If you venture into the polyamory community for long enough, eventually you will encounter someone who says “Polyamory is good because no one person can meet all of your needs. With poly, I can find different people who meet different needs, and so be happier.”

That line of reasoning has always bugged the hell out of me. It seems to me that there is something deeply, profoundly wrong with this argument, but I’ve never really been able to articulate what.

Today, while pondering an entirely different question, it occurred to me. We are, through biology or socialization or both, prone to viewing romantic partners as need fulfillment machines. When we have a need, be it for companionship or for sex or for someone to process with or for someone to (God help us) go bowling with, we look to our partners to meet those needs.

Which is fine, as far as it goes. Indeed, one of the greatest things about being in a romantic relationship is having someone to turn to, someone to co-create with and to be inspired by, someone who will help us as we build our lives.

But it gets a little messed up, I think, when we start with the assumption that our partners are obligated to meet our needs–that that’s what they are there for, and if our needs aren’t being met, our partners have done something wrong.

A lot of folks say that you can never truly be friends with members of the opposite sex. In addition to being extremely heteronormative (does that mean a gay man can’t ever truly be friends with another gay man? That a bisexual woman can’t truly be friends with anyone?), it speaks, I think, to the notion that we tend to view folks through the lens of need fulfillment objects. For instance, there is a common (and misogynistic) narrative that says driving need of men is sex; any man who befriends a woman is, somewhere in his mind, doing so with the expectation that at some point he can get her to fill that need. I could write a book on how profoundly twisted that idea is, but that will have to wait for another time.

I think there are also signs of this objectification in the expectations for the way people behave after a romantic breakup. When a relationship–especially a sexual relationship–ends, there’s a social expectation that the people involved will revile each other; ex-partners who are on good terms with one another tend to be treated as something of an aberrant curiosity, like something we should be looking at from behind a roped-off area in a circus sideshow somewhere. Part of that is certainly that the ending of a relationship can be painful, and we are not really taught how to process emotional pain well; but part of it does point to the notion that if we break up with someone, it’s because that person failed in his or her duties to meet our needs, and why would we want to keep them around? After all, isn’t that a bit like hanging on to a broken toaster or something?

I think there are also signs of this objectification in the expectations for the way people behave after a romantic breakup. When a relationship–especially a sexual relationship–ends, there’s a social expectation that the people involved will revile each other; ex-partners who are on good terms with one another tend to be treated as something of an aberrant curiosity, like something we should be looking at from behind a roped-off area in a circus sideshow somewhere. Part of that is certainly that the ending of a relationship can be painful, and we are not really taught how to process emotional pain well; but part of it does point to the notion that if we break up with someone, it’s because that person failed in his or her duties to meet our needs, and why would we want to keep them around? After all, isn’t that a bit like hanging on to a broken toaster or something?

It seems obvious to me how a partner who is treated as a human being rather than a need fulfillment machine is still valuable even if one’s needs aren’t currently being serviced, but it also feels to me like this is something of a minority opinion.

The tacit view of a partner as a need fulfillment machine explains the way people often deal with problems in a relationship. Many relationships are predicated on the notion that if Alice is involved with Bob, and Bob needs something (particularly if Bob has an emotional need), it is perfectly acceptable for Bob to not only ask for it from Alice but to demand it–and pitch a fit if he doesn’t get it.

The need-based argument for poly (“one person can’t really meet all my needs, so I have more than one!”) is a direct statement of the notion that partners are need fulfillment machines. It assumes as a subtext that getting someone to meet your needs for you is the entire purpose of a romantic relationship, and if one romantic relationship isn’t enough, you turn to more than one.

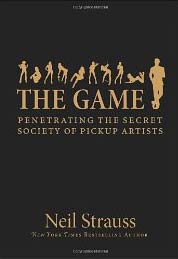

My sweetie zaiah says that kids who go to sex-segregated schools are more likely to treat people of the opposite sex as a kind of faceless, undifferentiated Other than kids who don’t. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but it does seem that adults who see members of the opposite sex as The Other also seem more likely to treat their partners as need fulfillment machines than adults who don’t. Bookstore shelves are groaning under the weight of books that try to paint members of the opposite sex as The Other, some strange alien that you interface with in order to get your needs met, but who aren’t really fully individuated human beings. The Game, The Rules, Why Men Love Bitches…people are drawn to these books to help them puzzle out the mysteries of the user interfaces on these strange, otherworldly things that the can’t understand but nevertheless feel like they need. And from my perspective, it all feels more than a little fucked up.

