When my friend Jan was visiting a couple of weekends back, I decided to do something I’ve not done in the three years since I’ve been in Atlanta: play tourist.

Atlanta is not exactly the tourist Mecca that, say, Orlando, with its fun frolicksome army of intellectual propery attorneys, is. Nevertheless, it is home to some interesting places, including the world’s largest indoor aquarium and to Oakwood Cemetery, an old 19th-century graveyard with a fascinating history.

The place was founded in 1850. In 1864, Confederate general John B. Hood directed the Battle of Atlanta from within the cemetery (a fitting place, one might argue, from which the leaders of the agrarian South could conduct their ruinous war against an industrialized opponent). Today, it’s a public park, situated smack in downtown Atlanta’s runaway urban sprawl.

And it’s beautiful.

The entrance to the cemetery is gorgeous, all Victorian brick walkways and enormous oak trees. The back of the cemetery descends a rolling hill in carefully designed terraces:

The place is so interesting, in fact, that when dayo came into town for Frolicon, I brought her there as well.

The rest of this post has a very large number of massively bandwidth-crushing pictures, so I’ll put most of them behind cuts for your browsing pleasure.

As we wandered through the cemetery, which is huge beyond reason, one of the things that struck me was how much of a society’s social values and social norms are reflected in the way a society commemorates its dead.

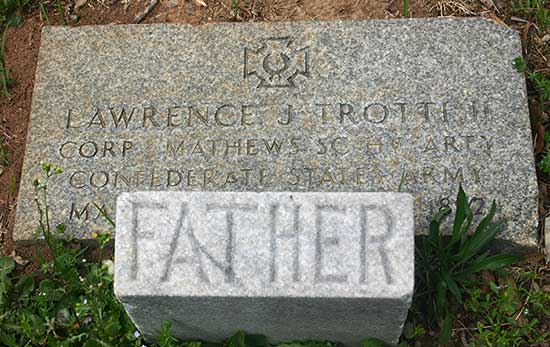

Everything from gender roles to priorities to class hierarchies can be seen reflected in the headstones of an old graveyard. What are we to make, for example, of this family plot, which delineates expectations about gender and family norms with astonishing starkness:

The plot is laid out exactly as you see it here, with the markers for mother and son flanking the marker for father. The patriarch of the family gets a marker and a headstone; the mother and son, just simple markers, no name, no date, nothing. “Mother.” “Son.” Their roles, not their names, are the only things that matter. I thought for a while that perhaps they weren’t even here, and had been interred elsewhere–but why, then, keep the markers at all?

Many of the headstones showed more concern with the deceased’s role in the family than with the deceased as an individual. This fancy, elaborately-carved headstone reads ‘Our Mother,’ something that was clearly important to the family members who commissioned it, but we are left without any clue about who she was:

This tiny headstone, barely six inches across, does a little better. We’re told who the person is, even if we’re left scratching our heads about when she lived and when she died.

The Askew headstone memorializes the members of the Askew family, but in a strange way, listing them only by their initials.

I’m not quite sure what the bottom line means. “R.E.”, “A.C”, and “C.R.” are presumably first and middle initials (the last name for all of them being, I hypothesize, “Askew”), but how to read “W.F-E-A”?

There were a few puzzlers. This marker, which measures perhaps three or four inches wide, was almost completely missable. I assume that the “A.H.H.” represents the initials of the person who’s buried here, but I’m not 100% certain of that. The granite looks somewhat the worse for wear, and seems to have had an encounter or two with a power lawn mower at some point in its past. (“Yeah, I might be chipped, but man, you should see the other guy!”)

There were a few puzzlers. This marker, which measures perhaps three or four inches wide, was almost completely missable. I assume that the “A.H.H.” represents the initials of the person who’s buried here, but I’m not 100% certain of that. The granite looks somewhat the worse for wear, and seems to have had an encounter or two with a power lawn mower at some point in its past. (“Yeah, I might be chipped, but man, you should see the other guy!”)

I’m curious, in a melancholy sort of way, who “A.H.H.” was. How does one reduce the entire life of a human being to three letters carved in stone? We create headstones to memorialize the dead, but who was “A.H.H.”? Who were the “Mother” and “Son” of Mr. Trotti? How does a culture even come to a place where a person’s assigned gender and familial roles become more important than who that person is as a human being?

A headstone that does not memorialize seems to me to be a profoundly useless artifact indeed. The world is filled with mothers and grandmothers, fathers and sons, but every single one of them is unique; it is the uniqueness of each person, not the sameness of the roles which they fill, that is cause for celebration.

