| Part 1 of this saga is here. |

Part 7 of this saga is here. |

| Part 2 of this saga is here. |

Part 8 of this saga is here. |

| Part 3 of this saga is here. |

Part 9 of this saga is here. |

| Part 4 of this saga is here. |

Part 10 of this saga is here. |

| Part 5 of this saga is here. |

Part 11 of this saga is here. |

| Part 6 of this saga is here. |

Part 12 of this saga is here. |

We are nearing the end of this tale, gentle readers, but what an end it is.

Bunny and I piled into the Adventure Van, headed to where we had heard of a large ghost town called Bodie, an 1800s gold-mining town in the rugged mountains of eastern California. Bodie was a–

“Hey, pull over!” Bunny said.

I pulled over near this apparently abandoned(?) building advertising bail bond services. Seemed legit.

We took some pictures, tromped about for a bit, then climbed into the Adventure Van once more, headed for Bodie. Bodie was a thriving gold mining town with more than ten thousand residents at its peak, located at more than eight thousand feet elevation in the Sierra Nevada mountains. It was a huge and fantastically profitable gold mining town, producing tens of millions of dollars (in 1850s dollars!) in gold. Miners were paid $4 a week for dangerous, heavy physical labor under grueling conditions; of that $4, $2.75 per week was deducted for room and board.

You get there by following a narrow dirt track up and up and up into the mountain. Bodie is well off the beaten path, in much the same way that a manned excursion to Mars is not a jaunt down to the local grocery store. Fortunately, it was not a terribly steep grade–stagecoaches loaded with gold had to be able to make the trip, after all–and the Adventure Van was up to the journey with a minimum of grumbling.

We drove for a couple of hours. “I hope this is worth it,” I said. Bunny said something noncommittal.

It was worth it.

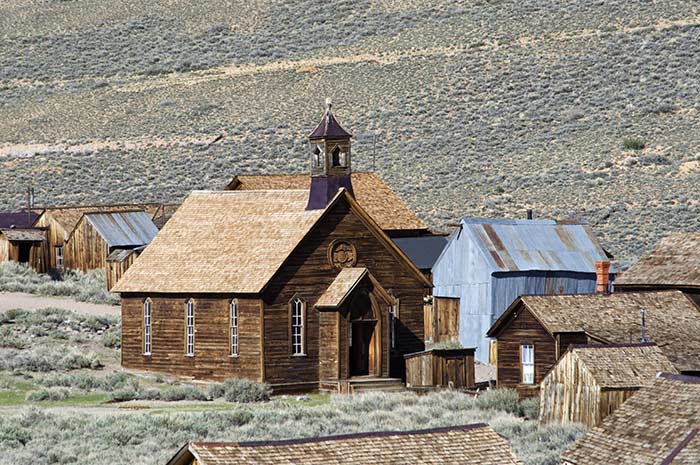

When at long last you’ve traveled up to the summit of the Bodie Hills, the first thing you see from the road, aside from a “State Park” sign, is this.

This was the jackpot, the mother lode, the Platonic ideal of a Western ghost town. This, gentle readers, truly was the bee’s knees.

We parked–with, I must confess, some excitement–and left the comforting shelter of the Adventure Van into the dry, dusty heat of Bodie, California.

The moment you step out of the parking lot, thoughtfully provided for you by the California Department of Parks and Recreation, you walk up a slight rise and see…this.

This small picture can not do justice to how amazing this place is. Click on the picture to see a (much) bigger version.

Less than a quarter of the town remains; the rest burned to the ground quite some years ago. At its peak, the town had sixty-five saloons, numerous brothels, and several churches that one could go to for absolution of one’s sins, which were numerous indeed. Bodie was by all accounts a very violent place; common hobbies included murder and various lesser crimes. According to one of the tour guides we spoke to, it’s not uncommon for people who do heavy labor at high altitudes without proper acclimatization to suffer psychotic breaks.

Bodie had an extensive network of roads, all unpaved. Again, click on the picture to embiggen.

