In less than three weeks, the end of the world will happen.

In less than three weeks, the end of the world will happen.

Or, rather, in less than three weeks, a bunch of Mayan-prophesy doomsdayers will wake up and, if they have any grace at all, feel slightly sheepish.

The Mayan epic calendar is set to expire on December 21, or so it seems, and a lot of folks think this will signal the end of the world. They really, truly, sincerely believe it; some of them have even written to NASA with their concerns that a mysterious Planet X will smash into Earth on the designated date. (There seems to be some muddling of New Age thought here, as the existence of this “planet X,” sometimes called Nibiru, is a fixture amongst certain segments of the New Age population, its existence allegedly described in ancient Sumarian texts.)

It’s easy to dismiss these people as gullible crackpots, uneducated and foolish, unable to see how profoundly stupid their fears are. But I’m not so sure it’s that simple.

Apocalyptic fears are a fixture of the human condition. The Mayan doomsday nonsense is not the first such fearful prediction; it’s not even the first one to grab recent public attention. Harold Camping, an Evangelical Christian, predicted the end of the world on October 21, 2011…and also on May 21, 2011, September 7, 1994, and May 21, 1988. He got enough folks worked up about his 2011 predictions that many of his followers sold their belongings and caravanned across the country warning people of the impending Apocalypse.

These kinds of predictions have existed for, as near as I can tell, as long as human beings have had language. Pat Robertson has been in on the action, predicting the Great Tribulation and the coming of Jesus in 2007. These fears are so common that a number of conservative politicians, including Sarah Palin, believe that the current generation is the last one the world will see.

Given how deeply-woven these apocalyptic fears are in the human psyche, it seems to me they speak to something important. I believe that, at least for some people, such fears of impending doomsday actually offer protection against an even deeper fear: the fear of irrelevance.

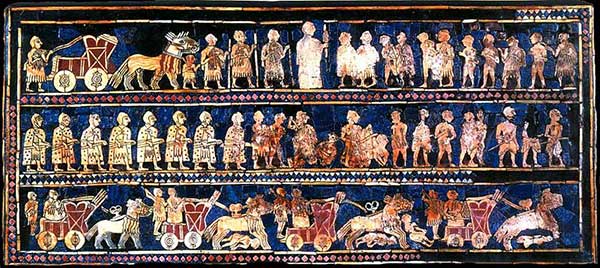

My readership being what it is, I bet the percentage of you who recognize this picture is probably higher than the percentage of the population as a whole who recognize it.

This is part of the Standard of Ur, an artifact recovered from archaeological digs from the site of Ur, one of the world’s oldest cities, in what is now present-day Iraq.

Ur was likely first settled somewhere around 3800 BC, or roughly six thousand years ago, give or take. That puts its earliest settlement at about the start of the Bronze Age, plus or minus a century or so. The Agrarian Revolution was already well-established, but metallurgy was fairly new. When it was built, it was a coastal city; that was so long ago that the land itself has changed, and the ruins of Ur are now well inland.

You’ve probably at least heard of Ur; most public schools mention it in passing in history classes, at least back when I was a schoolkid. Unless you’re a history major, you probably don’t know much about it, and certainly don’t know a whole lot about life there. Unless you’re a history major, you probably don’t think about it a whole lot, either.

Think about that for a minute. Ur was a major center of civilization–arguably, the center of civilization–for centuries. History records it as an independent, powerful city-state in the 26th century BC, more than a thousand years after it was founded. People were born, lived, loved, struggled, rejoiced, plotted, schemed, invented, wrote, sang, prayed, fished, labored, experienced triumph and heartbreak, and died there for longer than many modern countries have even existed, and you and I, for the most part, don’t care. Most of us know more about Luke Skywalker than any of the past rulers of Ur, and that’s okay with us. We have only the vaguest of ideas that this place kinda existed at some vague point a long time ago, even though it was among the most important places in all the world for a total of more than three thousand years, if you consider its history right up to the end of the Babylonians.

And that, I think, can tell us a lot about the amazing persistence of apocalyptic doomsday fears.

When I was a kid, I was fascinated by astronomy. I wanted to grow up to be an astronomer, and even used a little Dymo labelmaker to make a label that said “Franklin Veaux, Astrophysicist” that I stuck on my bedroom door.