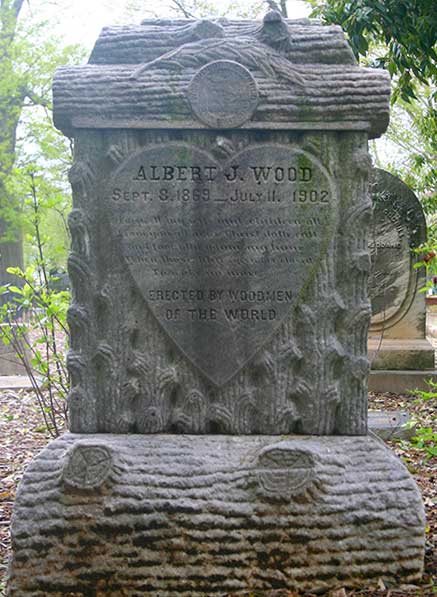

In one plot, a bit off the path, I found a marker that is a visual pun on the name of the plot’s inhabitant. Behold the headstone of Albert J. Wood, a play on words carved into solid granite:

Okay, so it’s not really a visual pun, though it would have been very cool had it been; who has both the courage and the sense of humor to make his headstone into a word play? If such a person exists, I’d very much like to meet him.

Okay, so it’s not really a visual pun, though it would have been very cool had it been; who has both the courage and the sense of humor to make his headstone into a word play? If such a person exists, I’d very much like to meet him.

There are similar headstones scattered throughout Oakland Cemetery, each designed to look like it’s made of wood and each reading “Erected by Woodmen of the World”.

I looked up Woodmen of the World on my iPhone while dayo and I were there. Turns out that it’s the name of a fraternal benefit society kinda sorta related to the Freemasons, founded by a Mason named Joseph Cullen Root in 1890.

It’s dedicated to providing its members with financial assistance, primarily through life insurance policies. One of the benefits of membership is–or was, until the program was dropped in the 1920s–a free headstone, carved in the distinctive likeness of a wood stump or a pile of logs. These headstones dot old cemeteries from the late 1800s and early 1900s all over the country, and many of them can be found in Oakland Cemetery.

The Woodmen of the World are still around. They’re headquartered in Omaha, Nebraska, the town in which they were founded, and offer life insurance, college savings programs, youth programs, investment services, and that sort of thing.

They used to run radio and television stations (odd bit of trivia: Johnny Carson got his start in TV on a Woodmen-owned television station) until the Supreme Court ruled that they could not simultaneously keep the stations and also retain their non-profit status.

The human brain is remarkably adept at recognizing, creating, and using symbols. Our language consists of nothing but an abstract set of symbols, and the fact that our brains are so highly tuned for pattern recognition perhaps suggests that it is inevitable we should come to use symbols everywhere.

The human brain is remarkably adept at recognizing, creating, and using symbols. Our language consists of nothing but an abstract set of symbols, and the fact that our brains are so highly tuned for pattern recognition perhaps suggests that it is inevitable we should come to use symbols everywhere.

Oakland Cemetery is filled with symbols. The lion’s head is a recurring one, appearing on the doors and gates of mausoleums and even on some headstones. I like this one, and a similar lion with a ring in its teeth cast into the metal doors of a large mausoleum in the cemetery’s wealthier district.

And oh, yes, cemeteries, like cities, have desirable and undesirable districts, tony neighborhoods and low-rent slums. More on that in Part II of this post.

Many of the symbols that adorn the markers and plots in Oakland Cemetery are what you’d expect; Freemason symbols and this kind of floral relief thing are extremely common.

The word “Resurgam” below the casting here means, as Google informed me, “I Shall Rise Again” in Latin. In the 1870s, two submarines, “Resurgam I” and “Resurgam II,” were designed and built as naval weapons in Birkenhead, England. The first naval submarine to have successfully sunk an enemy ship in combat, the Confederate sub H. L. Hunley, had demonstrated the possibility of submarine warfare (and sunk itself in the process, killing its crew) about ten years earlier.

Neither Resurgam ever saw combat; one was simply a proof-of-concept, and the other was lost while making its way to a Royal Navy demonstration, when it took on water in high seas and failed to live up to its name.

But I digress.

It’s the subtler things, the more personal and intimate symbols, that are the most heart-wrenching. A cemetery is witness to countless little rituals of loss, of grief, of remembrance. Unlike the impersonal, common symbols that decorate most of the headstones (“This person was a Freemason!” “This person was a veteran!” “This person worshipped in this church!”), these symbols speak in a whisper, a private language understood only to the people for whom they matter.

