The notion of “uploading”–analyzing a person’s brain and then modeling it, neuron by neuron, in a computer, thereby forever preserving that person’s knowledge and consciousness–is a fixture of transhumanist thought. In fact, self-described “futurists” like Ray Kurzweil will gladly expound at great length about how uploading and machine consciousness are right around the corner, and Any Day Now we will be able to live forever by copying ourselves into virtual worlds.

I’ve written extensively before about why I think that’s overly optimistic, and why Ray Kurzweil pisses me off. Our understanding of the brain is still remarkably poor–for example, we’re only just now learning how brain cells called “glial cells” are involved in the process of cognition–and even when we do understand the brain on a much deeper level, the tools for being able to map the connections between the cells in the brain are still a long way off.

In that particular post, I wrote that I still think brain modeling will happen; it’s just a long way off.

Now, however, I’m not sure it will ever happen at all.

I love cats.

Many people love cats, but I really love cats. It’s hard for me to see a cat when I’m out for a walk without wanting to make friends with it.

It’s possible that some of my love of cats isn’t an intrinsic part of my personality, in the sense that my personality may have been modified by a parasite commonly found in cats.

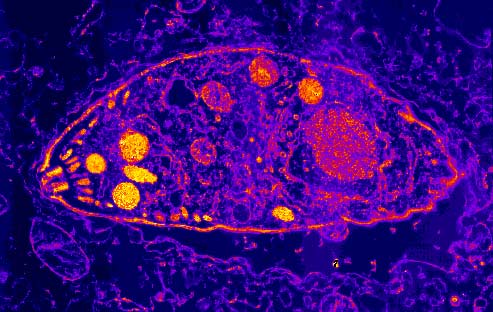

This is the parasite, in a color-enhanced scanning electron micrograph. Pretty, isn’t it? It’s called Toxoplasma gondii. It’s a single-celled organism that lives its life in two stages, growing to maturity inside the bodies of rats, and reproducing in the bodies of cats.

When a rat is infected, usually by coming into contact with cat droppings, the parasite grows but doesn’t reproduce. Its reproduction can only happen in a cat, which becomes infected when it eats an infected rat.

To help ensure its own survival, the parasite does something amazing. It controls the rat’s mind, exerting subtle changes to make the rat unafraid of cats. Healthy rats are terrified of cats; if they smell any sign of a cat, even a cat’s urine, they will leave an area and not come back. Infected rats lose that fear, which serves the parasite’s needs by making it more likely the rat will be eaten by a cat.

Humans can be infected by Toxoplasma gondii, but we’re a dead end for the parasite; it can’t reproduce in us.

It can, however, still work its mind-controlling magic. Infected humans show a range of behavioral changes, including becoming more generous and less bound by social mores and customs. They also appear to develop an affinity for cats.

There is a strong likelihood that I am a Toxoplasma gondii carrier. My parents have always owned cats, including outdoor cats quite likely to have been exposed to infected rats. So it is quite likely that my love for cats, and other, more subtle aspects of my personality (bunny ears, anyone?), have been shaped by the parasite.

So, here’s the first question: If some magical technology existed that could read the connections between all of my brain cells and copy them into a computer, would the resulting model act like me? If the model didn’t include the effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection, how different would that model be from who I am? Could you model me without modeling my parasites?

It gets worse.

The brain models we’ve built to date are all constructed from generic building blocks. We model neurons as though they are variations on a common theme, responding pretty much the same way. These models assume that the neurons in Alex’s head behave pretty much the same way as the neurons in Bill’s head.

To some extent, that’s true. But we’re learning that there can be subtle genetic differences in the way that neurons respond to different neurotransmitters, and these subtle differences can have very large effects on personality and behavior.

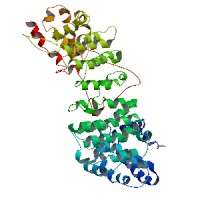

Consider this protein. It’s a model of a protein called AVPR-1a, which is used in brain cells as a receptor for the neurotransmitter called vasopressin.

Consider this protein. It’s a model of a protein called AVPR-1a, which is used in brain cells as a receptor for the neurotransmitter called vasopressin.

Vasopressin serves a wide variety of different functions. In the body, it regulates water retention and blood pressure. In the brain, it regulates pair-bonding, stress, aggression, and social interaction.

A growing body of research shows that human beings naturally carry slightly different forms of the gene that produce this particular receptor, and that these tiny genetic differences result in tiny structural differences in the receptor which produce quite significant differences in behavior. For example, one subtle difference in the gene that produces this receptor changes the way that men bond to partners after sex; carriers of this particular genetic variation are less likely to experience intense pair-bonding, less likely to marry, and more likely to divorce if they do marry.

A different variation in this same gene produces a different AVPR-1a receptor that is strongly linked to altruistic behavior; people with that particular variant are far more likely to be generous and altruistic, and the amount of altruism varies directly with the number of copies of a particular nucleotide sequence within the gene.

So let’s say that we model a brain, and the model we use is built around a statistical computation for brain activation based on the most common form of the AVPR-1a gene. If we model the brain of a person with a different form of this gene, will the model really represent her? Will it behave the way she does?