My sweetie zaiah says that kids who go to sex-segregated schools are more likely to treat people of the opposite sex as a kind of faceless, undifferentiated Other than kids who don’t. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but it does seem that adults who see members of the opposite sex as The Other also seem more likely to treat their partners as need fulfillment machines than adults who don’t. Bookstore shelves are groaning under the weight of books that try to paint members of the opposite sex as The Other, some strange alien that you interface with in order to get your needs met, but who aren’t really fully individuated human beings. The Game, The Rules, Why Men Love Bitches…people are drawn to these books to help them puzzle out the mysteries of the user interfaces on these strange, otherworldly things that the can’t understand but nevertheless feel like they need. And from my perspective, it all feels more than a little fucked up.

Now, we don’t talk about it directly, oh no. We pretend that objectification is bad–the notion that objectification is wrong is writ into most of the arguments against pornography, for example–yet at the same time we are strongly conditioned to do the most objectification right where it’s closest to home, in our own romantic relationships. “I am in this relationship because I have needs. It is my partner’s job to meet those needs. A partner who doesn’t fulfill my needs is as useless as a broken toaster.”

This happens to some extent in a wide variety of interpersonal relationships, but it seems especially acute in romantic relationships. If we need to go bowling and for whatever reason our friend isn’t available, that isn’t likely to get the same kind of response that we might have if we need something from a partner and the partner isn’t available. For whatever reason, it seems that we are socially more predisposed to see our friends as fully and individually human than we are our partners.

In polyamorous relationships, the extent to which many folks seem to want to give their partners any measure of freedom only in direct proportion to how quickly we can yank the leash back if they aren’t doing their job fulfilling our needs. I’ve seen people place all sorts of limits on their partners’ behavior that seem calculated to make sure that all these external, secondary relationships do not ever impinge on our partner’s utility as a need fulfillment machine; the instant some external relationship comes between one’s need and the ability of one’s partner to fill that need immediately, look out.

I call this the Magic Genital Effect–the notion that sex changes the game in such a way that the person we’re having sex with is somehow less human, less deserving of autonomy, less able to negotiate around complexities, or otherwise less worthy of being treated as an individual human being an someone whose genitals we aren’t rubbing.

I recently saw a brilliant example of the Magic Genital Effect in a poly forum I sometimes read. A person in that forum argued that a big problem with polyamory is that the secondary will eventually want to be recognized as an equal partner, and that’s bad because it might cause disruption in the “primary couple” and in the primary couple’s social circle if they have friends who aren’t poly. He argued that an existing couple has a history together, and anything that might cause disruption to that is bad and must be avoided.

I recently saw a brilliant example of the Magic Genital Effect in a poly forum I sometimes read. A person in that forum argued that a big problem with polyamory is that the secondary will eventually want to be recognized as an equal partner, and that’s bad because it might cause disruption in the “primary couple” and in the primary couple’s social circle if they have friends who aren’t poly. He argued that an existing couple has a history together, and anything that might cause disruption to that is bad and must be avoided.

My take on that is that disruption is a part of life. Nobody ever has a relationship in which everything works with 100% smoothness 100% of the time. There are many, many stressors that can cause disruption in a relationship: losing a job, moving, being promoted, an illness or accident, anything. We develop skills for dealing with disruption, we talk about things when we feel out of kilter, we work together with our partner to get through difficulties or changes in the relationship–this is what makes a partnership.

And I asked the question, would you feel that it was bad for a couple who had a child to have another? After all, the existing child already has a history; the arrival of a new child can and quite likely will cause disruption. Things will change. Dynamics will shift. The old way will be disrupted. Why is that bad? What would we think of someone who says you should never have two children because it might disrupt things for the first child?

The answer, perhaps predictably, was “Primary and Secondary lovers cannot be compared to first born, second born because the love shared is not the same.”

This is fascinating to me. It’s the Magic Genitals Effect writ large; changes in one’s family life are not the same if we aren’t rubbing genitals. The notion that we might change the family dynamic and trust that we can deal with, work through, and communicate about disruption that occurs is totally taken off the table as soon as the genitals come out.

This goes back to the idea of partners as need fulfillment machines, I think. What makes the genitals special? We tend, rightly or wrongly, to think of rubbing genitals in the context of romantic relationships. Why do we assume that disruption is automatically bad in cases that involve genital-rubbing than in cases that don’t? Because the genital-rubbing part is one of the key pieces of seeing a partner as a machine for fulfilling our needs. In addition to their other utility in serving other needs, our partners are primarily objects for meeting our sexual needs, and if they aren’t doing that (for whatever reason) they are broken. Something is wrong. You don’t negotiate with your toaster if it isn’t toasting bread correctly; it would be absurd even to think that you and your toaster have a relationship in which a disruption in toast-making is something that you each work through through mutual conversation. Why does the “but that’s different” argument work when the magic genitals come out? Because we tend, I think, to be predisposed to seeing sex partners as need fulfillment machines, and to believe that if they aren’t filling our needs, they’re doing something wrong.

That’s the problem, at least as I see it. I’m not sure what the solution is.