Near one edge of Oakland Cemetery is this statue of an angel, silent witness to the tragedy of death and the rituals shaped by grief.

This is a place where people go to keep alive the memory of those they have loved. I don’t understand the meanings of the symbols here. I don’t know what the duck represents, or what the key fits, or what lies behind the row of coins–some of them new, some quite old–that have so carefully been lined up on the marble. And maybe that’s appropriate. The meaning here isn’t intended for me. Each of these things is uniquely personal, a visceral public expression of private agony. The people whose lives ended in this plot of land were at one time vital, essential human beings, and the little rituals of remembrance that play out here is an honoring of their lives in a language that is meant for nobody else.

By far the most beautiful and the most saddening of all the things I saw in the cemetery, though, is this statue of two lovers sitting beside one another.

Everything about this statue is an exquisite expression of love. Even the casual intimacy of the pose–he is combing her hair–speaks to the connection shared by these people.

There is an inscription on the bottom of the statue:

Six simple words, that express the things these people felt wIth greater depth and clarity than the most eloquent poet. Pain and loss in our society have become simply another revenue stream; the funeral home measures out its customers’ grief in a mechanized, standardized way (“for our Class C funeral package, you have your choice of one of four headstone designs from column three of this list, plus your choice of any of the caskets between pages eight and twelve of your brochure. You can upgrade to one of the caskets shown on page fourteen for an additional fee.”); memorials like this make it personal again, show us that of all the millions of people who die every year, each one of them is a tragedy.

We become so numb to the routine business of death that we have lost sight of the fact that every single one is accompanied by a real human cost; that each plot in this enormous cemetery is a point of acute suffering and loss of a part of someone’s soul.

There are small round pebbles around the base and back of this statue, and flowers that look recently placed. There’s even a small pebble in her hand, nestled in where it rests on her lap. Each of these is an honoring of the person she was an an act that cherishes the love these two people shared, each made at the cost of keeping alive the pain of loss. He is not here yet; she died in 2006, and he has already made the choice to lie next to her.

Seeing this memorial reminded me again that this is not okay, and made me glad once more that I am in love with a dragonslayer.

First of all, I love the Doctor Who reference you sneaked in there. I’ll never be able to go to my favorite cemetery again without thinking of that episode.

There’s a headstone in Swan Point Cemetery up here that make me so sad that I try not to even go to its spot – the marker of a brother and sister.

Anytime I’ve seen it, there’s always a new batch of small toys snuggled in bed with them.

what a wonderful, sad photo! i’m obsessed w/funerary sculpture too!

Any cemetery with big old monuments is fun, the older the better. Swan Point is my favorite, but they don’t allow photography and due to the fact that H. P. Lovecraft is buried there and tends to attract some troublemakers, they’re hyper-vigilant with security patrols, so I tend to get kicked out at some point when I do go there.

i just added you on Flickr..i’m spiralflmz there..many cemeteries on my page as well. swan point photos are wonderful!!

First of all, I love the Doctor Who reference you sneaked in there. I’ll never be able to go to my favorite cemetery again without thinking of that episode.

There’s a headstone in Swan Point Cemetery up here that make me so sad that I try not to even go to its spot – the marker of a brother and sister.

Anytime I’ve seen it, there’s always a new batch of small toys snuggled in bed with them.

My Great-Grandfather, in fact, has a Woodmen of the World headstone out in a quiet cemetery in west Texas. Some years ago, I, too, researched the organization and came up with the same information.

My wife, as a favor to my aunt, computerized a listing of the local cemetery. Sometimes, just the raw information makes you sad. Two children dead on the same day.

Another good post, Tacit.

My Great-Grandfather, in fact, has a Woodmen of the World headstone out in a quiet cemetery in west Texas. Some years ago, I, too, researched the organization and came up with the same information.

My wife, as a favor to my aunt, computerized a listing of the local cemetery. Sometimes, just the raw information makes you sad. Two children dead on the same day.

Another good post, Tacit.

This is one of my all time favorites:

The story is that the husband is/was (not sure at this point) a sculptor. The wife’s 3 favorite things were books, cats, and talking to new people, so he created a memorial where she had all three. There’s room to sit beside her on the bench.

This is one of my all time favorites:

The story is that the husband is/was (not sure at this point) a sculptor. The wife’s 3 favorite things were books, cats, and talking to new people, so he created a memorial where she had all three. There’s room to sit beside her on the bench.

wonderful, as are all the comments!

might as well leave one also..this broke my heart, putting flowers in her hand in winter.

wonderful, as are all the comments!

might as well leave one also..this broke my heart, putting flowers in her hand in winter.

what a wonderful, sad photo! i’m obsessed w/funerary sculpture too!