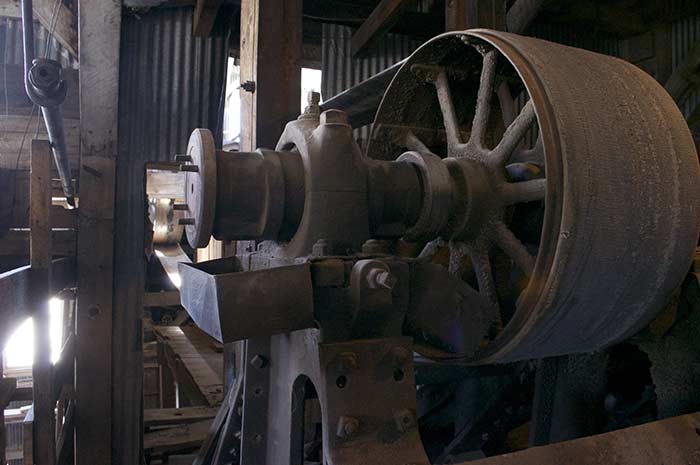

The large gray building on the left-hand side of the first picture is the stamping mill, the entire reason for Bodie’s existence. I plan to write an entire post about that stamping mill. Raw gold ore was carried to the stamping mill, where the rock was crushed to a powder as fine as flour, and gold was extracted from it by a process that was absolutely and completely bonkers and showed a careless–indeed reckless–disregard for the life, health, and safety of the people who worked there. More on that later.

Bunny and I eventually spent two days in Bodie, wandering around taking pictures–many hundreds and hundreds of pictures. I’ve condensed the trove down to about eighty or so, which will likely take several posts to work through. Apologies in advance for what I’m about to do to your bandwidth, O readers.

Life in Bodie was not particularly pleasant. The air at eight thousand feet is thin. During the summer, the temperature routinely exceeds a hundred degrees Fahrenheit; during the winter, twenty feet of snow is not uncommon. Everything from building supplies to construction equipment had to be carried up the mountain. There was one road that climbed into Bodie from the west, ran straight through town, and exited to the east. Naturally, as it was the only way into or out of Bodie, it was a toll road (buggies 25 cents; carriages 75 cents; discounts for firewood and mining gear).

The houses we saw tended to be quite small and simple, save for this one, a veritable mansion belonging to the overseer of the stamping mill. You can click this picture to embiggen it, too.

The tour guide didn’t say, but I suspect the stamping mill overseer made rather more than $4 a week.

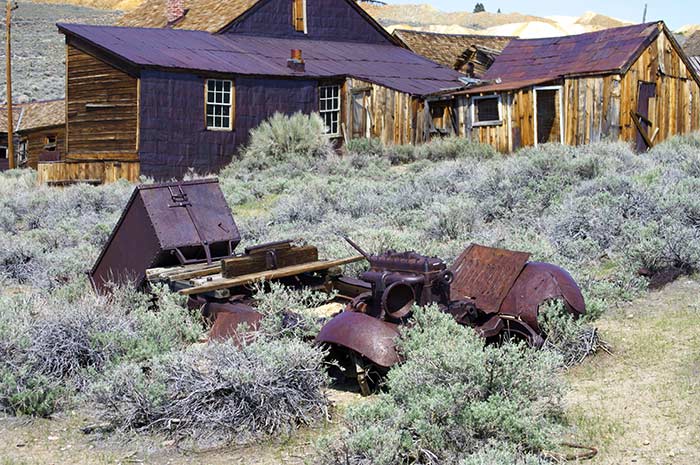

This place was more typical of the houses in Bodie.

You’ll notice the remnants of derelict machinery in the foreground. Bodie is littered with abandoned equipment rusting quietly into the desert; it’s everywhere.

Even with all its violence and squalor, Bodie was the absolute pinnacle of Victorian technology. It was on the cutting edge of mining industry, and there was no new, experimental mining tech they would not use if it would increase the rate at which they could mine or process ore. The town of Bodie was a bit like the Silicon Valley of the 1800s–it was absolutely state of the art for new machinery and new techniques.

Bodie was abandoned rather abruptly when the mines stopped being profitable. All that tech was left where it was, because Bodie is so remote and inhospitable that it simply wasn’t worth carting it all back down the mountain again. So now it lies scattered everywhere, remnants of what was once innovative, up-to-the-minute industrial know-how.