Then I found out that some day, the sun would burn out and the earth would become a lifeless lump of rock orbiting a small, cold cinder. And that all the other stars in the sky would burn out. And that all the stars that would come after them would one day burn out, too.

The sense of despair I felt when I learned that permanently changed me.

Think about everything you know. Think about everything you’ve ever said or done, every cause you believe in, every hero and villain you’ve ever encounter, every accomplishment you’ve ever made.

Now think about all of that mattering as much to the world as the life of an apprentice pot-maker in Ur means to you.

It’s one thing to know we are going to die; we all have to deal with that, and we construct all kinds of myths and fables, all sorts of afterlives where we are rewarded with eternal bliss while people we don’t like are forever punished for doing the things we don’t think they should do. But to die, and then to become irrelevant? To die and to know that everything we dreamed of, did, or stood for was completely forgotten, and humanity just went along without us, not even caring that we existed at all? It’s reasonable, I think, for people to experience a sense of despair about that.

But, ah! What if this is the End of Days? What if the world will cease to be in our lifetimes? Now we will never experience that particular fate. Now we no longer have to deal with the idea that everything we know will fade away. There will be no more generations a thousand or ten thousand years hence to have forgotten us; we’re it.

Just think of all the advantages of living in the End Days. We don’t have to face the notion that not only ourselves, but our ideas, our values, our morality, our customs, our traditions, all will fade away and people will get along just fine without us.

And think of the glory! There is a certain reflected glory just in being a person who witnesses an epic thing, even if it’s only from the sidelines. Imagine being in the Afterlife, and having Socrates and Einstein and Buddha saying to us, “Wow, you were there when the Final Seal was broken? That’s so cool! Tell us what it was like?”

Human nature being what it is, there’s also that satisfaction that comes from watching all the world just burn down around you. That will teach them, all those smug bastards who disagreed with us and lived their lives differently from the way we did! As fucked-up as it may be, there’s comfort in that.

Most of us, I suspect, aren’t really equipped to deal with the notion that everything we believe is important will probably turn out not to be. If we were to find ourselves transported a thousand, two thousand, ten thousand years from now, assuming human beings still exist, they will no doubt be very alien to us–as alien as Chicago would be to an ancient Sumerian.

Most of us, I suspect, aren’t really equipped to deal with the notion that everything we believe is important will probably turn out not to be. If we were to find ourselves transported a thousand, two thousand, ten thousand years from now, assuming human beings still exist, they will no doubt be very alien to us–as alien as Chicago would be to an ancient Sumerian.

They won’t speak our language, or anything like it; human languages rarely last more than six hundred years or more. Everything we know will be not only gone, but barely even recognized…if there’s anything left of, say, New York City, it will likely not exist much beyond an archaeological dig and some dry scholarly papers full of conjecture and misinformation. For people who live believing in tradition and hierarchy and authority and continuity, the slow and steady evaporation of all those things is worse than the idea of death. Belief in the End Times is a powerful salve to all of that.

Given the transience of all human endeavor, it makes a certain kind of sense. The alternative, after all, is…what? Cynicism? Nihilism? If everything that we see, do, think, feel, believe, fight for, and sacrifice for is going to mean as much to future generations as the lives of the citizens of Ur four thousand years ago mean to us, what’s the point of any of it? Why believe in anything?

Which, I think, misses the point.

We live in a world of seven billion people, and in all that throng, each of us is unique. We have all spent tens of billions of years not existing. We wake up in the light, alive and aware, for a brief time, and then we return to non-existence. But what matters is that we are alive. It’s not important if that matters a thousand years from now, any more than it matters that it wasn’t important a thousand years ago; it does matter to us, right here, right now. It matters because the things we believe and the things we do have the power to shape our happiness, right here, and if we can not be happy, then what is the point of this brief flicker of existence?

Why should we fight or sacrifice for anything? Because this life is all we have, and these people we share this world with are our only companions. Why should we care about causes like, say, gay rights–causes which in a thousand years will mean as much as campaigns to allow women to appear on stage in Shakespeare’s time? Because these are the moments we have, and this is the only life that we have, and for one group of people to deprive another group of people the opportunity to live it as best suits them harms all of us. If we are to share this world for this brief instant, if this is all we have, then mutual compassion is required to make this flicker of awareness worthwhile. This, ultimately, is the antidote to the never-ending stream of apocalyptic prophesy.