The evidence suggests that, no, it won’t. Because subtle genetic variations can have significant behavioral consequences, it is not sufficient to upload a person using a generic model. We have to extend the model all the way down to the molecular level, modeling tiny variations in a person’s receptor molecules, if we wish to truly upload a person into a computer.

And that leads rise to a whole new layer of thorny moral issues.

There is a growing body of evidence that suggests that autism spectrum disorders are the result in genetic differences in neuron receptors, too. The same PDF I linked to above cites several studies that show a strong connection between various autism-spectrum disorders and differences in receptors for another neurotransmitter, oxytocin.

Vasopressin and oxytocin work together in complex ways to regulate social behavior. Subtle changes in production, uptake, and response to either or both can produce large, high-level changes in behavior, and specifically in interpersonal behavior–arguably a significant part of what we call a person’s “personality.”

So let’s assume a magic brain-scanning device able to read a person’s brain state and a magic computer able to model a person’s brain. Let’s say that we put a person with Asperger’s or full-blown autism under our magic scanner.

What do we do? Do we build the model with “normal” vasopressin and oxytocin receptors, thereby producing a model that doesn’t exhibit autism-spectrum behavior? If we do that, have we actually modeled that person, or have we created an entirely new entity that is some facsimile of what that person might be like without autism? Is that the same person? Do we have a moral imperative to model a person being uploaded as closely as possible, or is it more moral to “cure” the autism in the model?

In the previous essay, I outlined why I think we’re still a very long ways away from modeling a person in a computer–we lack the in-depth understanding of how the glial cells in the brain influence behavior and cognition, we lack the tools to be able to analyze and quantify the trillions of interconnections between neurons, and we lack the computational horsepower to be able to run such a simulation even if we could build it.

Those are technical objections. The issue of modeling a person all the way down to the level of genetic variation in neurotransmitter and receptor function, however, is something else.

Assuming we overcome the limitations of the first round of problems, we’re still left with the fact that there’s a lot more going on in the brain than generic, interchangeable neurons behaving in predictable ways. To actually copy a person, we need to be able to account for genetic differences in the structure of receptors in the brain…

…and even if we do that, we still haven’t accounted for the fact that organisms like Toxoplasma gondii can and do change the behavior of the brain to suit their own ends. (I would argue that a model of me that was faithful clear down to the molecular level probably wouldn’t be a very good copy if it didn’t include the effects that the parasite have had on my personality–effects that we still have no way to quantify.)

Sorry, Mr. Kurzweil, we’re not there yet, and we’re not likely to be any time soon. Modeling a specific person in a brain is orders of magnitude harder than you think it is. At this point, I can’t even say with certainty that I think it will ever happen.

First, let me talk about what I mean when I use the word “courage.”

First, let me talk about what I mean when I use the word “courage.” Now, sure, moving with courage is not always rewarded. Again, if there were no possibility of hurt or loss, there would be no virtue in courage. Yes, you might reach out for what you want and come up short. You might be rejected. You might be hurt. Absolutely.

Now, sure, moving with courage is not always rewarded. Again, if there were no possibility of hurt or loss, there would be no virtue in courage. Yes, you might reach out for what you want and come up short. You might be rejected. You might be hurt. Absolutely.

This is Malala Yousafzai. As most folks are by now aware, she is a 14-year-old Pakistani girl who was shot in the head by the Taliban for the crime of saying that girls should get an education. Her shooting prompted an enormous backlash worldwide, including–in no small measure of irony–among American politicians who belong to the same political party as legislators who say that

This is Malala Yousafzai. As most folks are by now aware, she is a 14-year-old Pakistani girl who was shot in the head by the Taliban for the crime of saying that girls should get an education. Her shooting prompted an enormous backlash worldwide, including–in no small measure of irony–among American politicians who belong to the same political party as legislators who say that

Writers like Sam Harris and Michael Shermer talk about how people in a pluralistic society can not really accept and live by the tenets of, say, the Bible, no matter how Bible-believing they consider themselves to be. The Bible advocates slavery, and executing women for not being virgins on their wedding night, and destroying any town where prophets call upon the citizens to turn away from God; these are behaviors which you simply can’t do in an industrialized, pluralistic society. So the members of modern, industrialized societies–even the ones who call themselves “fundamentalists” and who say things like “the Bible is the literal word of God”–don’t really act as though they believe these things are true. They don’t execute their wives or sell their daughters into slavery. The memes are not as effective at modifying the hosts as they used to be; they have become less virulent.

Writers like Sam Harris and Michael Shermer talk about how people in a pluralistic society can not really accept and live by the tenets of, say, the Bible, no matter how Bible-believing they consider themselves to be. The Bible advocates slavery, and executing women for not being virgins on their wedding night, and destroying any town where prophets call upon the citizens to turn away from God; these are behaviors which you simply can’t do in an industrialized, pluralistic society. So the members of modern, industrialized societies–even the ones who call themselves “fundamentalists” and who say things like “the Bible is the literal word of God”–don’t really act as though they believe these things are true. They don’t execute their wives or sell their daughters into slavery. The memes are not as effective at modifying the hosts as they used to be; they have become less virulent.