In fact, I’ll probably dedicate an entire post just to various bits of cast-off technology we found littering the countryside.

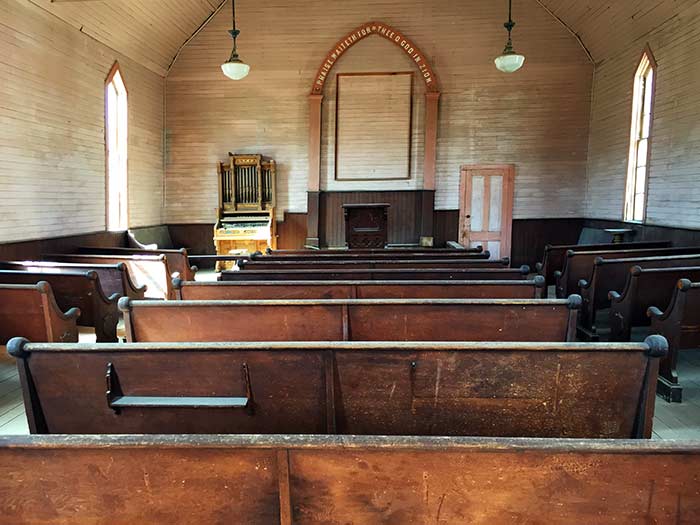

At one time, Bodie sported several churches. Today, only the Methodist church still stands.

The writing on the archway in the back reads “Praise waiteth for thee O God in Zion.”

The buildings are in remarkably good shape because of the foresight of one person, James S. Cain, who, as people left, offered to buy their houses or shops for a dollar. Since they were leaving anyway, and there was little of value remaining, almost everyone agreed. He continued to work the mine, making far less money than it had produced at its peak but still enough for him to turn a modest profit. Later, he hired guards to protect the deserted town from looters and vandals.

In the early 1960s, what was left of Bodie became a protected state park.

Being a closely-packed, densely-populated town made entirely of wood in deep desert, Bodie had several fire stations, only one of which remains.

In the 1930s, after the town was all but completely deserted, a fire swept through it, destroying a significant percentage of the remaining buildings, including all of the brothels (of which there were once many) and all of what had once been Chinatown.

Only a few of the buildings along what used to be Main Street survive, including a tavern and a gym.

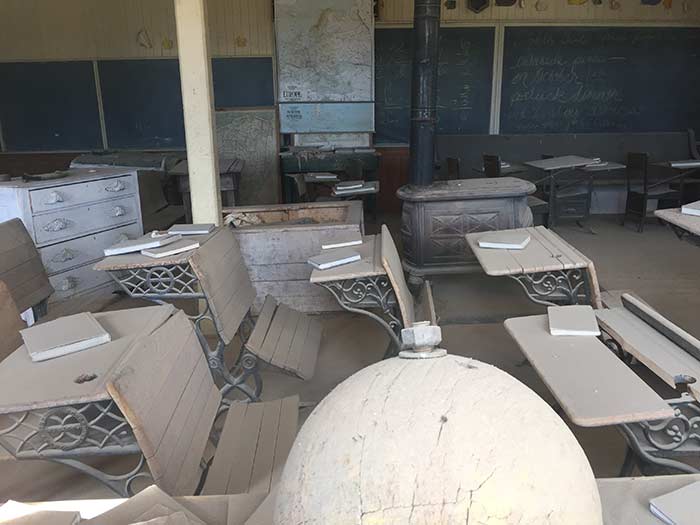

At its peak, Bodie had a significant enough population of children that it featured a large, two-story school. I’m not sure I would have tried to raise children here, but hey, that’s me.

This is what happens if you leave an 1850s-era globe in a window exposed to harsh ultraviolet light for over a century. I think this is amazing.

The sun really is brutal at 8,000 feet. Bunny and I both got sunburned right through our clothes–something that, I gather, is quite common at that altitude. Wish I’d have known about it before we were there!

