one hand that we’re all people—young or old, black or white, man or women, we all deserve equal treatment.

Which is true.

But then on the other hand, they’ll tend to see people in terms of archetypes. oppressor and oppressed.

You see this play out in simplistic, bumper-sticker liberal morality. “Believe women” is an example. Not “support people who say they’ve been abused while also fact-checking,” which is too complicated to fit on a bumper sticker and therefore doesn’t work well with liberal virtue signaling.

Let’s turn that around a bit: “Believe whites.” That…feeeeels a little uncomfortable, doesn’t it?

Why is the one okay but the other isn’t?

Liberals will probably tell you “well, as a historically marginalized group, women have long been accustomed to not being believed, so historically, thee’s an imbalance that needs to be rectified, and and and…”

And and all of that is true. But why “believe women” rather than “don’t automatically disbelieve women?”

Because “believe women” lets you virtue signal while also avoiding, you know, actually doing the work that the ethics you claim to have would require.

If you have two different individuals who say two different things, and your goal is truth, you have work to do. It takes effort. It takes investigation, it takes careful consideration, it takes mental and (dare I say it?) emotional labor.

If, on the other hand, your social group tells you that there’s one side you always and automatically believe—you always believe the white person, you always believe the woman—then you can short-cut all that “truth” and “evidence” and “careful, critical thought” stuff to get to the ‘right’ answer—which is, of course, the one that gains you social standing in your social group.

Different classes of people are not treated as individuals by liberals. They’re treated as a member of their class, with built-in assumptions about who is hero and who is villain based on perceptions of which group is the oppressor and which is the oppressed.

That’s why you’ll see questions like this on Quora:

Actual question on Quora

This question is, of course, utter nonsense. We don’t despise Thomas because he’s black, we despise him because he’s corrupt.

And yet, liberals tend, by and large, merely to wave an airy hand and dismiss questions like this, without ever asking: Why would someone ask this? Where would they get this idea from?

Asking that question leads in some uncomfortable directions. Directions like, might someone who watches the behavior of many liberals each the conclusion that liberals hold double standards, condemning a behavior from someone they might justify or even accept from a different person who belongs to a different social group? (Uncomfortable answer: yes. I’ve witnessed liberals with radically different responses to domestic violence by men against women and by women against men.)

We liberals mock double-standards held by conservatives, while ignoring the plank in our own eye. This isn’t a liberal/conservative thing, it’s a human thing—we all, including you, including me, hold double standards—but goddamn, liberals can be so sanctimonious about our own double standards.

Which brings up another difference between conservatives and liberals: Conservatives attack the Other. Liberals attack their own.

There’s nothing more infuriating to a liberal than a fellow liberal who’s 99.87% in agreement with them—that last fraction of a percent is MORAL IMPURITY that must be PURGED WITH FIRE.

All you liberals who bitch and moan that liberal politicians are so ineffective, listen up: you can’t build your new egalitarian Utopia when you’re preoccupied with knifing your friends in the back.

This is the natural consequence of the horizontal vs vertical social hierarchy thing. In vertical hierarchies, those below always accept any behavior from those above.

Like Trump, for example. Those who accept him as rightful leader excuse his grift, his lies, his incessant self-absorbed pandering, his philandering, because he’s at the top of the hierarchy and submission to rightful hierarchy is a core moral value.

Liberals, on the other hand…if you’re not 100% with me, I will cast you into the lake of fire. Deviate even one iota and you’re gone.

This:

is funny because it’s true. It’s absolutely classic leftist behavior, and it’s one of the things that makes leftists so goddamn toxic.

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3092984/

[2] https://neuro.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16030051

[3] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/conservative-and-liberal-brains-might-have-some-real-differences/

[4] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/many-differences-between-liberals-and-conservatives-may-boil-down-to-one-belief/

[5] https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/09/08/professor-suspended-saying-chinese-word-sounds-english-slur

[6] https://www.uscannenbergmedia.com/2020/09/29/usc-concludes-professors-controversial-comments-did-not-violate-policy/

To understand what is happening now, and why the American right doesn’t consider their vilification of the Capitol police hypocritical, I think we need to understand John McClane, the Hero’s Journey, Rugged Individualism, the American monomyth, and authoritarianism. Those are the ingredients that make up that particular toxic brew.

To understand what is happening now, and why the American right doesn’t consider their vilification of the Capitol police hypocritical, I think we need to understand John McClane, the Hero’s Journey, Rugged Individualism, the American monomyth, and authoritarianism. Those are the ingredients that make up that particular toxic brew.