Recently, , and I went to a rambling mausoleum in Portland. We had to sign in to visit a loved one since they are more carefully guarding the entrance.. and I did so… We wandered the 5 or six stories and long hallways, small plazas, and chapels of the structure for about 2 hours I think. It was beautiful. I found the full casket size sections of wall to be a little creepy and was far more comfortable with the ashes, urns, and memorials. What history of families there! ..beautiful old names ..and stories. Some sections had shrines of trinkets or toys place on them.. others had cards and letters from every holiday during the past year to the dead daughter of a man writing her at the age of 95 when she has been dead for 40 years.

It was a moving experience. I would like to expose myself to more such activities.

Recently, , and I went to a rambling mausoleum in Portland. We had to sign in to visit a loved one since they are more carefully guarding the entrance.. and I did so… We wandered the 5 or six stories and long hallways, small plazas, and chapels of the structure for about 2 hours I think. It was beautiful. I found the full casket size sections of wall to be a little creepy and was far more comfortable with the ashes, urns, and memorials. What history of families there! ..beautiful old names ..and stories. Some sections had shrines of trinkets or toys place on them.. others had cards and letters from every holiday during the past year to the dead daughter of a man writing her at the age of 95 when she has been dead for 40 years.

It was a moving experience. I would like to expose myself to more such activities.

Any cemetery with big old monuments is fun, the older the better. Swan Point is my favorite, but they don’t allow photography and due to the fact that H. P. Lovecraft is buried there and tends to attract some troublemakers, they’re hyper-vigilant with security patrols, so I tend to get kicked out at some point when I do go there.

Wonderful post! For the solution of one of the mysterious headstones, you need look no further than Monty Python: “He who is valiant and pure of spirit may find the Holy Grail in the Castle of A.H.H.”

Wonderful post! For the solution of one of the mysterious headstones, you need look no further than Monty Python: “He who is valiant and pure of spirit may find the Holy Grail in the Castle of A.H.H.”

Now that I am in Savannah, I go over to Bonadventure alot. It has such a similar feel to it in parts, with the big old mausoleums…But, I lived at the end of Oakland Ave. for 10 years, and would go up to the cemetery to do homework and just walk around. One of the most interesting parts to me was the jewish section. They have the graves packed in so tightly, you can barely squeeze between the stones. The caskets must be quite literally head to toe. It always made me a bit sad…

I also liked to go sit in the back corner kinda near where a small gate leads out the back and now onto the marta tracks… I used to wonder what that gate led to a hundred years ago… and that strange and sorta creepy decayed building that is towards the middle back… always wondered what it was.

I have some gothic/light fetish photos that were taken (very sneakily) at Oakland a few years back if you ever want to see them 🙂

Thanks for all the info, that’s more than I ever learned, even going there regularly…

Now that I am in Savannah, I go over to Bonadventure alot. It has such a similar feel to it in parts, with the big old mausoleums…But, I lived at the end of Oakland Ave. for 10 years, and would go up to the cemetery to do homework and just walk around. One of the most interesting parts to me was the jewish section. They have the graves packed in so tightly, you can barely squeeze between the stones. The caskets must be quite literally head to toe. It always made me a bit sad…

I also liked to go sit in the back corner kinda near where a small gate leads out the back and now onto the marta tracks… I used to wonder what that gate led to a hundred years ago… and that strange and sorta creepy decayed building that is towards the middle back… always wondered what it was.

I have some gothic/light fetish photos that were taken (very sneakily) at Oakland a few years back if you ever want to see them 🙂

Thanks for all the info, that’s more than I ever learned, even going there regularly…

i just added you on Flickr..i’m spiralflmz there..many cemeteries on my page as well. swan point photos are wonderful!!

I’ve been thinking about this, and about the DragonSlayer essay, and have come to a conclusion: I have no issues with death becoming optional, but I have huge issues with death becoming impossible. I don’t want to live forever.

I don’t see any time when death is impossible. Physical issues aside, the whole point of making death optional in the first place is that nothing about it should ever be mandatory.

I’ve been thinking about this, and about the DragonSlayer essay, and have come to a conclusion: I have no issues with death becoming optional, but I have huge issues with death becoming impossible. I don’t want to live forever.

I don’t see any time when death is impossible. Physical issues aside, the whole point of making death optional in the first place is that nothing about it should ever be mandatory.