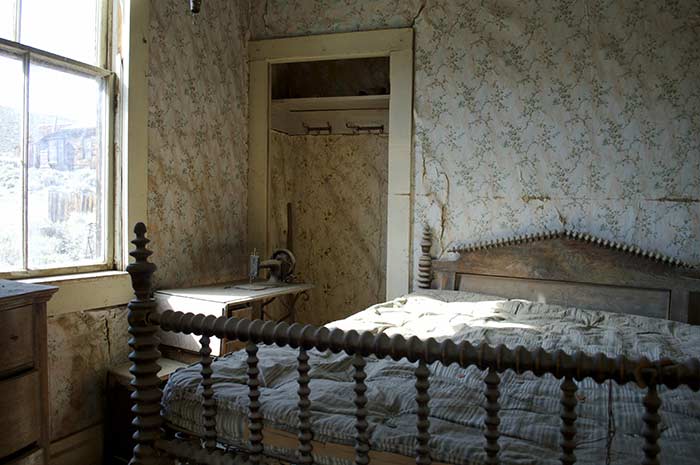

The mill overseer’s digs, as I mentioned before, were quite luxurious.

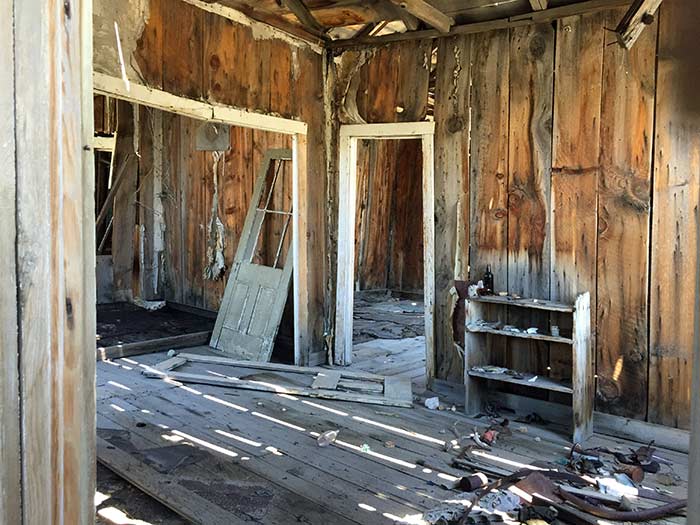

“Luxury” is not the first word that springs to mind to describe most of the other housing, but the accommodations weren’t really that bad, considering. That is, if you can get past the harsh environment with its blistering heat and brutal cold, the violence, the long hours of backbreaking labor without insurance or OSHA regulation, and the lack of medical care or sanitation.

It’s hard to imagine what this place must’ve been like when it was home to tens of thousands of people, when we see only the few remnants that are left.

One of the nicest houses we found was located a good distance from the mill that was the hub of Bodie’s economic activity. It was huge, even larger than the mill overseer’s mansion, and crafted to a much higher standard. I’d love to know the story of whoever lived there.

Bodie had its own prison–necessary given the proximity to extremely valuable resources, the general criminal proclivities of many of its inhabitants, and the tendency of hard manual labor at high altitude to produce psychosis.

It also had a rather large cemetery, which included a special wing just for infants. Infant mortality in Bodie was frighteningly high, with cholera one of the leading causes of death.

The Victorians knew rather a lot about steam technology but rather less about medicine. All the buildings had outhouses; there was no sewer system. Outhouses were built near houses, and higher areas were more desirable for houses. Water came from wells, which were easier to dig in low areas. So a common pattern you see over and over throughout Bodie is outhouses located just up the hill from a well.

We arrived in Bodie late in the afternoon and soon had to make our exit. I asked one of the park rangers where the closest town was. She said we could go back out the way we came, which would take us to a town about an hour away, or we could continue through the town and go down the other side of the mountain to get to Aurora.

We opted for the latter. It turns out that either I radically misheard her, or she was playing a trick on us. Aurora, you see, is a ghost town in Nevada, even more inhospitable and inaccessible than Bodie.

We got to the base of the mountain and discovered we could go no further. The Adventure Van simply wasn’t up to what passed for a road. So we camped for the night at the base of the hill, near a sign that warned us not to travel any farther.

The next day, we drove back up the mountain to Bodie, which will be the subject of the next chapter.

Like this:

Like Loading...